Newtown: Did the media go too far?

- Published

News trucks crowd the street in the once-sleepy town of Newtown, Connecticut

The mass media coverage of the Newtown shootings produced good information - and a lot of mistakes. Here are four of the issues the coverage has raised.

When the first reports began coming in about a shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School, details were easy to come by, thanks to wall-to-wall media coverage and non-stop social media reports.

But facts were harder to find. Throughout the day news organisations reported developments and then revised them, filling in sketchy, not always accurate details about what happened.

It will be months or even years before its finally understood what happened at Sandy Hook. But in terms of news coverage, some things are becoming clear.

1. Mistakes get amplified

"It's not new that media gets stuff wrong on fast-moving breaking stories," says Edward Wasserman, incoming dean of the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism.

In fact, as Jack Shafer of Reuters points out, external, reporters have got key details wrong early in big stories throughout history.

"What's new is how quickly and how effortlessly this wrong information is published. The scale of error that is quietly becoming tolerable among the media is new," says Wasserman.

One of the biggest mistakes in covering the story was the identification of Ryan Lanza as the gunman, when in fact it was his brother Adam. The mistake was made in good faith, culled by reporters from official sources, since Adam Lanza may have been carrying his brother's identification.

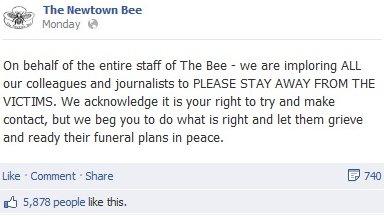

The local paper in Newtown, Connecticut took to Facebook to ask the media for privacy

In the past, this misinformation might have led a nightly news broadcast, but been corrected in time for the first big print stories on the subject.

In this case, it was only a matter of minutes before news sites had found Ryan Lanza's Facebook page and disseminated his photo, external across the air and on the web.

Soon after that people were posting on his Facebook page - and even on his friend's Facebook page, external - accusing them of killing children or endorsing child killers.

In cases likes these, Wasserman says, journalists need to weigh the value of the information, if true, against the damage it would do if false.

"Are you helping to avert harm? Are you enabling people to prepare for an oncoming storm? Is there some countervailing benefit?" he asks.

If the only reason is to beat the competition, he says, it's time to take a breath.

2. Gossip and facts

In the early hours after the shooting there was a limited amount of news trickling out of Connecticut. With web pages and airtime to fill, some non-official reports soon became accepted as fact, partly through the achievement of a sort of media-driven critical mass.

"It's been so convoluted that it's really been difficult to keep track of where some of these narratives originated and the paths they followed from there," says Curtis Brainard, an editor at the Columbia Journalism Review.

After something has been reported enough, it began to seem true, even if it wasn't.

While most news outlets have rigorous standards in place for what qualifies as reportable news and what qualifies as gossip, those lines can get blurred in a breaking news story where details are hard to come by. At some point in the day, nuggets of "news" became conventional wisdom - some without having been confirmed, or debunked, by those reporting them.

Witness, for instance, the repeated assertion that Nancy Lanza, the gunman's mother, was a teacher, external in one of the classrooms at the school.

That information proved to be false - but nevertheless was for a time passed around like fact.

3. The role of children in news

Children were the centre of the Newtown school shooting - 20 children, in fact, fatally wounded in a matter of minutes.

One of the first images to circulate after the shooting showed a line of terrified students being led to safety, external by a state policewoman. In the days following the shooting, the airwaves have been inundated with the faces of the dead children, and of video footage of their peers at funerals.

But many people were repulsed by journalists interviewing children soon after the shooting.

"No amount of information that can justify doing that to the kids," says Mr Wasserman, who says interviews can force children to relive the trauma. "And they're not being interviewed for information, they're being interviewed for colour."

The Newtown Bee captured this image soon after the shooting was reported on a police scanner

In fact, he says, most of the reporting soon after the event was what news organisations call "colour" - the type of detail and background that fills in the scene for the viewer or reader.

After all, the shooting was over. While there were larger questions to be answered - about motive, for example - the on-the-day coverage could really only get "atmospherics".

And so every news crew for miles crammed into tiny Newtown, and the result was that an overwhelmed community was even more overwhelmed - and the news stayed pretty much the same.

4. Correlation and causation

Just because a fact has been confirmed doesn't make it relevant. This is especially true of any developmental issues Adam Lanza may have had (he is anecdotally reported to have had Asperger's or autism).

There is very little reason to mention it in connection with the crime, says Brainard, who heads the Observatory, external, Columbia Journalism Review's science blog.

"It feeds into this idea that if he had autism, that autism played some role in the terrible things he did. If autism played a role in the terrible things he did, then autism can play a role in other people doing terrible things.

"It's a totally twisted chain of logic that results from a fundamental misunderstanding of what autism is," he says, since research shows no link between autism and violence.

But Brainard was encouraged to find that despite some stories trying to draw parallels between any alleged autism and Lanza's crime, they were outnumbered by stories that established facts about the condition: specifically, that it's not associated with violent behaviour.

No matter the challenges, says Wasserman, there is value to having journalists cover stories like these. Even if the event itself lasted only 10 violent minutes, the ensuing days of news coverage can be instructive and useful.

"There's a story that needs to be told," says Mr Wasserman. "We need to know who this guy was and why he turned into this mass killer.

"There are public policy reasons to inquire into such things as school security, gun availability. There are legitimate questions that may require new laws and new oversight."

But to do the story justice, he says, it's important to tell it well.

- Published17 December 2012