A Point of View: Pompeii's not-so-ancient Roman remains

- Published

Is Pompeii an ancient or a modern wonder? Its ruins have been rebuilt and the bodies of the volcano's victims are plaster casts, says classical historian Mary Beard.

Last weekend I spent a couple of hours with the remains of one of the human victims of the eruption of Vesuvius in AD79.

The corpse is apparently well preserved: a young woman, lying face down, shielding her face with her hands at the moment of death. Her dress has risen up and is tangled around her waist, her bare legs exposed beneath.

She is currently on display at the J Paul Getty Museum in Malibu, as the first exhibit in a show, external that explores the ways that modern artists - from Francesco Piranesi to Anthony Gormley - have responded to history's most famous volcanic eruption. "Welcome to Pompeii," she is meant to say. "The city of the dead".

I was curious to find out what visitors to the exhibition made of her. So I lurked and listened.

The kids were the most forthcoming. Many of them rushed up to her, then uttered some variant of "Oooh, uggh! Is that a real Roman?" Their mums and dads tended to improvise one of two fairly predictable responses:

"Yes dear, it is, but don't worry - she died a very long time ago"

or "No, don't be silly, it's just a model"

In an odd way, both those answers turn out to be right.

Ghoulish as they are, for most of us (me included), these bodies are always one of the highlights of any display of the discoveries from Pompeii (and a group of them will be starring in an upcoming exhibition at the British Museum, external). They number in the hundreds altogether, each one a casualty of the eruption.

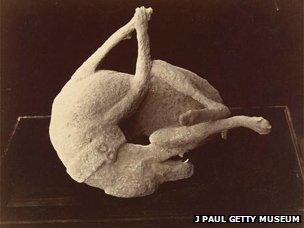

And they are not just human victims either. One of the most famous is the remains of a dog, still tied up, straining at its leash, in a futile attempt to make a run for it.

The truth is, though, that they are not actually bodies at all. They are the product of a clever bit of archaeological ingenuity, going back to the 1860s.

The early excavators had noticed, as they dug through the volcanic debris that covered Pompeii, a series of distinctive cavities in the lava, sometimes containing human bones.

The reason for that soon became clear. The material from the volcano had covered the bodies of the dead, setting hard and solid around them. As the flesh, internal organs and clothing gradually decomposed, a void was left - which was an exact negative imprint of the shape of the corpse at the point of death.

It wasn't long before one bright spark saw that if you poured plaster of Paris into that void, you got a plaster cast that was an exact replica of the body, but only a replica - more an "anti-body" than a real body.

And not just that - once the cast had been made, it could be used in turn to make more and more copies of the same person, rather like post-mortem cloning.

A 19th Century cast of a dog killed in the eruption

In fact, at the very moment that one version of the young woman is greeting visitors to the Getty Museum in Malibu, an identical version has pride of place in another Pompeii exhibition in Denver, Colorado - different casts and recasts of the same void made by the same dead human being 2,000 years ago (and 5,000 miles away).

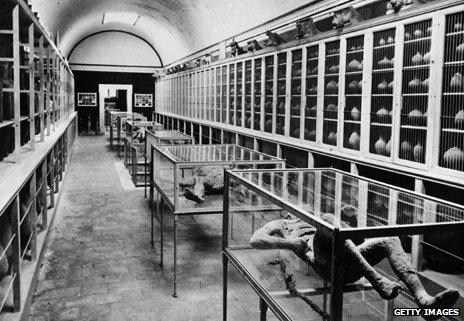

Bodies or anti-bodies, the re-creation of these ancient Romans in plaster caused a tremendous stir when it was first done in the mid-19th Century.

Family groups seemed to be brought back almost to life. Only the hardest of hearts remained unmoved at the sight of these doomed plaster people clinging to each other as catastrophe approached, mothers cradling their children, husbands embracing wives.

The clothes they were wearing also came as a shock. It was still generally believed in the 1860s that ancient Roman dress had been a skimpy affair, not merely suitable for warm Mediterranean climes, but flirtatiously flimsy and revealing too.

Concrete casts of the volcano's victims in Pompeii Museum, 1866

That idea faded almost instantly when the casts revealed that the victims were heavily clad, wrapped in cloaks and thick dresses, heads covered and some of them even in trousers. (Although I have never quite understood why those 19th Century historians were so certain that the garments people chose to wear in the middle of a volcanic eruption were a good guide to their usual day-to-day attire.)

But there are much wider issues at play than ancient Roman dress sense.

For a start, these strangely ambivalent objects bring us face to face with our own voyeurism. Why does it seem OK for us to gawp at these disaster victims, when it would be decidedly not OK to gawp at the death agonies of victims of a modern train crash or terror attack?

Is it because, as some parents at the Getty suggested to their kids, they are just so ancient that they don't matter to us in the same way? As if in becoming archaeological specimens they lost their right to human privacy? Or is it the simple fact that these are not Roman bodies that gives us licence to peer?

Surely, we don't imagine that a lump of 19th Century plaster poured into a void in the lava has any "right to privacy" - still less (as in the Getty example) a 20th Century copy of a 19th Century lump of plaster. As the other parents had it, they're "just models".

For me, though, these plaster victims prompt other thoughts too - about the city of Pompeii as a whole, and what it stands for. Partly that's because they are so eloquently trapped in that no man's land between the living and the dead, captured at the very moment when they lost their struggle against the fumes and lava.

Which is a bit like the city too. Is it really a vast tomb? Or is Pompeii a place where we can go to step back in time into the lives of the ancient Romans?

When they're not in disaster-movie mode, modern visitors like to think of its living side, with Roman bread still in the Roman oven and the trundling Roman carts - or the seedy encounters in the Roman brothel - only a glimpse away. Not so tourists 200 years ago, who found it the ideal place to reflect on their own mortality.

It was the novelist Sir Walter Scott, visiting the site shortly before his death, who first described Pompeii as the "city of the dead" - words he muttered constantly as he was carried round the excavations in a sedan chair.

But more than anything, it's the combination of the ancient and the modern - the 19th Century plaster combined with the fleeting traces of those real dead Romans - that stands so well for Pompeii itself.

Of course, there's no question that it is the best-preserved ancient town anywhere in the world, one of the very few places in the world where you can actually walk the Roman streets. But an awful lot of what you see there was built - or rebuilt - in the 20th Century.

Keen as they were to reflect on the transience of human existence, early visitors to the site were often decidedly disappointed with the place. It was, frankly, a wreck.

It looked, as one disgruntled tourist observed, as if it had been destroyed in enemy action. Well, of course it looked like that. It had been devastated by a violent volcanic eruption.

It wasn't until the houses began to be rebuilt and reroofed around 1900 that Pompeii became something like the ancient city we now visit - until, that is, the site was heavily bombarded by the Allies in World War II (in what really was enemy action, with more than 160 bombs dropped on the place). Parts of what we now see are a rebuild of a rebuild.

I'm not accusing anyone of "faking it". My point is that our Pompeii - like most classical sites, in fact - is the product of collaboration between modern rebuilders and conservators, and the original Roman builders themselves, with the lion's share of the work on our side.

And it's no less impressive or moving for that - as the body casts help to show.

One of the video clips played in the exhibition at the Getty Museum comes from Roberto Rossellini's film, Voyage in Italy, in which the lead couple, played by Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders, tour the country as their marriage disintegrates.

On their visit to Pompeii they watch the plaster being poured into a cavity left by two of the victims. In the movie's most haunting scene, these victims emerge as a couple tenderly embracing in their final moments - and a silent indictment of the hollowness of the relationship between Bergman and Sanders.

It might only be modern plaster poured into an ancient hole, but it still has emotional power, as the kids and their parents were finding, in their own ways, last weekend.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external