The pun conundrum

- Published

To pun or not to pun, that is the question. The lowest form of wordplay, or an ancient art form embraced by the likes of Jesus and Shakespeare, asks Sally Davies.

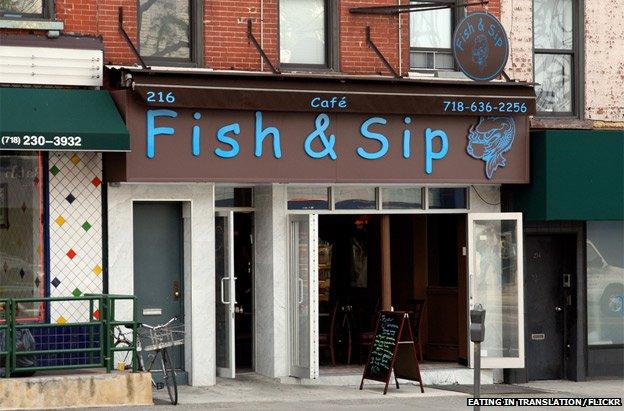

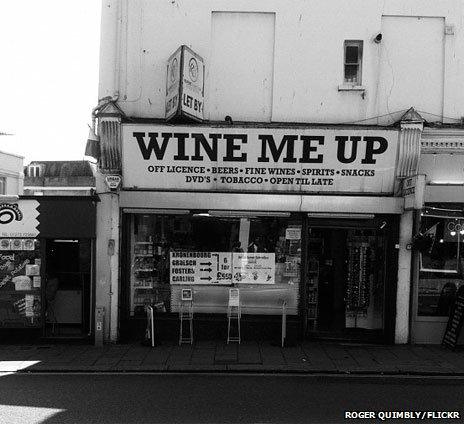

No pun is an island. Within less than a mile of my house in Brooklyn, a wanderer will find:

Fish & Sip, a coffee and seafood joint

Prospect Perk Cafe, an allusion to the restorative properties of caffeine and of nearby Prospect Park

The Winey Neighbor, a liquor store that pays homage to the venerable New York tradition of grumbling about the noise from the apartment next door

Where good humour and refreshments abound, puns seem to follow.

Yet this neat little linguistic device - which exploits the multiple meanings of words or phrases that sound the same or similar - is considered by its detractors to be as irritating as it is irrepressible.

In the English-speaking world, punning is viewed as more of a tic than a trick, a pathological condition whose sufferers are classed as "compulsive", "inveterate" and "unable to help themselves".

The late William Safire, the New York Times's long-time language writer, wrote in 2005 that a pun, external "is to wordplay what dominatrix sex is to foreplay - a stinging whip that elicits groans of guilty pleasure".

Straight puns point to the facile cleverness of headline writers and embarrassing uncles. Elsewhere, they tend to be deployed sparingly, and with a dose of irony.

How did the pun acquire such a dubious reputation?

John Pollack, a former Clinton speechwriter and author of the book The Pun Also Rises, thinks it fell out of favour during the Enlightenment, when the form's reliance on imprecision and silliness was out of kilter with the prevailing spirit of sophistication and rational inquiry.

"Arrant puns" were the subject of attacks by the likes of Joseph Addison, 18th Century London's pre-eminent literary tastemaker. He decried them, external as debased witticisms and exulted that they had been "banished out of the learned world".

Yet Addison's campaign was not enough to expunge the pun from the capital's coffee-houses, where the poet Nicholas Rowe once fell victim to a pun-fuelled prank, described in The Percy Anecdotes, external.

After nagging one of his fellow patrons to borrow a diamond-encrusted snuff box, the owner succumbed, but not before scribbling in its lid the Greek letters phi and rho, or "Fie, Rowe!" An onlooker spoke for many when he remarked that "a man who could make so vile a pun would not scruple to pick a pocket".

But puncraft did not always suffer from such bad PR.

The Roman orators Cicero and Quintilian believed that "paronomasia", the Greek term for punning, was a sign of intellectual suppleness and rhetorical skill.

Jesus himself was a prodigious punster. His declaration that "upon this rock I will build my church" famously played on the way Peter's name echoed the Ancient Greek word for rock, "petra". Jesus may have also salted his speech with puns on Aramaic words, external, the language of everyday communication. When he condemns the Pharisees for letting punctilious piety blind them to mercy, Jesus calls them "blind guides, which strain at a gnat [galma], and swallow a camel [gamla]".

Here, then, puns seem to serve a purpose beyond the merely frivolous - to impart shades of meaning in an economical fashion, perhaps, or to render lessons and concepts more vivid and memorable to listeners.

In other cases, darker psychological forces may underpin the pun. The humour theorist Charles Gruner has argued that puns are a product of humans' adaptive tendency towards competitiveness. We may groan at puns as an acknowledgement that we have been outplayed by a speaker who has asserted his or her superiority over us.

Sigmund Freud, by contrast, identified puns as an admission of weakness, a psychic release-valve in which humour alleviates the stress of repressing unpleasant truths.

In one of his essays, external, Freud tells the story of a poet who sat next to Baron Rothschild at a dinner. The banker "treated me quite famillionairely", claimed the poet - an amusing phrase that softened the blow of being condescended to, according to Freud.

The psychiatrist, who was also interested in how Jewish humour developed its distinctive wryness under conditions of persecution, said that such jokes were "a victorious assertion of the ego's invulnerability".

A Freudian reading of the humble pun, then, might suggest it is a response to despair, a subversive device whose tidiness enhances the illusion of self-mastery.

Inferiority was at stake in Shakespeare's puns, too.

The characters in his plays that begin the bawdy jests and elaborate badinage are almost always pages and buffoons, commoners at the mercy of their aristocratic overlords.

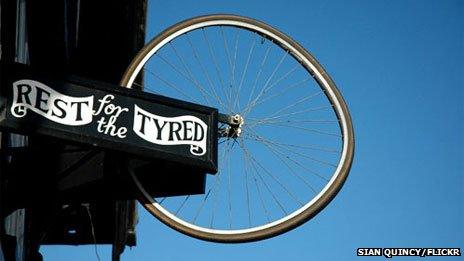

Hairdressers are masters of the art

Puns give them a cloak of deniability - the joke permits ordinary folk to make light of their social betters without violating the norms of respect. Sex and death were these characters' favoured subjects - Shakespeare seemed to intuit what Freud would argue some 300 years later, that humour helps us cope with the terrifying and taboo.

So in this scene from Hamlet, the tortured prince banters with a gravedigger in the midst of his macabre work, playing on the semantics of the word "lie":

Hamlet: Whose grave is this, sirrah?

Gravedigger: Mine, sir.

Hamlet: I think it be thine, indeed; for thou liest in't.

Gravedigger: You lie out on't, sir, and therefore it is not yours: for my part, I do not lie in't, and yet it is mine.

Hamlet: Thou dost lie in't, to be in't and say it is thine: 'tis for the dead, not for the quick; therefore thou liest.

The purposes of puns seem to be as diverse as the circumstances in which they appear.

But regardless of its rationale, punning is clearly more than a mere linguistic fillip. And there may be reason to hope that the internet will restore its reputation. The efflorescence of punnery on social networking sites like Twitter, Tumblr and Reddit, which bulge with the fruits of meme generators, suggests that puns have become acceptable as part of the online conversation.

It may be only a matter of time until the pun rises once again. But for now, its future is an impunderable question.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external