Carlos Acosta's Cuban ballet school dream

- Published

Ballet star Carlos Acosta has a dream of saving the ruins of an abandoned Cuban ballet school and starting a new non-profit academy for Cubans and fee-paying foreigners. But a dispute with the original architect threatens to kill the project.

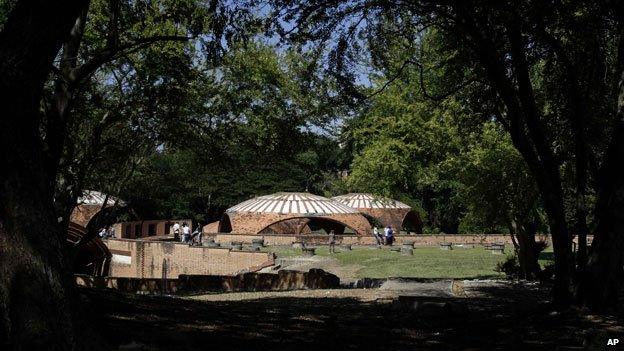

Discovering the ruins of Vittorio Garatti's Ballet School in Havana is like stumbling across a secret.

The extraordinary buildings are tucked behind tall trees, on the sprawling lawns of Cuba's Higher Institute of the Arts. Obscured from view are the interlocking domes covered in clay tiles, winding corridors and open sky-lights.

Now, almost five decades after the place was abandoned to the elements, Cuba's best-known ballet star has revealed plans to restore it and create his own dance school there.

"Just look at it - it's magnificent and it's in ruins. Someone has to do something," Carlos Acosta enthuses on a visit to the site.

Carlos Acosta shows Sarah Rainsford around the site of the ballet school

But the ballet school has been mired in controversy since its conception in the 1960s and this latest project is no exception.

The original architect, Vittorio Garatti - an Italian - is protesting that he has been sidelined. He has written to Cuba's Communist leaders claiming that Acosta wants to "appropriate" and "privatise" his building.

It was Fidel Castro who in 1961 called for the exclusive Havana Country Club and its manicured golf course to be replaced with the "best arts school in Latin America".

"The whole idea was typical of the early years of the revolution, when everything seemed new and possible and everyone was thinking on a big scale," explains Havana architect Mario Coyula.

The design, too, was ground-breaking, with five distinct schools, each one unusual. But as that early creative fervour faded into increasingly utilitarian tastes, work on the arts school complex was abandoned, deemed too "bourgeois".

The two completed schools began working, and the rest were left to the weeds.

"The schools were like a flag. If you were for them, you could be labelled a social elitist who only cared about beauty, not function," Mr Coyula recalls.

Many years later, Fidel Castro had a dramatic change of heart and called for the schools to be completed, but Cuba soon ran out of funds.

That is where Carlos Acosta is stepping in.

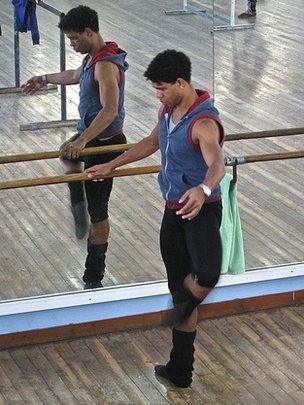

Acosta says he wants to help others achieve their dreams as dancers

Born and trained on the island, Acosta has been dancing abroad since his teens, most recently with the Royal Ballet in London.

Now nearing 40 and the end of a career in classical ballet, his mind has turned to the future, and retirement.

"What am I going to do? Go fishing?" he laughs.

"Cuba has always been in my heart, it pulls me. I feel a responsibility and I know I can help.

"I want to leave a legacy, something that benefits the next generation of artists. That really motivates me," he says, explaining that he wants to help others achieve their dreams as dancers.

His plan is to create a new model of school on the island that would be financially self-sustaining, run as a non-profit-making charity.

Details are still a work-in-progress but include only charging those who can afford to pay, and taking students from both Cuba and abroad.

Public performances in the main auditorium would be a key source of revenue.

It is not clear who will foot the large bill for widening and dredging the river that skirts the school, and floods on a regular basis.

But the cost of all other restoration work is estimated at around £6m ($9.5m).

The idea is to move in stages and raise funds along the way: so far, £200,000 has been pledged in donations from abroad.

"All the work here stopped again in 2008 with the hurricanes, just when we thought we were progressing," Art Institute Rector Rolando Gonzalez Patricio says.

"Sadly, we have not had the funds since then. We're talking about millions, when there are so many other priorities. I know Carlos is making a big effort and think we should be thankful for that," he says.

But even if fund-raising remains on track, the dispute with the school's original architect could yet stall - or even derail - the project.

The discord seems to stem from a misunderstanding of the role of British architect Norman Foster. He visited the Ballet School last year and his office conducted the site feasibility study for Acosta's team, without charge.

But Foster is not currently working on the restoration itself, although Carlos Acosta is clearly keen.

"Norman Foster, the great genius? Norman Foster in Cuba? Damn, yes!" he says, but adds that the architect's association with the project is currently symbolic.

"He legitimises the project and says, 'Yes, this building can be saved and I support that,'" the dancer says.

Still, Vittorio Garatti is clearly put-out.

"His major concern is that no other architect or engineer should destroy the school, or include something he would not admit," explains Miguel Barnet, a senior cultural official and friend of Garatti for many years.

"He doesn't want anyone to put their hands on his creation," he says.

That includes Carlos Acosta's plan to enlarge capacity in the auditorium and convert maths classrooms into dance studios.

Mr Garatti did not respond to emails requesting an interview with the BBC.

Carlos Acosta is frustrated.

"I understand - this is his [Garatti's] baby, the best thing he's every created.

"Hopefully we can solve our problems. The truth is that someone has to do something to rescue the place from the ruins," he says.

"Its been like this for decades," he points out, surrounded by brickwork sprouting weeds and coated in moss.

"I'm just trying to save it."