Petraeus affair: Is this sex scandal different?

- Published

General David Petraeus has resigned as CIA chief after admitting an extramarital affair. So what are the rules governing modern-day sex scandals in politics and how does this one differ?

At first, the events that led to the resignation of David Petraeus sounded like a standard sex scandal. Petraeus, who held the top position in the CIA, stepped down after admitting an affair, which was later confirmed to be with Paula Broadwell, his married biographer.

But the story now includes a shirtless FBI agent, external and an "unpaid social liaison" who received threatening (or not-so-threatening) emails from Broadwell, and also exchanged supposedly flirty emails with another military bigwig, Gen John Allen.

It does not, however, seem to include much of a scandal - at least not where sex is concerned.

Any sense of outrage has seemed to focus more on what right the FBI has to search emails and computers, and how much privacy we civilians can expect when logging on to Gmail.

Sex scandals ain't what they used to be. In the years since Congress sought to impeach Bill Clinton for lying about his relationship with Monica Lewinsky, the public has become more understanding about what it will and what it won't accept, as far as sexual transgressions are concerned.

"I think that people's attitudes have changed and I think their rules for handling sex scandals have changed," says Juliet Williams, associate professer of gender studies at UCLA and co-editor of the book Public Affairs: Politics in the Age of Sex Scandals.

"Clinton established a certain type of archetypal response that we have seen adopted and adapted over time."

The Petraeus model is breaking the mould - but it also follows familiar territory. A look at three truisms from previous scandals, and whether Petraeus's story is any different.

1. Timing matters

A scandal has less chance of sinking you if the timing is right. Take Senator David Vitter. Vitter, a conservative, was found to be in the "black book" of a DC madam only a few months into his term. It made for big headlines - but Vitter wasn't up for election for three more years.

"That's enough time to make people forget about it," says Alison Dagnes, associate professor of political science at Shippensburg University.

When he did run for re-election, he won handily.

On the other hand, the Petraeus scandal's timing guaranteed maximum attention: breaking around the election and soon after the death of four Americans in Benghazi it was bound to look more suspicious - indeed, the story became public after the FBI agent who initially reported the threatening emails feared the investigation was being stalled for political reasons. (It wasn't).

2. Apologies beat denials

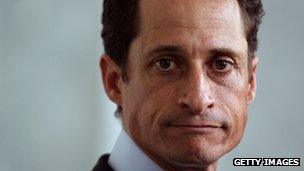

Anthony Weiner

Politicians like Anthony Weiner and John Edwards were sunk in part because they denied the rumours of their bad behaviour for so long, acting shocked - shocked! - that anyone could ever suggest such a thing. Eventually, they were exposed as liars. But those who come clean early tend to do better in the court of public opinion.

"Folks that have done the mea culpa, have stepped up early and said 'I made a mistake', they are not judged as harshly," says Robert Watson, professor of American studies and author of Affairs of State: The Untold History of Presidential Love, Sex and Scandal.

By offering a brief, direct apology well before the rest of the story's stranger details unfolded, Williams says Petraeus has added strategic heft to the traditional post-affair apology.

The gender studies lecturer says: "I think Petraeus has picked up this idea in the military of a pre-emptive strike. What you have here is the pre-emptive apology. He resigned so quickly there was no chance for anyone to call for his resignation, and public opinion has turned in his favour.

"There's now a slew of commentary that is in a very sympathetic register saying, 'Poor David Petraeus, such a tragedy that this small personal transgression has now run him out of office.' He wasn't run out of office, he suffered no sanctions, the FBI protected him, he resigned.

"Through this act of pre-emptive apology he's getting the sympathy as if he had been the subject of a witch hunt."

That sympathy came too late to save his career - but it could save his historical reputation.

3. Politics is a dirty business

Most sex scandals involve elected officials, and often a partisan fight, says Watson. But with Petraeus, the issue is less about political hypocrisy than professional competence.

"I always say Millard D Filmore was faithful to his wife. Franklin Roosevelt was not. Who do you want to be your president?" he says.

Because Petraeus was so successful - and because his role involved national security and warfare, not working the halls of Congress - some have questioned whether the Clinton-era rules of sex scandal should apply.

Should the private lives of public figures be dragged into the spotlight? Or should we go back to ignoring the sexual indiscretions of public figures?

"We would have gotten rid of Dwight Eisenhower right before D-Day," says Watson, who notes that General Eisenhower had an affair with his British driver. "Could you imagine if we used the standard today if we did back then?"

But, at least in America, we don't. Public figures are expected to uphold a higher standard - and are open for public criticism and ridicule if they don't. That, it's clear, is a rule that hasn't changed.