Hillary Clinton: A long journey

- Published

Over the decades, Hillary Clinton has gone from student activist to globetrotting stateswoman. On her last day as US secretary of state, has her journey ended or is there more to come?

She's been on the world stage since Bill Clinton became the "comeback kid" and she became first lady in 1992.

Americans have named her the most admired woman in the world 17 times in a Gallup poll.

After travelling almost a million miles around the globe, she leaves her job as secretary of state with close to 70% approval ratings - higher than any outgoing secretary of state measured since 1948, with the exception of Colin Powell.

President Barack Obama has described her as one of the country's finest secretaries of state.

Although many have always admired her, she has had many detractors and her approval ratings have occasionally plummeted over the course of her career.

Clinton, the first lady, was seen by her conservative opponents as uncompromising, confrontational and deeply polarising. They hated her and everything she stood for, and she hated them back, calling them a vast right-wing conspiracy.

"As first lady she was unapologetically political," says Jason Horowitz, a Washington Post reporter who covered Clinton's 2008 campaign for the Democratic nomination.

She was the first wife of an American president since Eleanor Roosevelt who played a prominent role in policy-making. She had her own office in the West Wing, a degree and a career, and critics accused her of trying to be co-president. Her efforts at healthcare reform faced a groundswell of opposition and failed.

When she decided to run for president, "a lot of people thought she did not stand for what America was supposed to stand for", says Horowitz.

"But I don't think there was one underlying thing all those people felt about her. There are these empty vessels that people pour into. She's one of those people that people project on to."

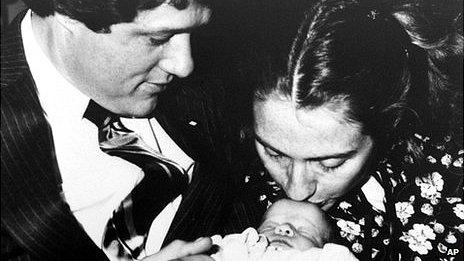

Born Hillary Diane Rodham in Chicago, Illinois, in October 1947, she attended local schools before graduating from Wellesley College and Yale Law School, where she met Bill Clinton.

She moved to Arkansas in 1974, marrying Bill a year later, and was made assistant professor at University of Arkansas School of Law. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter appointed her to the board of the Legal Services Corporation.

During 12 years as Arkansas' First Lady, Mrs Clinton worked for the Children's Defense Fund and co-founded Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families. The couple's daughter, Chelsea, was born in 1980.

In October 1991, Bill Clinton announced his intention to run for president at a rally in Little Rock, Arkansas - applauded by Hillary, their daughter Chelsea and his brother Roger.

After her husband's election as president in 1992, Mrs Clinton led successful bipartisan efforts to improve the adoption and foster care systems, reduce teen pregnancy, and provide insurance-based healthcare to millions of children.

She had already stuck by Bill when his affair with Gennifer Flowers emerged in 1992. And the family again came under strain during his second term, when the president admitted an "improper relationship" with intern Monica Lewinsky.

In 2000, she made history as a first lady by getting elected as New York senator. She continued to campaign for more affordable healthcare and won re-election in 2006.

In 2008, Clinton announced she would try to make history again - bidding to become the first female US president. However, she would narrowly lose a hard-fought battle with her rival for the Democratic nomination, Barack Obama.

President Obama declined to choose her as his running mate - instead opting for Joe Biden - but did select her as secretary of state. She became a key figure on the international stage.

Clinton also had a difficult relationship with the media during her White House years, which continued on the campaign trail. Horowitz recalls a particularly low time in 2008. Hoping to ease the tension, Clinton came into the press bus to pass around doughnuts. But no-one responded to her peace offering and the doughnuts were left untouched.

But the first lady-turned-senator also had legions of fans. Liberals loved her, women's rights advocates in the US and abroad saw her as a trailblazer. So by the time she began her own run at the presidency in 2008, she was the clear frontrunner for the Democratic nomination.

Her strategists still agonised over how to present her to the public. They decided to make her look tough.

"She was the first woman with a real clear shot at becoming president of the US and there was a feeling in her campaign by some of her advisers that she always had to project strength," says Horowitz.

Clinton's advisers didn't want her to seem overly motherly or warm. But in the end, the strategy worked against her. She often came across as too harsh and cold and, according to some, disingenuous.

She contrasted with the rising star of the race. With his life story, his oratorical skills and charisma, Senator Barack Obama fired up the crowds. The fight for the nomination, bruising and nasty, went on for months. Clinton's main charge was that Obama was not ready to be commander-in-chief. Obama said that Clinton's only foreign policy experience was sipping tea with world leaders.

Asked during a debate why she was having trouble getting voters to like her, while they seemed to like her rival, Clinton laughed and said that while she liked Obama, she didn't think she was that bad. Standing next to her, Obama retorted dryly: "You're likeable enough, Hillary." It was just one of the many moments that laid bare the tension between the candidates.

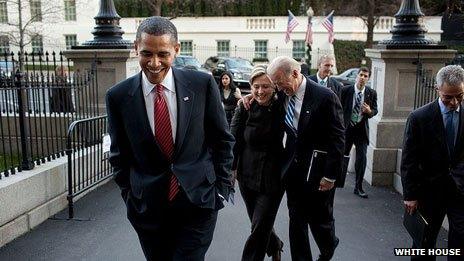

When Obama ultimately, and narrowly, won the nomination, the rivals made peace.

Clinton even campaigned for Obama, bringing the 18 million votes she had won in the primaries along with her. Clinton had done well not just with women but also working-class voters and the elderly. But President Obama surprised everybody - including Clinton - when he picked her as secretary of state.

Clinton needed some convincing but she eventually said yes. In public she always said she felt one couldn't say no to the president if he asked you to serve.

Hillary Clinton speaks to the BBC's Kim Ghattas about her time as Secretary of State

She also wondered how she would have felt if she had won and he had rejected her request to serve. But was there any bitterness in private?

"Never. Never once. I think she's a professional," says Lissa Muscatine, a friend who has worked with her at the White House and at the state department.

"She's been in this business a long time, she's had ups and downs and I think she is one of these people who is forward thinking: 'OK, what's next? I'm going to start working on what's next because that's a positive thing I can do. I'm not going to dwell on the past.' Others might have crawled into bed and pulled the covers over them."

If this sounds unemotional, Muscatine says Clinton is simply very pragmatic, a trait that allowed her to work with people in the Senate who had sought to impeach her husband.

As a first lady, Clinton had travelled overseas extensively, becoming a world figure and building ties with presidents, prime ministers and monarchs. So in her first few weeks at the state department, foreign leaders flocked to Washington, eager to shake hands with America's new ambassador to the world.

"Madame Secretary, on a personal note, I hope you know the admiration and respect with which you are held in the United Kingdom," said David Miliband, the then British Foreign Secretary, as he met Clinton during her first week at work.

His words exemplified how many around the world saw Hillary Clinton. "For many years," Miliband continued, "you have not just been an ambassador of America - you've been an ambassador for America and everything good that it stands for in the world."

Four years on, Miliband still remembers Clinton's debut at an international event.

"I will never forget the first Nato meeting that she arrived at in Brussels. I'd arrived an hour before her and there were a few people in the entryway. Suddenly there were thousands of people craning to get a view of her and that's where my understanding that she was a rock star came through very, very strongly."

But when Obama picked Clinton for his team, he knew he was getting much more than a performer with star status.

"Now we all take for granted that it was a good idea," says Philippe Reines, one of Clinton's top aides. "But go back to 2008 and it was shocking to all - to her, to everybody but one person.

"President Obama chose her for lots of reasons, but also because he knew what he was inheriting as president. The previous eight years were not a golden age of diplomacy. He knew that she was the best person to restore America's standing."

There was indeed much restoring to be done. After the Bush years, with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, with rendition and waterboarding, America's reputation around the world had taken a battering and its standing as the world's sole superpower was in doubt.

The Obama administration wanted to change the substance and tone of American foreign policy. So Clinton embarked on a new campaign, for the US itself. She wanted to reach out directly to people, in all the countries she visited, to repair her own country's image.

Day one at the state department

Easy to do with adoring crowds in Europe, but a much more daring move in places where the US is widely despised, such as Pakistan. Clinton had been there as first lady and returned in October 2009 as secretary of state.

"Going into the trip she said: 'I don't want to resign myself to giving up on trying to change people's minds,'" says Reines.

"We said: 'It's not going to be pretty.' And she said: 'I want you to load it up and I want you to make me a punching bag.' Because once you let people express their frustrations, they also realise it's an opportunity to express their desires and their own goals for their nation and how the United States plays a part in that."

I was on the trip as Clinton sat through endless media interviews, town hall gatherings with students and meetings with tribal leaders. The tone was acerbic and angry. I could see her staff shrinking in their chairs while their boss got pounded but remained calm, responding with warmth, empathy but also firmness. Even though no single trip or charm offensive can erase decades of distrust, it was obvious that by the time she left three days later, the media coverage had softened.

But better PR, of course, is not enough on its own, especially when the use of US drones in Pakistan - and the raid to kill Osama Bin Laden - pushed relations to the limit.

"Pakistan-US relations went through the worst time during Clinton's tenure as secretary of state," says Pakistan Foreign Minister Hina Rabbani Khar. "When you come out of the worst times, I must give her a lot of credit for the wisdom she showed."

When Pakistani soldiers were killed by mistake in a Nato strike in November 2011, the relationship broke down - Pakistan refused to help the US with anything until it got an apology. Clinton quietly pressed the White House. In the spring, Washington finally offered a carefully worded apology.

"If the US was a country that was not willing to say sorry for the loss of 24 lives, no matter what the circumstances, that's not the image the US wants and she completely understood that," says Khar. No-one could handle "the long-term repercussions of allowing ourselves to drift further away. She came to the job with a lot of history, a lot of understanding as first lady and senator."

With former UK Foreign Secretary David Miliband

Clinton also gets praise from Republicans, such as former presidential candidate and Senator John McCain, who came to respect her during their time in the US Senate together.

"I think she has established relationships with leaders of well over 100 nations, so she can pick up the phone at any time," he says. It's a rapport that helped defuse many crises, he adds.

One critic of the administration says Clinton's ability to press the flesh made her the perfect foil to the more aloof Obama.

"He doesn't seem to have enjoyed cuddling up to foreign leaders. Some presidents do and some don't. He doesn't seem to like it. He has therefore left the care and feeding of foreign leaders to her," says Elliot Abrams, who was deputy national security adviser during the Bush administration.

"Meeting after meeting, trip after trip, hour after hour she's done. Someone's got to do it because these personal relationships are important and that's been a great service to the administration and to the country."

Over four years, Clinton travelled close to a million air miles - that's almost 40 times around the globe.

Her predecessor Condoleezza Rice did reach the million-mile mark but Clinton visited more countries than any other secretary of state, trying to bring American diplomacy to places such as the Cook Islands, seemingly inconsequential but playing its own part in the US's Asia policy.

With Burmese democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi

Clinton's energy was endless on the road - she could plough through a dozen or more events during the day, barely stopping to eat, while her staff fell asleep in meetings or events. As a member of the press corps that travels around the world with Clinton, I found her energy frustrating as I tried to keep up, following her for 300,000 miles to 40 countries - and I'm roughly half her age.

But her goal as secretary of state was much more ambitious than making friends - she and Obama wanted to redefine the exercise of US power and leadership.

From day one on the job, Clinton spoke of the need to apply the concept of so-called smart power, using "the full range of tools at our disposal - diplomatic, economic, military, political, legal and cultural - picking the right tool, or combination of tools, for each situation", as she put it.

Clinton made women's rights a priority, appointing a permanent ambassador for women's issues, and she focused on development issues such as global food security, climate change and entrepreneurship programmes. But she also broke down traditional barriers and mistrust between the state department and the Pentagon, working closely with Defence Secretary Bob Gates and his successor Leon Panetta. One of the many whirlwind trips with Clinton took us from Pakistan to Afghanistan, Vietnam and South Korea, where she visited the demilitarised zone along with the border with North Korea in the company of Gates for a display of soft and hard power.

Asia is one area where the smart power approach has paid off - a delicate balance between diplomacy, military ties with allies and support for reforms and reformers such as Burma's Nobel Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi.

Clinton, a long-time advocate of human and women's rights and once a student activist, was excoriated at the start of her tenure for not focusing more on human rights in the relationship with China, but she rejected the criticism. In her view, the US couldn't talk only about human rights with its banker. The relationship had to be more comprehensive.

The test came when Chinese dissident Chen Guangcheng sought refuge in the US embassy in Beijing in the spring of 2012. The diplomatic crisis erupted just as Clinton was heading to Beijing for strategic and economic cabinet-level talks. The talks continued uninterrupted while tense negotiations about Chen's fate took place. Clinton eventually negotiated his departure to the US.

"We wanted to manage the entire episode in a way that showed the pragmatism and maturity of the China-US relationship," says Jake Sullivan, Clinton's deputy chief of staff.

"How can we on the one hand make sure we are doing right by who we are, and on the other hand build a stronger partnership and relationship with an emerging power? But there were certainly some harrowing moments along the way."

But repositioning the US for the 21st Century is a work in progress, and events always overtake plans and strategies. In January 2011, years of pent-up anger and frustration erupted across North Africa and the Middle East. Clinton had just warned Arab leaders that the region was sinking in the sand, but she didn't expect months of revolution and war.

On 25 January, just as the revolution was getting under way, Clinton said that "our assessment is that the Egyptian government is stable and is looking for ways to respond to the legitimate needs and interests of the Egyptian people".

But within three weeks, President Hosni Mubarak was gone, after 30 years in power. Egypt's modern pharaoh turned out not to be so stable. To this day, Egypt's revolutionaries, as well as proponents of forceful US action in Washington, have not forgotten that statement.

"I think the administration was slow on Mubarak and she was slow to realise that [Syrian president] Bashar al-Assad was just a butcher," says Eliot Abrams, who believes Clinton has had no impact as secretary of state.

"I think in Libya we were slow and then we went in and then we pulled out some aircraft, leaving the French and the British there. So I don't think she's going to come out too well on that."

Her destinations range from Libya...

The uprising in Bahrain is another black spot on the administration's record in the Middle East, one of the situations where - unlike in the Chen Guangcheng affair - the US found it hard to balance its interests and values.

Bahrainis demonstrating against the monarchy also feel bitter about the lack of support they received from Washington as they faced a brutal crackdown by the authorities. Bahrain is home to the US 5th Fleet, and Washington sees the small kingdom as a part of its efforts to push back against Iran in the region - interests trumped values here.

In Syria, the US did call for Assad to step down in the summer of 2012, but months later, he is still in power and the violence is tearing the country apart. Critics say this is a time for the superpower to be more decisive and get more involved, even militarily.

"I think it's the president's decision and the national security adviser much more than it is Secretary Clinton's, and it's a shameful chapter in American history," says McCain.

"We have let 60,000 people now be slaughtered, raped, murdered and tortured. Arms flow in from Russia and Iran [to Assad] and we sit by and watch. It's shameful.

"I think she influences the president on a great variety of issues. On this issue there have been others such as his national security adviser [Tom] Donilon who have played a much greater role."

Occasionally one senses frustration at the state department with the White House's reluctance to get involved in Syria in any decisive way - first because 2012 was an election year and now because there are no good, clear options.

But Washington's allies in the region say US inaction is making things worse. The US may have over-learned the lessons from the Iraq war. President Obama is keen to wind down wars, not start new ones, and he has adopted a cautious foreign policy. But despite frustration, these allies still believe that multilateral diplomacy remains the tool of choice for this administration.

"Being the secretary of state of a global power sometimes seems to be easy because you are representing a global power, but it has its own difficulties," says Turkey's Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu.

"If you give an impression that you are imposing something on others - sometimes on your ally or others - it might be counterproductive. But what I observed and I admired in Secretary Clinton was acting together with other countries and using multilateralism as the instrument of resolving issues."

... to New Zealand on the opposite side of the globe

But for all the reaching out, does Clinton - does the US - have anything tangible to show for her four years as secretary of state?

Critics say the "reset" with Russia has malfunctioned while Iran is getting closer to a nuclear bomb. Clinton clearly decided not to risk her reputation trying to bang heads together in the thankless task of Middle East peacemaking. But Clinton and her aides say you need to look at the big picture.

"The single biggest thing she's leaving behind is having restored American leadership, America's capacity to sit at the centre of coalitions - of countries and other actors - that can solve the big problems of our time," says Jake Sullivan.

"I think that that is the kind of legacy that endures beyond a single agreement or a single diplomatic moment. It's about a much bigger enterprise that is American foreign policy."

Although the administration's critics say US power has waned under Obama, its allies argue that influence is measured differently in the 21st Century.

"I think that what Hillary Clinton's secretary of stateship has done is lay the foundations, set out the tramlines for a modern role for the world's superpower in a world where there are other veto powers," says Miliband, referring to rising powers such as Brazil and Turkey, who have or want more of a say in how the world is run.

"This is a different world order from the one her husband confronted in the 1990s."

While she pursued her campaign for America, Clinton's own image improved and her ratings soared.

As she let her hair down, shimmying on the dance floor in South Africa, swigging a beer in Cartagena or becoming the focus of an internet meme - a Tumblr imagining her text messages, external - she seemed to attain a status of cool that had always eluded her.

Texting again?

Clinton the stateswoman seemed more comfortable in her own skin than Clinton the presidential candidate, more mellow, and people like Jason Horowitz from the Washington Post say the world finally got to see the real Hillary.

Her friends disagree.

"I don't think she's changed at all except from becoming an older, wiser person and a more mature politician and public servant," says Lissa Muscatine. "I think she's appreciated now for what she's been all along. She has become more comfortable with her own public persona, she has less to prove."

For people like me, who did not follow Clinton closely before she became secretary of state, the truth seems to be somewhere in between. She came across as very guarded and careful during her first encounters with the state department press corps, but relaxed gradually as she emerged from the pressure of domestic politics and focused on world affairs, finding her feet in her new role and within the administration.

By the end of 2009, we were seeing her funny, mischievous side, as she told jokes or gossiped about the love lives of movie stars. During our travels, she was often surprisingly open (off the record) about conversations she'd had in her meetings with world leaders, briefing us on the plane as we travelled to our next destination.

During her years as secretary of state, Clinton also emerged fully from her husband's shadow, no longer Clinton number two, but Hillary Rodham Clinton.

The change in perception was perhaps best exemplified after Bill Clinton made a surprise appearance at the Golden Globe awards last month, and host Amy Poehler exclaimed: "Wow, what an exciting special guest. That was Hillary Clinton's husband."

The job of US ambassador to the world also transformed Hillary Clinton from politician to stateswoman. She remained above the political fray for four years, and it has paid off.

"She's done this incredible thing, moving from being the most divisive person in American politics to someone that Republicans like. That's an amazing feat," says Horowitz. But if she decides to return to politics, the partisan attacks would resume.

Clinton's last few months as secretary of state were overshadowed by tragedy and a bout of illness. In September, the US ambassador to Libya, Chris Stevens, with three other Americans, was killed in an attack against the US mission in Benghazi.

The episode became embroiled in the partisan politics of election season. When Clinton finally testified in front of Congress, in her last weeks as secretary of state, the criticism and the fawning was split along clear partisan lines.

Republican Senator Rand Paul said that if he had been president, he would have fired her because of the security failure. The session was a reminder of Clinton's strength - and passion for the fight - and she seemed to emerge from the grilling mostly unscathed.

A stomach virus, concussion and a blood clot recently just put her out of action for a month - a reminder of her age, and possible frailty, although Clinton says her doctors have assured her there will be no lingering consequences. Four years before the next election, everyone is already asking - will she run?

"In some ways I would like to see her run," says McCain. "She would be extremely formidable. If I had to wager today, I think it's very likely that she'll give it serious consideration and she will be urged to."

With John McCain at nomination hearings for her replacement, John Kerry

From across the pond, Miliband urges Clinton not to rush the decision. "If she decides to go for it she'd be fantastic and she'll get a huge amount of support."

Her friends are also hoping for another presidential run. "I really care about her so I want her to rest first, but I would not be unhappy if she ran," says Muscatine, who believes Bill Clinton wants her to run.

Clinton herself insists she is done with the high wire of politics, but she has not firmly closed the door on the idea.

She says her life has been serendipitous - she remains flexible and open to opportunities that present themselves to her and she doesn't shut the door to anything unless it's necessary. So it's likely that she simply has not made up her mind.

She will not have to announce a decision for at least two years, but she'll do nothing to undermine her chances in the meantime.

But first there will beaches and speeches, and Clinton's friends hope it'll be mostly beaches.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

- Published30 January 2013