Train hopping: Why do hobos risk their lives to ride the rails?

- Published

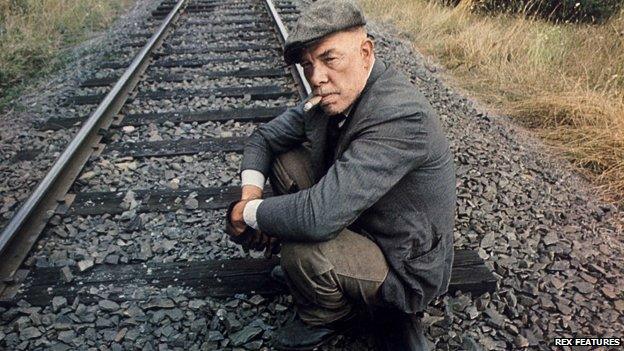

Lee Marvin played a hobo in the 1973 film Emperor of the North

Train hopping is a long-established tradition in the US, particularly popular in the Great Depression when the jobless took to the rails to find work. But why would people risk their lives hitching a ride on a freight train today?

Train hopping, sometimes referred to as freight hopping, is against the law in all US states. But the practice continues.

Homeless hobos, immigrant workers, mostly from South America, and thrill-seeking US citizens surreptitiously all hitch rides, despite the increased use of electronic surveillance and tightened security around rail yards.

"My name's Tuck. I rode the trains for like 25 years, man, 24 hours a day."

Tuck is one of those who went in search of work, and ended up seeing the world.

"I left home because I felt like I was just an extra mouth to feed. Because we was so poor I felt like a burden, so me and my oldest brother decided to leave.

"We started hitching and ended up in Odessa, Texas. In the oil-fields. We worked there for a while, then as we about to get back on the highway and start hitching, this old guy says 'Where you going?'

"We said 'We're going to California.'

"So, that guy says 'Well, that train there's going to California. Why don't you git on there and it'll take you?' So we did."

Tuck's face is grizzled - he has spent many nights sleeping rough and his voice speaks of tobacco.

He is sitting round a campfire, along with many similarly raggedy hobos in what is known as a hobo jungle.

But these particular men and women are all guests at the National Hobo Convention, held on the second weekend of every August since 1900 in the town of Britt, Iowa.

First devised as a way of putting Britt on the map, it's now the longest running hobo gathering in the US.

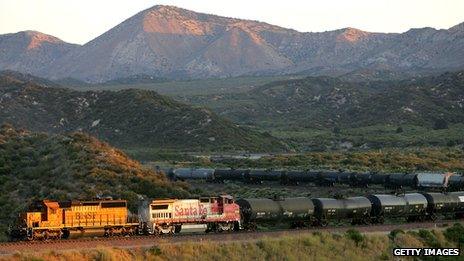

The automobile may rule when it comes to personal transport, but moving freight 500 miles is more efficient by rail.

Private freight lines criss-cross the Rockies, the prairies, and the deserts, sneaking past the back yards of cities and cutting through vast forests.

In the Depression Era of the 1930s, the unemployed took to the rails to try and find work - crossing vast stretches of land in an open grain car, or huddled inside a box car - hiding from the "bulls", as the railroad police were called.

But even before that, post-Civil War soldiers found their way home on the rails. And later, as the push towards the less developed West Coast began, settlers and adventurers alike jumped on board.

Jack London, author of The Call of the Wild and White Fang, famously ended up serving 30 days in jail for vagrancy after train hopping his way to Niagara Falls in the 1890s.

For men like Tuck and his Hobo Jungle companions such as Wrong Way ("guess they call me that 'cos I'm going the wrong way most of the time"), Bolty ("half my face is metal") and Firecracker Wendy ("my dad was an alcoholic, I first jumped the rails going to his funeral"), are what you might term professional hobos - welcomed by the residents of Britt, including museum director, Linda Hughes.

"We have a mulligan stew feed, a ladies tea party, and the election of the 'Hobo King and Queen'."

The atmosphere is friendly - gossip abounds, with tales of playing cat and mouse with the railroad police.

Britt also honours the hobos by providing a section of the local cemetery for their eventual resting place.

But amongst the full-time hobos there is some suspicion about another group of train hoppers - those who have jobs, homes and money - but who choose to do it for adventure and excitement.

"There is an art to getting on and off a moving train. And if you don't know it you can easily be crushed. The train? It won't even notice".

Firecracker Wendy is scornful towards those unprepared.

"You don't always know when you'll be able to get off. You might start off in Sacramento in the desert and by nightfall you'll be in Washington freezing your ass off.

"You know how many kids they pull off frozen to death? Stupid!"

Not that such stories put off the determined recreational riders.

Kevin, now a fire-fighter in Los Angeles, has been train hopping since he was at college, when he discovered the excitement of eluding security, spotting a good container to ride in and hunkering down for a night-time ride through the forests and mountains of his native California, ending up even as far north as Portland, Oregon.

"Back in college we used to build a truck on wheels that fitted on the railway tracks. Sometimes it would take us 11 miles down the rails.

"Then one day we thought we'd try jumping on a train and laying on top of a box car watching the stars, travelling through the mountains and feeling the power of the engine - I was hooked. "

But even the recreational train hoppers have their own code - there are books and websites which tell you about how to find your way around the freight network, how to befriend rail yard staff, and tricks to make riding as safe as possible.

One author boasts of travelling over half a million miles on the rails.

Another warns: "Never jump on a moving train unless you can count the bolts on each wheel - or it's going too fast."

So why do modern Americans, who have safe lives, choose to take up such a dangerous activity?

For Kevin, it represents "the last red-blooded American adventure. There's so much nannyism these days. Government telling you do this and don't do that".

He is retired from train hopping now - lucky not to have been arrested or become one of the fatalities associated with trespassing on railroad property.

There are no statistics available related directly to train hopping.

But in California, there are about 90 railroad-related deaths every year, according to Operation Lifesaver. Two-thirds of the fatalities are people hit by trains while trespassing on the line. Others are killed in their vehicles at rail crossings.

Pete Aadland, executive director of the rail safety charity California Operation Lifeline that promotes safety on the rails, dismisses the notion that train hopping today provides an authentically American experience or any real connection with the spirit of the 1930s.

"There was no work, there was no food, so tens of thousands of men would use the railroads to get to where they could maybe find a job," he says.

"That lure, I think, probably remains today. But I would say that it's not romantic, it's illegal and it's dangerous.

The adrenalin rush associated with riding the rails is often cited by seasoned train hoppers as their drug of choice. With a sense of invincibility, they see it as playing a game with the train. The reality, says Mr Aadland, is far different.

"Losing limbs is very common," he says. "Loads can shift when you're inside of a car. Doors can close and lock - you starve and die of thirst."

But as long as security is patchy and the image of the lonesome hobo, strumming his banjo and reaching for a cigar in the back of a gondola continues, so will train hopping, and all its dangers.

As one train hopper says, "When I'm sitting at my desk, wondering how my life got so dull, I like to think back to an afternoon, sitting on an open box car in Utah with a stack of sheet metal clanking beneath me, basking in the sun, smoking a cigar and gazing at the far horizon."