Petraeus affair: Why the cult of the American general?

- Published

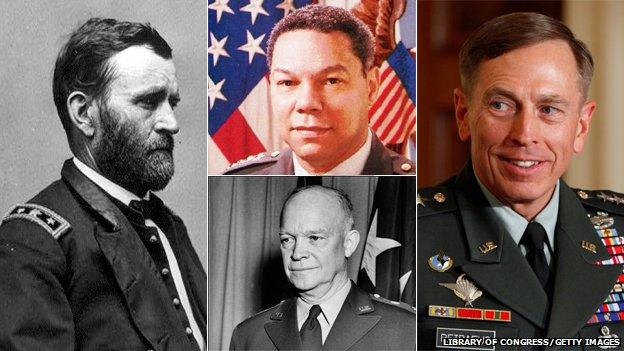

Famous American generals: Clockwise from left, Grant, Powell, Petraeus and Eisenhower

The downfall of retired Gen David Petraeus, once America's most prominent post-9/11 military leader, has stunned a nation. Why does the US hold its top military commanders in such high esteem - and what are the consequences?

America's 12th president was so apolitical that before he ran for the job in 1848 he had never voted.

But Zachary Taylor had been a successful general during the US-Mexican War. That was enough to take the Whig Party nomination - and win the White House.

"Generals have played a very central role in American politics - this cult of the general goes back to Washington and the Continental Army," says Ron Chernow, a biographer of George Washington.

"In Britain they get knighthoods. We reward them with political positions in high office."

Now, Gen Petraeus, the most prominent military leader in a generation, who went on to head the CIA and had been mentioned as a future presidential candidate, has wrought his own downfall in a dalliance with his biographer.

Gen John Allen, a Marine and Gen Petraeus' successor as commander in Afghanistan, has been accused of exchanging "inappropriate communications" with a second woman involved in the scandal.

Gen Petraeus' disgrace - in a matter that has little apparent connection to his performance as a military leader - opens the way for a needed public discussion, says Andrew Bacevich, visiting research fellow at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame, and a retired Army colonel.

"Knocking him off the pedestal - this huge standing that he had - ought to create a climate in which serious people can begin to ask serious questions about why our military has not delivered on our expectations" in Iraq and Afghanistan, he says.

America's adoration of its generals dates back to its founding years, when military leaders defended the country from the perceived twin threat of European invaders and Native American tribes.

George Washington, the first president, had commanded the army that won independence from Great Britain. At the time, Americans' sense of national identity was weak - they still considered themselves citizens of their respective states first.

Washington's army was one of the first national institutions, and he embodied it, says Chernow.

Petraeus seems to have been done in by his relationship with Paula Broadwell, his biographer

Since then, generals have exemplified much of what Americans profess to love - and distrust - about their democracy.

They are seen as having worked their way up through the ranks even from modest backgrounds. Gen Ulysses Grant, who commanded victorious Union armies in the Civil War and was later president, was the son of a tanner.

President Andrew Jackson was the son of Scots-Irish emigrants to the US. Before the White House, he was a general who won glory in the War of 1812 by defeating the British at the Battle of New Orleans.

"They earn their status on the basis of ability, and they get great public trust," says Richard Kohn, a military historian at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Even though they are adept at manoeuvring within military institutions, generals are seen as unsullied by national politics and its backroom deal-making or potential for moral compromise.

"Since fairly early in the history of the US, there's been a certain amount of cynicism toward politics on the part of many Americans," says James McPherson, a Princeton historian and author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Civil War history Battle Cry of Freedom.

Generals are perceived to be more pure - uncorrupted by the political cesspool, he says.

In the public eye, generals have an advantage over another prominent class of supposedly non-political politicians: business leaders.

"These are the ones who are supposed to be selfless," says H W Brands, a University of Texas historian and biographer of Gen Grant.

Gen Eisenhower was the last general to win the White House - in 1952

"They put their lives at risk for the welfare of the public."

And before the advent of mass media, military heroism lent instant fame in a far-flung country, says Chernow.

"How many Americans would have been so well known and admired throughout the country? Not very many," he says. "What an advantage for a military hero-turned-political figure."

America's adoration of its generals shows up in the numbers: 10 US presidents have served as generals. In the same period, a single retired general became British prime minister: the Duke of Wellington.

"In American politics you can parachute in at the top - you're a general," says Brands.

"In British politics, you have to work your way up through the party."

Like Taylor, Grant had no political background and before the Civil War was a failed businessman and junior army officer.

But the Republican Party saw advantage in his reputation and nominated him for president in 1868.

The Vietnam War was so toxic for the public that none of its generals found later political success, and their names are not etched in the American memory in the same way.

And like Vietnam, the Iraq war in which Gen Petraeus won national prominence was deeply divisive and regarded by many Americans as an imperialist exercise.

But since the 1970s, Americans have been adept at distinguishing the individual soldier - and his or her presumed heroism and gallantry - from the cause.

Few Americans look back on the Gulf War as a heroic national cause, but Gen Colin Powell was mentioned in the 1990s as a presidential candidate and later served as secretary of state. Gen Norman Schwarzkopf became a figure of international renown.

"Americans knock themselves out, especially since 9/11, praising the military," says Brands.

"If you put on the military uniform you're a prima facie hero. Generals are the epitome of that. They're the ones who have been most successful at the soldier's trade."

Today, the military is the most respected public institution in America. Seventy-eight per cent of Americans profess "a great deal" or "a lot" of confidence in the military, according to a 2011 Gallup poll, external.

Meanwhile, fewer and fewer political leaders today actually served in uniform, so they make up for that by genuflecting toward the military, says Kohn.

President Ronald Reagan began saying "we'll listen to the military", and George W Bush made a political mantra of "we'll listen to the commanders in the field", he says.

Gen Petraeus became a household name in January 2007, when Mr Bush named him overall commander of US forces in Iraq.

"Nothing in Iraq seemed to be going well, and there was this need to find somebody who could demonstrate that it was not a completely lost cause," says Bacevich.

"The moment was right for us to discover a new hero and Petraeus was that hero."

With Gen Petraeus' public downfall, the American public can begin to grapple with why after 11 years of war in Iraq and Afghanistan "we haven't won anything", Bacevich says.

The consequences of the myth of "the great heroic general" have been dire, he says.

"It's an excuse to not think seriously about war and to avoid examining the actual consequences of wars that we have chosen to engage."