El Salvador gang truce: Can MS-13 and 18th Street keep the peace?

- Published

Inside El Salvador's Ciudad Barrios prison

In March this year El Salvador's most violent gangs - the Mara Salvatrucha and the 18th Street gang - agreed a truce. As a result, the murder rate of this small Central American country has plummeted - but can the peace last?

On a Sunday morning, the main street into Majucla, a poor community in the north of San Salvador, looks like any other. It is a dirt road, there are food stalls, and people walk up and down, many dressed for church.

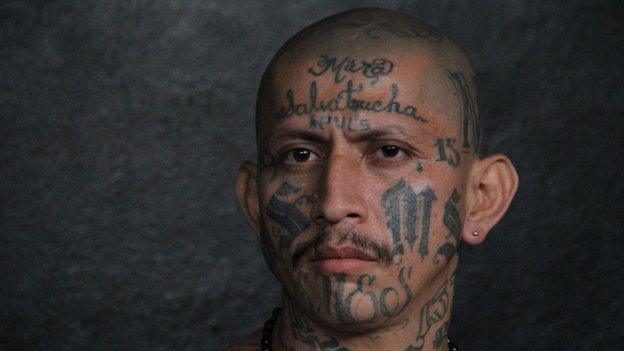

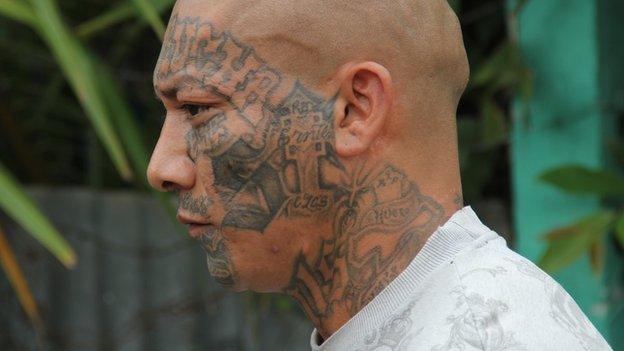

Some men stand around in groups of two or three, chatting - look closely and you will see the tattoos. One of them has artwork that starts on his skull, covers his face and neck and disappears under his T-shirt. On one cheek a large M is tattooed, on the other an S. All these men are members of the Mara Salvatrucha gang, known as the MS.

Until March this year, these men were at war with the 18th Street gang. Their deadly conflict pushed El Salvador's homicide rate to a high of 13 or 14 a day. Now the men with the tattoos - in communities like Majucla - bear responsibility for upholding a truce.

"The time is right, and we are showing the Salvadoran people we can be peaceful," says an emotional Ismael Guererro.

"I have lost too many friends and relatives in the violence. We don't want another war because we are thinking about our children."

Carlos Tiberio Valladares is an MS leader who says he is committed to the truce with rivals 18th Street

Mara Salvatrucha leaders in Cuidad Barrios prison meet to decide whether or not to speak to the BBC

A Mara Salvatrucha member from the community of Majucla in San Salvador

Mara Salvatrucha graffiti covers the walls of Majucla in San Salvador - the gang also goes by the names Mara, MS or MS-13

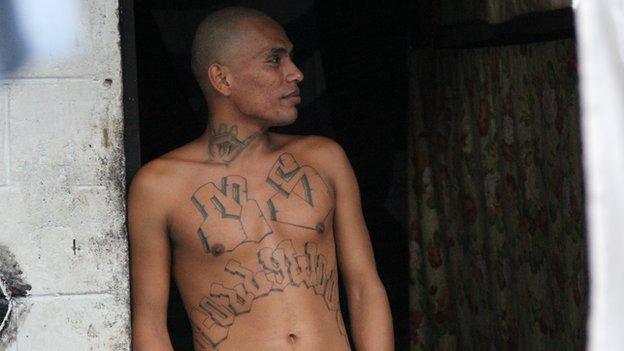

An 18th Street gang member at Cojutepeque prison in El Salvador. The prison was built to house around 300 inmates, but currently holds about 900 men

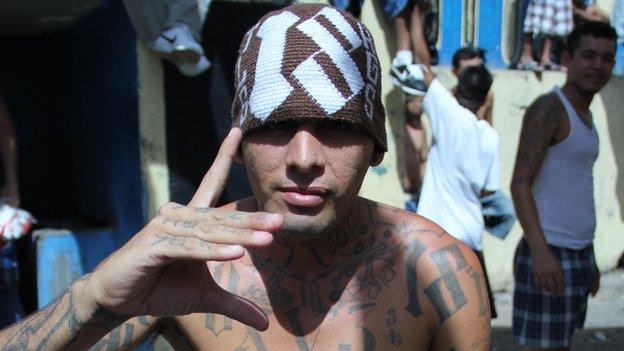

An 18th Street member shows the gang's sign in Cojutepeque prison

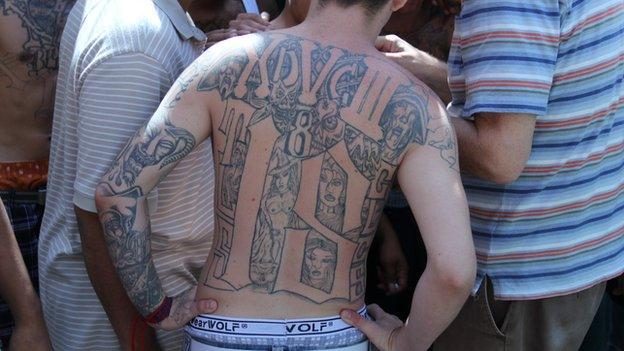

Many prisoners get their first gang tattoos while in prison as teenagers - this inmate has XV3 tattooed on his forehead and 666 on his chin (6+6+6 = 18) representing 18th Street

Ciudad Barrios prison only houses MS members, because of the deadly animosity with rivals 18th Street

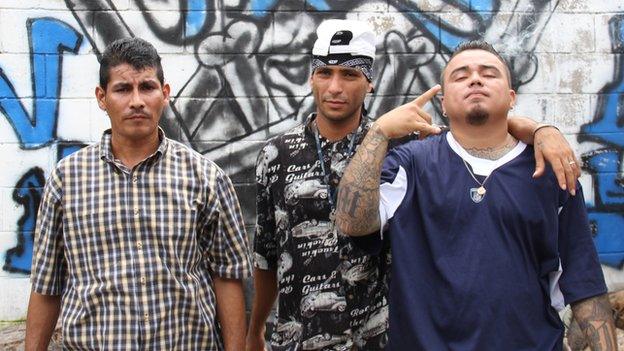

An 18th Street member shows his allegiance by making the gang's sign

MS member Dany Mendez spent six years in jail in connection with three murders. He is just 25 years old.

"Before the truce started we would go looking for our enemies - the 18th Street gang - to kill them," he says.

"I killed our enemies. Sometimes it was in self-defence, but that's part of life. And then the truce started. I think it's good to enjoy some peace and tranquillity - not just in neighbourhoods like ours, but in the whole country."

Mendez's sentiments are echoed by the leaders of his once-sworn enemies. At the prison of Cojutepeque, around 900 18th Street gang members occupy a jail built for 300 men.

Jose Heriberto Enriquez, who is serving time for murder, was one of the leaders who sat down in meetings with leaders from the Mara Salvatrucha.

"It was difficult," he remembers. "I mean, they see me in the street, they're going to kill me! So we had to agree that there would be mutual respect.

"We know they've killed a lot of our people. And I guess they feel the same way, because our 'homies' did the same thing to them.

"But in the end the main purpose of the truce was for us to stop the killings."

The agreement was negotiated in a series of secret meetings with both gangs' leaders in El Salvador's prisons.

It was facilitated by a Catholic bishop and a former rebel commander of the left-wing guerrillas - someone who battled the military in El Salvador's civil war in the 1980s.

The truce has been in place now for over eight months, and the murder rate has fallen to around five a day. It is a dramatic result.

The [FMLN] government of El Salvador insists it has "facilitated" not "negotiated" the truce.

The man generally believed to be the brains behind the strategy is the minister of justice and security, Gen David Munguia Payes.

"We found in research that more than 90% of murders were gang-related. So it was very simple - if we could get to the gangs we could control the killings," he explains.

"And it isn't just the killing of gang members that's diminished... Now the gangs aren't at war, they don't need to enforce recruitment in schools, so the number of students being murdered is down too," Gen Payes says.

In communities once dominated by bloody street battles, residents are now freer to go about their business. They can go out at night, send their children to the shops, and leave their front doors open.

But many Salvadorans are still suspicious. Some believe the gangs have been paid to participate in the truce - an allegation denied by the government and the gangs.

Others make more troubling claims - they believe local and Mexican drug cartels are somehow behind the peace. Gang warfare makes their business messy, and the traffickers need the truce to get their product north to the US market.

"The truce and the negotiations that made it are a strategy of drug-traffickers, not the government," says Father Antonio Lopez Tercero, a young Spanish priest who has worked in Mejicanos, a gang-dominated community in the capital San Salvador, for more than 10 years.

"The main problem in El Salvador and this region is not gang activity, it's 'narco-activity'."

Father Antonio organises beauty, hairdressing and computer repair courses for his parishioners - positive alternatives to gang life - and he is cynical about the fall in the murder rate.

"Of course there's been a drop - that's part of the strategy. It's what I call a 'mafia peace', that is, the end doesn't justify the means."

Gen Payes denies claims of drug cartel involvement in the truce.

"The gangs aren't involved in the heavy trafficking of drugs, although they are selling drugs locally," he says.

"But if we don't divert the gangs away from crime, with more than 60,000 members and the control they have, they could turn into cartels with arms, money and power.

"We must take advantage of this moment while gang members are showing a willingness to change."

But how well is the truce holding? For some Salvadorans it is a cruel fantasy.

Claudia - not her real name - has not seen her teenage son since he stepped out to buy some food one night in October.

She heard five shots. One young man was killed - his body lay in the street.

Claudia's son, who was associated with the 18th Street gang, disappeared. She thinks the Mara Salvatrucha kidnapped him.

"I think they wanted to torture him, that's why they took him away. And they probably buried him in one of their clandestine cemeteries that they have around the country. I know he's dead. I'm only hoping to find his body."

Disappearances like this put a question mark over the truce and they challenge the authority of the gangs' leaders - it is widely believed that those who violate the truce are themselves murdered.

In the prison of Ciudad Barrios more than 2,500 members of the Mara Salvatrucha are serving time in miserable conditions.

Since the truce, the most important MS leaders have been relocated here from the maximum security jail. Some of them - like their counterparts in the 18th Street gang - grew up in Los Angeles, refugees of El Salvador's civil war in the 1980s.

Then the US began deporting convicted felons - many of them gang members who were strangers to El Salvador. It is a policy that has contributed to the size and influence of gangs here.

Carlos Tiberio Valladares is a home-grown MS leader, serving 30 years for murder. He got his first tattoo at 16 - now his face is a canvas of blue ink. Many people would find him intimidating.

"But appearances are deceptive," he says. "What counts is what's in your heart."

Carlos wants to send a message to the people of El Salvador - especially those who are suspicious of what has happened with the gangs.

"We're committed to the truce. We're giving you our word and we won't betray that."

El Salvador is still holding its breath.

Hear the full report on Crossing Continents on BBC Radio 4 on Thursday, 22 November at 11:00 GMT and Monday, 26 November at 20:30 GMT. You can listen again via the Crossing Continents website or via the Crossing Continents podcast.