How to boost GDP stats by 60%

- Published

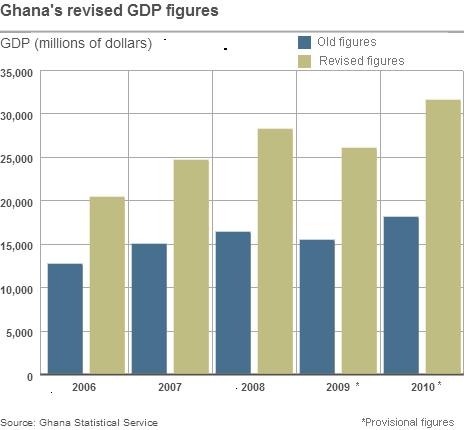

In 2010 Ghana announced a 60% increase in GDP estimates and Nigeria may soon follow suit. But how can the economies of these African countries seemingly grow overnight?

The answer is in the maths.

To calculate GDP in countries where data is sparse like Ghana or Nigeria, government agencies select a "base year" - a year when unusually good data on the economy is available. They then add on the extra data they collect each year to get a rough idea of economic growth.

In 2010 Ghana changed its base year from 1993 to 2006, and this led to a jump in GDP and the conclusion that, in previous estimates, about $13bn (£8bn) of economic activity had been missed. As a result, Ghana was upgraded from a low-income to a lower-middle-income country.

Nigeria is widely expected to announce a change in its base year from 1990 to 2008, although it won't be clear until the calculations are done what exactly this will do to GDP figures.

"When there are big structural changes in an economy the base year can quickly become outdated and that's exactly what happened in Ghana," says Todd Moss, development scholar and blogger at the Center for Global Development in Washington.

"The services sector basically exploded and the way they were calculating it they were assuming the services sector was still quite small so they were grossly underestimating Ghana's growth and economic activity."

Political interference was partly to blame for the slow rebasing of the Ghanaian economy. Until 2000 most institutions were not independent enough to be able to put out their own views and their own data, argues Sydney Casely Hayford, a business and financial analyst from Ghana.

Ghana finally rebased in 2010, in part because of pressure from the IMF and the World Bank.

But are the figures now reliable?

Sydney Casely Hayford, who has been studying the development of Ghana's economy over the last 10 years, says the GDP figure could still be out by between 10-20%.

"Until we are able to go in and do a proper quantification of the informal economy in this country it is uncertain exactly what degree of variation we have in our GDP figures.

"The figures are better but they are still wrong.

"We've settled into a particular lethargy. Now that we've been able to come to the 60% adjustment we've left it there and we are not looking to see how we can refine that and make sure that it is accurate consistently, so I think there is a little bit more work that can be done."

But what impact do poor statistics actually have?

Morten Jerven, author of Poor Numbers: How We Are Misled by African Development Statistics and What to Do about It, says they can have tangible consequences.

"These kinds of statistics are vital to international organisations and non-governmental organisations that for instance provide aid to Ghana. Now Ghana is a middle-income country it is according to that statistic not eligible for concessional lending from the World Bank for instance," he says.

Without accurate GDP figures we cannot make cross-country comparisons or rank countries convincingly.

Bicycle sales are one measure of economic activity

But GDP figures are not the only useful measure of economic activity, argues Todd Moss. Other indicators such as mobile phone ownership, the sale of bicycles or other consumer goods and even lights at night can all play a part.

So who is to blame for the bad statistics?

"In many countries the statistical office is like an orphan. I've encountered cases where the minister is not even aware that the statistical office is under his ministry," says Shanta Devarajan, The World Bank Chief Economist for Africa.

But, the revision of the figures seen in Ghana, and due soon in Nigeria, should be interpreted as good news overall says Devarajan.

"It is a sign of progress that we have more up-to-date statistics."

Listen to More or Less on BBC Radio 4 and the World Service, or download the free podcast.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external