Anglo-Indians: Is their culture dying out?

- Published

A product of the British Empire, with a mixture of Western and Indian names, customs and complexions, 2,000 Anglo-Indians are to attend a reunion in Calcutta. But their communities in both the UK and the subcontinent are disappearing, writes Anglo-Indian Kris Griffiths.

Southall in west London is home to Britain's first pub accepting rupees, railway station signs in English and Punjabi, and main thoroughfares alive all year with street food stalls, colourful saris and Bhangra music.

It's my hometown, where I spent my first 20 years among the country's most concentrated population of Indians, but as one of the minority 10% white British inhabitants. Indeed, I was the only white person on my avenue in the years before I left.

My mother is Anglo-Indian, raised in Jamshedpur, near Calcutta, before moving eventually to London's own "Little India". After she married a Welshman, I and my siblings were born fair with blue eyes.

We are symptomatic of the biggest problem facing the global Anglo-Indian community - it is dying out. In the UK and the Commonwealth, it is losing its "Indianness", while back home in India its "Anglo" element is fading.

The definition of Anglo-Indian has become looser in recent decades. It can now denote any mixed British-Indian parentage, but for many its primary meaning refers to people of longstanding mixed lineage, dating back up to 300 years into the subcontinent's colonial past.

In the 18th Century, the British East India Company followed previous Dutch and Portuguese settlers in encouraging employees to marry native women and plant roots. The company would even pay a sum for every child born of these cross-cultural unions.

By the late 19th Century, however, after the Suez Canal's construction had made the long journey shorter, British women were arriving in greater numbers, mixed marriages dwindled and their offspring came to be stigmatised by many Indians as "Kutcha-Butcha" (half-baked bread).

When the British finally departed in 1947 they left behind a Westernised mixed-race subpopulation about 300,000-strong who weren't necessarily glad to see them leave.

"The Anglo-Indians, left in a twilight zone of uncertainty, felt a bitter sense of betrayal," explains Margaret Deefholts, author of two books on Anglo-Indians. "And dismay at the fact that Britain made no effort to offer her swarthier sons any hospitality in the land of their forefathers."

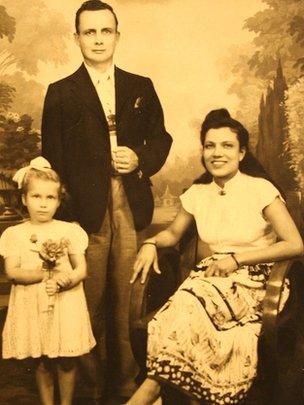

Kris Griffiths' mother left India as a child, with her parents, in the 1950s

They began leaving in droves in the 1950s and 1960s, dispersing throughout Commonwealth countries of Canada, Australia and New Zealand, and their "motherland", the UK.

Joining the exodus were my Anglo-Indian grandmother Esther, six of her siblings, and her daughter Phyllis, my mother. They were bound for London and Toronto.

Most of the Anglo-Indians were more "Anglo" than "Indian". Only darker complexions betrayed their origins.

Otherwise, they dress like the British, their mother tongue is English, with an accentual twang of Indian and they are Christians. They were also stereotyped as drunks in India over the years.

The Anglo-Indians also have a distinctive cuisine - jalfrezi was a staple in our household, but unlike anything on Indian restaurant menus. Then there was pepper water, a spicy thin soup ladled on to rice. Other typical dishes include Country Captain Chicken and Railway Lamb Curry - a throwback to the subcontinent's railways on which many Anglo-Indians worked.

But the younger generations are no longer cooking these dishes. The unique hybrid culture overarching Anglo-Indian identity is expiring, diluted through intermarriage.

"I'm part of that culture now rapidly disappearing as the younger generations merge - as they should - into the mainstream of their adopted countries," says Deefholts, who left India for Canada. "Other than nostalgic reminiscences of an older generation, their Indian past has all but faded into oblivion."

It's uncertain how many Anglo-Indians remain in India, uncounted since a 1941 census. But the estimated 125,000, living mostly in Calcutta and Madras, are enacting the same assimilation - marrying Indians and adopting their culture. They are becoming indistinguishable.

"Previously, the community was too Anglicised - clinging to English traditions and customs," explains Philomena Eaton, convenor of the Calcutta Anglo-Indian Service Society. "But today it's clearly visible that they are much more integrated into society in customs, language, clothing, social interactions, etc. Many Anglos today can easily converse in Hindi and Bengali."

It's a significant turnaround for the community in India, which rarely married Indians before 1947. After that date, they saw employment opportunities diminished by their inability to speak local languages. But today their job prospects are rosier - they are well equipped for multinational customer service positions and speak English fluently.

There are many who want to preserve the Anglo-Indian identity in India. Charles Dias, the parliament's Anglo-Indian representative, has campaigned for greater government support, including reserved university places, new cultural centres and a fresh caste census. An online international marriage portal is being launched in Kerala, enabling youngsters worldwide to marry within the diaspora.

It has been noted in recent years that the number of Anglo-Indians who have succeeded in certain fields is remarkably disproportionate to the community's size. For example, in the music industry there are Engelbert Humperdinck (born Madras), Peter Sarstedt (Delhi) and Cliff Richard (Lucknow).

The looser definition of Anglo-Indian (any mixed British-Indian parentage) encompasses the likes of cricketer Nasser Hussain, footballer Michael Chopra and actor Ben Kingsley.

In 2007, on the BBC's genealogical TV series Who Do You Think You Are? impressionist Alistair McGowan discovered his Anglo-Indian origins. His Calcutta-born father had concealed his Indian nationality until his death, telling McGowan he was darker-skinned after summers spent working in greenhouses.

The same paranoia had apparently afflicted Anglo-Indian Hollywood actress Merle Oberon, who denied her ancestry.

"Throughout my life I had asked him why the family was (in India)," recalled McGowan. "Were his parents Indian? Did he speak Urdu? Did he have an elephant? He always told me simply: 'We were an English family who happened to be living in India'."

In that episode I could relate to McGowan quizzically perusing photos of increasingly Indian-looking ancestors with incongruously English names. My own relatives on the Indian side are named Ronald, Maureen, Nigel, Patricia and Adrian, among others.

I will be meeting hundreds more Anglo-Indians at what might be one of the last triennial Anglo-Indian Reunions in Calcutta in January, when I'll also be visiting my mother's humble hometown for the first time, and she'll be visiting for the last.

Soon all that might remain of Britain's human legacy in India are these ebbing memories and faded photos.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external