After the Paralympics: Has anything changed for disabled people?

- Published

Three months after the Paralympics and positive attitudes towards disabled people have not faded, a survey suggests. But how much have the Games really changed things and do disabled people think the same way?

The legacy of the 2012 Paralympics was always going to be important.

Everyone knows a final push is necessary for disabled people to reach full equality in the UK with non-disabled people.

It's easy to find anecdotes from disabled people that show how the odds of daily life are still stacked against them.

Toilets are a classic gripe. Disabled blogger Lisa Egan recalls going into an accessible toilet where you would have to be standing and not of restricted growth to reach the toilet paper holder. "It's not rocket science to think that a disabled person on the toilet would need to reach toilet paper without having to stand up."

Then at a festival there was a toilet where the sink had a foot pedal to operate the taps. Not a massive amount of use to many wheelchair users.

Such anecdotes paint a picture of a world where carelessness makes life difficult for disabled people.

"Drive down any High Street in the country if you're an able-bodied person and look at it just for a moment from the disabled person's point of view," suggests disabled barrister John Horan who specialises in cases involving the Equality Act.

"Count the number of steps each shop has from the street. I guarantee that at least one in three shops would still make you go up or down and present a barrier to wheelchair users."

A big part of the change demanded by disabled people is about attitude.

Attitude could mean an employer accepting assistance animals in the workplace for people on the autistic spectrum because of the calming or dampening effect they have for their owner.

Despite some good legislation over the past four decades, disabled people are still not very visible in public life, and only 50% of disabled people of working age and who are willing to work, are in employment.

Against this backdrop, there were expectations for the Paralympics to provoke change.

Interest in watching the Paralympics turned out to be far higher than anyone anticipated with record TV viewing figures and sold-out Games venues. At the closing ceremony on 9 September, Lord Coe said: "In this country we will never think of sport the same way and we will never think of disability the same way."

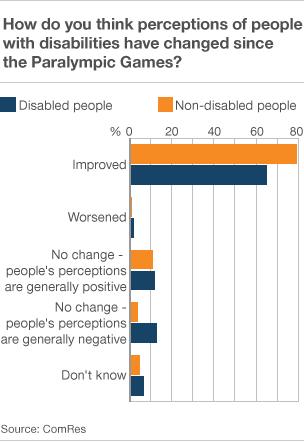

A BBC poll conducted by ComRes across the past three weeks suggests 79% of non-disabled people believe attitudes have changed towards disabled people since the Paralympic Games.

Campaigner Kaliya Franklin noticed an attitude shift on Twitter during the Paralympics opening ceremony. For fun, she pointed out the para athletes were "outrageously good looking" and introduced her own hashtag #paralympicperving. People joined in with her discussion.

"When they saw what I'd done, able-bodied people started tweeting me asking if they were allowed to comment on physical appearance like that. No one was looking at disability by the end of the night they were just looking at which countries had the hottest athletes."

This public ogling was a mile away from the rather earnest references to Paralympians as being "just like you and me" or as "superhuman" by mainstream media. They were attempting to be right-on positive in the run-up to the Games.

The new BBC/ComRes poll showed that 75% of non-disabled people said they themselves felt more positive about the role of disabled people in UK society since the Paralympic Games. The survey found 76% of disabled people agreed, suggesting that the Paralympics was equally inspiring to disabled people.

This is markedly different from the results of a Scope/ComRes internet poll conducted a year prior to the Paralympic Games which suggested that a fifth of disabled people thought the Paralympics made them feel second class. This poll was based on a smaller sample than the BBC poll and included parents and carers of disabled people.

Asked whether public attitude generally had changed since the games, the BBC poll found 79% of non-disabled people agreed. But only 65% of disabled people agreed with the proposition - showing lower confidence in those who have personal experience of the attitude being measured.

Franklin isn't surprised. She says that disabled people like her are on the receiving end of attitudes and so perceive them quite differently.

"We can't take it away from what's going on with the cuts and the economic situation," she says, alluding to the Work Capability Assessments first established in 2008 by the Labour government and now conducted for the coalition by Atos, where disabled people are called in for a one-to-one test of their ability to return to or begin work.

Franklin thinks the Paralympic upsurge and benefits situation are "intrinsically interlinked" in the minds of disabled people in the UK.

The campaigner attended the Paralympics in Stratford and contrasts the aura of the Games and the reality of everyday life.

"People had worked really hard to make the park and its events as accessible as possible. They'd made things much easier to get around and gamesmakers were there ready and waiting to help with smiles on their faces. Then we go back into reality where we realise it's not really like that."

On her return from the Games, four taxis refused to pick Franklin up, but a fifth taxi driver, who had seen this happen, apologised endlessly for what had happened to her. "I want to live in that magic Paralympic bubble world," says Franklin. "We showed as a country that we can have a very different attitude in terms of not just physical access and adaption but the way in which people interact and treat each other."

Richard Hawkes, from Scope, says the Paralympics effect shouldn't be written off.

"We need to build on the momentum. Let's ask what else we can do to increase disabled people's visibility in the media, in politics, in the arts and above all in everyday life."

Asking questions about legacy now may be a little too soon.

In October, Paralympian Baroness Tanni Grey-Thompson soberingly pointed to a tangible measurement of attitude.

"When we see next year's hate crime figures then we'll have a better view of whether there's been a real change or whether it's been a moment in time," she said.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external