Viewpoint: Life in a blind boarding school

- Published

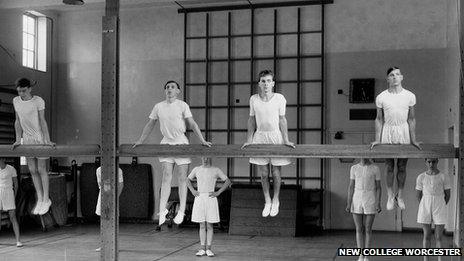

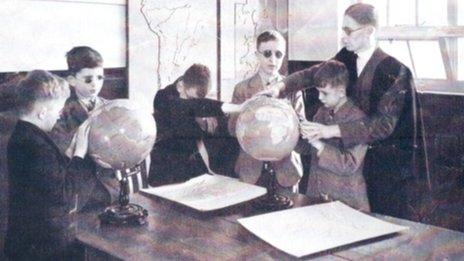

In the past PE lessons were quite regimented

Peter White had a love-hate relationship with the blind boarding school he attended, but what is it like today?

New College is a residential school for blind and partially sighted children just outside Worcester. It is where, back in the late 1950s, I spent the years 11-18, and it is where I have been frequently returning over the past year to meet the latest generation of 11 and 12-year-olds to enter the school.

How has it changed? How different are the teaching, the technology and the expectations of the children who go there?

The idea of "special" schools has pretty much gone out of fashion. In my day going to what would have been known as "the blind school" was really the only option. It was not until the late 1960s that the odd rebellious parent started to press to send their visually impaired child to the local mainstream school.

Many disabled people who went through what they see now as "segregated" schools are now indignant that it was thought right to separate them from the rest of society for their education, and words like "integration" and "inclusion" have taken on an almost sacred significance.

It is also true to say that quite a high number of visually impaired children do attend their local schools, and some do very well.

Local authorities are often now unwilling to send children to residential schools "out of county", when they believe they have adequate facilities of their own, and are conscious of squeezed budgets. And yet New College, Worcester, as it is now known, is still fighting for its survival.

In the autumn of 2011, 19 new pupils started at the school - the total is still under 100 - seven of them as first years. And it is them I have been following. All of them had been educated in mainstream primary schools, so why have they given up the comforts of home to board?

As he packed his case for his first term, 11-year-old Rufus put it pretty succinctly.

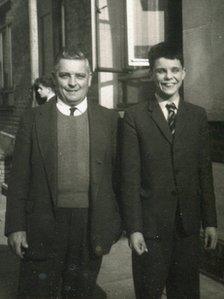

Peter and his dad as he started school at Worcester

"I've been blind from birth, and I just want to make friends with people of my own type, who are blind too, who write and read in the same way as I do."

It is clear he has had quite a say in the decision. His mother originally hated the idea of her boy going away, but when he returned from a trial few days at the school saying he had loved it, she bowed to the inevitable.

She had also begun to suspect that when it came to specialist help with braille, computers with synthetic speech and acquiring day-to-day living skills, he might be better off.

For Angel, there was an even more pressing reason for wanting to go to Worcester.

"I hope I'm not going to be singled out, because I've had that all my life. They kept calling me names because of my sight, they took things off me. I told the teacher, but they didn't listen."

Worcester is a very different place. This is not so much the academic side - yes, they use computers where I had a wonderfully old-fashioned braille machine, but they still do the core subjects we would have done, and university is still the expectation for most, if not all of these youngsters.

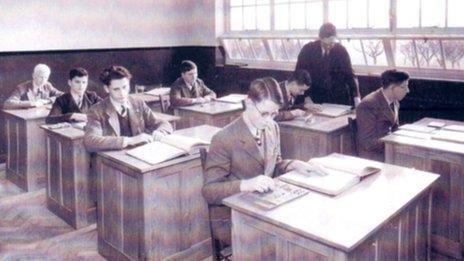

Established in 1866, Worcester College for the Blind gave boys the opportunity to progress to higher education

There was no equivalent to Worcester for girls until the National Institute for the Blind - as the RNIB then was - set up Chorleywood College, Herts, in 1921

In 1936, the National Institute for the Blind also took financial responsibility for Worcester

In 1987, Worcester and Chorleywood merged on the site of the former - 20 years later, the college became independent as New College Worcester

But the really striking differences are about lifestyle. When I went to Worcester, it was run on the lines of an old-fashioned public school. We had very little private space, slept eight or 10 to a dormitory, and discipline was largely left to older boys. The term "pastoral care" never passed anyone's lips, to my knowledge.

Staff were chosen for their academic prowess, not for the softness of their shoulder to cry on. I even had a brother at the school, which should have made it easier, except I never saw him. When I first got to the school he would say, "You all right?" And I'd say, "Yeah," because we were boys and tried not to show any emotion.

The most crucial difference is gender. In my day, it was all boys. New College now is co-ed and the youngsters live in houses run by the equivalent of housefathers and mothers. Some pupils have rooms of their own, or at most they share with one other.

Paul Diamond is a housefather at the school, in charge of one of the houses which are designed to feel more like home than school. Paul was a pupil when I was there, although he came late to the school after losing his sight in an accident. He subsequently taught at the school and remembers when it became a mixed co-ed in 1987.

"I thought it transformed the place into a much more realistic microcosm of society, because there were girls around you know, and they were these sort of strange, remote creatures, except for a Tuesday night when we had ballroom dancing lessons," says Diamond.

There is another big difference from my time there - pupils now learn life skills. They are expected to make their beds, keep their space tidy, but they also learn to cook, do the washing up, and look after their clothes. You feel if there were a problem, there would be someone to go to, and not necessarily just a teacher if you felt you needed someone more neutral.

The children almost all have mobile phones, and can phone home more or less when they like.

There is much to admire in the new version of Worcester College, and much I think I would have enjoyed, though I did sometimes catch myself wondering whether the children had lost some of the independence that we enjoyed.

We certainly had more freedom, indeed, we were expected to go out on our own, despite having no formal training with a white cane or a dog. This could explain why, a year into my stay at Worcester, I strayed into the path of a lorry not far from the school.

It is a sign of those times that a few days later my parents received a terse note to say that Peter had had "a slight brush with a lorry", but that he was "all right now". No writs, no lawyers, and despite the accident, things went on much as before.

Perhaps you can take "sink or swim" just a bit too far, although I still feel that I and my friends owe our robust attitude to life and the competitive world in which we find ourselves to the school's formerly laissez-faire regime.

But I am sure the parents of the new intake at New College might not necessarily agree with me.