Who, What, Why: Who first called it a 'fiscal cliff'?

- Published

The phrase "fiscal cliff" is now part of the American lexicon, describing the looming deadline when tax cuts expire and spending cuts kick in. But where did the term come from and is the image a helpful one?

No sooner had President Barack Obama awoken from his election night victory rally than the media was discussing the next pressing issue sitting atop his in-tray.

The so-called fiscal cliff describes the automatic tax increases and spending cuts due to take effect on 1 January, a combination which economists say would push the US into recession - with global consequences.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates, external the economy would contract in 2013 by 0.5% and unemployment would rise to 9.1%.

But the White House and Congress are trying to agree a package of measures that would divert the country from the fiscal cliff. On Wednesday, the president repeated his call for increased taxes on high earners to be part of the solution.

The phrase "fiscal cliff" has quickly taken its place in the national conversation, but what are its origins?

Long before the fiscal cliff came the "fiscal precipice", says lexicographer Ben Zimmer, pointing to an editorial in the Chicago Tribune in 1893:

"The free silver shriekers are striving to tumble the United States over the same fiscal precipice."

"The metaphor of the precipice is clearly an ancient one," says Zimmer. "And the cliff metaphor works for the modern age because of the cliffhangers of Hollywood, while driving off the fiscal cliff brings up the image of Thelma and Louise."

The first known use of "fiscal cliff" is thought to be in 1957, he says, when it appeared in the property section of the New York Times, external. Written by Walter Stern, the article used the term to refer to people over-borrowing to buy their first home.

"To the prospective home owner wondering whether the purchase of a given house will push him over the fiscal cliff, probably the most difficult item to estimate is his future property tax."

In the 1970s and 80s, it was used to describe the precarious state of city, state and federal budgets, most notably in relation to New York City's brush with bankruptcy in 1975.

One of its first uses in the Obama era was by Senator Jim DeMint in 2008, speaking about the president's spending programme.

But it wasn't until Ben Bernanke, chairman of the Federal Reserve, used it in a speech to a congressional committee in February of this year, in reference to the events of 1 January 2013, that the phrase leapt into the mainstream.

So the metaphor has stuck but is it really a useful way of discussing a complex set of events?

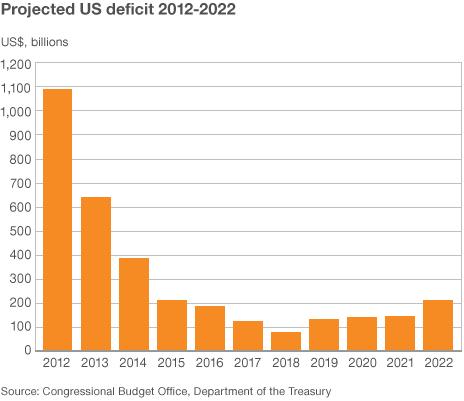

One aspect of the US economy which does go over the side of a cliff if Congress does nothing is the size of the country's budget deficit.

That visual image - of the deficit falling sharply like the gradient of a cliff face - only works if you look at the deficit over a decade, says Derek Thompson, business editor at The Atlantic. It is a more gradual fall if you look at the deficit on a week-to-week basis, he thinks, which is how negotiators in Congress are looking at it.

Thompson believes the cliff is a bad metaphor that is unhelpful to finding a solution to the crisis.

"You talk about a cliff, it's extremely sudden and the second you step off the edge you plunge to your death. But that's not going to happen once you step over the edge of the corner of 2012 and 2013. We're not going to fall off anything."

Taxes will go up so people take home less of their income, and Congress will have to find spending cuts divided between defence and non-defence, says Thompson.

"But nothing's going to change much in the first two weeks. It's more like a slope or a hill, if we're going with topographical metaphors."

A better image would be to think about dieting, he says. The US has been bingeing on spending and if you binge for too long you need to go on some sort of diet. A better expression would be a "fiscal fast", he says.

"There will be a short sharp recession in early to middle of next year, which is more like falling on your face after fasting too vigorously, and then the economy is going to grow."

The language is important, he says, because it can generate a panicked deal instead of the right deal.

Some Senate Democrats have begun to entertain the idea that going over the cliff would not be such a bad idea, because the tax increases would kick in and then could be cut for the middle class.

The Republicans don't want this to happen so the more perilous the prospect of the cliff-face, the more leverage for them, says Jonathan Chait of New York Magazine. "Republicans want to render that situation [doing nothing until January] unthinkable."

That political thinking, plus the memory of the debt ceiling crisis in 2011, external, are two reasons why there is such a confused view of the fiscal cliff, he says.

"The phrase has sparked a lot of poor thinking about the policy," he says. "Everyone is treating the fiscal cliff like it's a replay of the debt ceiling crisis. That was a situation where going over the deadline and catastrophe might ensue, with irreversible harm. So people were trained from that experience to think of this problem in those terms."

That's not the case now, because the economic damage facing the US is cumulative.

"It is the opposite of the debt ceiling, when the doomsday clock ticked down to a moment of sudden calamity. A full year of inaction would do a lot of damage, but a week, a month, or even a couple of months would not."

MSNBC presenter Chris Hayes renamed it 'fiscal curb'

But others believe any thought of going into the new year without a deal is dangerous.

"I can't imagine why anyone would want to take any risks with a recovery as weak as this one from a slump as deep as this one," says David Frum, former speechwriter for George W Bush.

Dismissing the notion that it suits Republicans to hype up the sense that the economy could go over a cliff, he adds: "Judging how much negotiating power President Obama has from a political point of view, he may have equal interests of under or overestimating it.

"The truth is we don't know how severe it will be, but the idea that 18 months after the debt ceiling we would experiment with politically-caused economic shocks just seems reckless."

Given the appetite from all sides for a deal before the new year, the probability is still high that the US will never find out whether the economy would really go hurtling over a cliff, fall down a hill or roll gently along a slope.

- Published2 January 2013

- Published26 November 2012