Why are vandalism rates falling?

- Published

Vandalism in the UK is falling at a quicker rate than almost any other type of crime, according to official figures. What are the possible reasons behind this?

An Ipswich teenager is fined £800 for damaging cars in a "drunken kung fu kicking spree", external. A Dundee pigeon fancier is left heartbroken after his loft is burned down., external Police launch an inquiry after stained glass windows are smashed in a Great Yarmouth church, external.

Three incidents out of hundreds in the past week, suggesting that mindless destruction of property by "yobs" is still a depressingly predictable feature of life in the UK.

The idea that vandalism might be on the wane - that the authorities have somehow got it under control - will sound like a sick joke to those that have to live with it every day.

In the 2011 riots, the country witnessed an orgy of destruction and arson on a scale not seen before - proof surely that the current generation is the most mindlessly destructive ever.

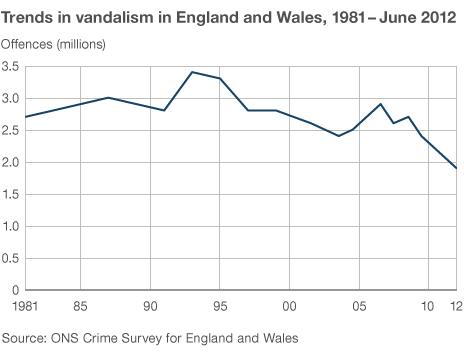

Yet the official figures tell a very different story. There has been a reduction in vandalism incidents per 1,000 households of 37% since March 2007, according to the Crime Survey of England and Wales. It is a similar story in Scotland, where vandalism - arson, graffiti, broken windows and so on - is down 21% since 2008/09, according to the Scottish Crime Survey, external.

That is a remarkable fall by any standards - and the trend is expected to be confirmed on Thursday when the Office for National Statistics releases its latest crime statistics.

Criminologists are already at a loss to explain why overall crime levels, which are meant to increase during tough economic times, are currently falling. Even less research has been done on why vandalism is falling faster than most other types of crime. But there are a few theories.

People have stopped reporting vandalism

This is the most simple explanation - the statistics are simply wrong. People are so used to vandalism that they no longer bother reporting it to the authorities.

The flaw with this argument is that the big reduction in vandalism has been picked up by crime surveys, which are based on interviews with random members of the public, rather than raw crime statistics, and that the big reduction has suddenly happened over the past four or five years.

Criminologist Mike Hough, who helped devise the British Crime Survey, as it was then called, admits it is not perfect. No survey ever is.

But the fact that recorded incidents of criminal damage - police jargon for vandalism - have also fallen sharply, from 1,185,040 in 2006/07 to 598,958 in 2011/12, suggests it is more than a statistical blip.

"I don't think there is any reason for thinking the findings are dodgy in any way," says Hough, co-director of the Institute for Criminal Policy Research. "It is probably real."

Stuff is harder to vandalise

Can this bus shelter beat the vandals?

Traditional targets for vandalism have become more difficult to destroy or deface, according to Clear Channel, which supplies bus shelters and other street furniture to 350 local authorities. Their products double as advertising hoardings.

"Many of our shelters are fitted with fortressing materials which does significantly deter vandals. We've noticed great success in Swindon, Cardiff and Bristol, where vandalism on shelters fitted with fortressing materials is down to negligible levels," says UK operations director Mark Webb.

"Crucially, we also apply the 'broken window' effect. Our maintenance teams responding quickly when graffiti and vandalism does occur demonstrates that we take pride in the area and definitely helps to reduce vandalism in the future."

Anti-social behaviour crackdowns are working

Labour's attempt to tackle the sort of low-level nuisance normally left to local councillors was ridiculed at the time and its main weapon - Anti-social behaviour orders, or Asbos - met with mixed results. They are about to be replaced by a new kind of order, which the coalition government claims will be more carefully targeted.

But some local authorities have claimed remarkable success in using Asbos to improve the quality of life for residents on some of the country's toughest estates.

For example, Camden, in north London, has seen year-on-year reductions in vandalism, due in part to the use of Asbos to target known troublemakers.

"This reduces anti-social behaviour by removing the worst offenders but is also shown to have a knock-on-effect on other offenders - by deterring them from areas, for example," says a council spokesman.

The downside of such an approach, critics say, is that the problem is simply shifted to other areas with less zealous enforcement.

Note: Data refers to different time periods: a) 1981-99 refers to a calendar year, b) 2001/2-2009/10 refers to a financial year, c) Last two data points refer to the year from July to June

Vandalism prevention is more sophisticated

Local authorities and police have got smarter at tackling vandalism in recent years - although there is concern that future efforts will be severely hampered by budget cuts.

Some councils use statistical analysis techniques pioneered in US cities like New York and Chicago to target resources where they are most needed.

They also aim to deal with minor vandalism rapidly to stop neighbourhoods falling into disrepair and becoming breeding grounds for more serious crime - the so-called "broken windows" strategy.

Cotgrave, in Nottinghamshire, a deprived former mining village, has seen a 48% reduction in vandalism, thanks to that much-vaunted but rarely achieved public service ideal "multi-agency working", says the Local Government Association.

"The [Tory-controlled] council worked with the police, the fire service and Nottinghamshire County Cricket Club to provide diversionary activity for young people, used gating orders to close alleyways being used at 'rat runs', demolished a row of unused garages attracting vandalism," says a spokesman.

"The council identified a number of problem families causing a lot of the anti-social behaviour and used a multi-agency case panel approach to deal with their issues, including support and enforcement where necessary."

There was also a crackdown on under-age alcohol sales.

"This kind of work is a typical of the work councils co-ordinate in troubled communities," says an LGA spokesman.

"Over the past year or so we have not seen as much graffiti as there used to be in the past so it is probably working," says Hayley Anne Chewings, Labour councillor for Cotgrave, who credits local youth centre Cotgrave Positive Futures for the turnaround.

Smartphones have killed boredom

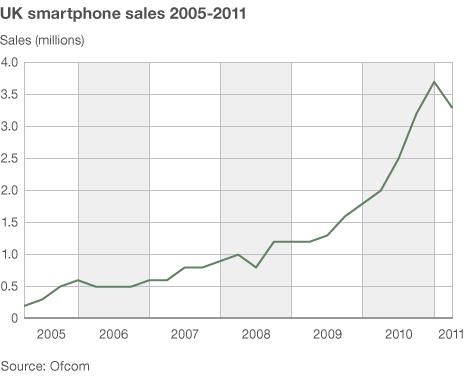

Vandalism began to fall sharply in 2006/07 - about the same time as smartphone sales began to take off in the UK.

Research last year by Ofcom found 7% of teenagers spent less time socialising with friends since they got a smartphone.

Would it be too much of a stretch to suggest they also spend less time hanging around on street corners and vandalising things?

"There are so many things for kids now," says Kito, a 30-year-old Camden youth worker.

"Why waste their time vandalising when they could be on their BB [Blackberry] talking to girls or on YouTube putting up their music videos? They have got a lot of things to keep them occupied. They don't need to be bored now."

The average 11- to 14-year-old spends 13 hours a week playing computer games, increasingly on their smartphones, GameTrak figures show. If true, this would not leave a great deal of time for much else.

Note: Figures for England, Scotland and Wales. Only represents consumer sales, most business connections are excluded

Social media is the new graffiti

Graffiti was traditionally the only means love or hate-filled teenagers had of letting the world know about their passions. Now, thanks to Twitter and Facebook, they can literally let the world know about it - and no-one will come along and remove it.

"Vandalising and spraying - the local council will just come and take it off," says Kito, a youth worker of the Queen's Crescent Youth Club.

"They will wash it off. So you put it up, they wash it off, you put it up. But if you put it up on your BB it's yours, it's your personal message and nobody bothers you."

Vandalism is increasingly seen as a pointless activity. As one teenage girl at the Queen's Crescent Youth Club put it: "If I get angry about something, I go on Facebook."

Young people are drinking less

Criminologist Mike Hough believes this could be the one of the key factors behind the reduction in vandalism. Drink is a major factor in a lot of criminal damage, he argues, and the steady reduction in alcohol consumption among young people - despite the lurid headlines about binge drinking - is too statistically significant to ignore.

As for why teenagers might be drinking less, he says health messages may be getting through, or they might have "seen their older brothers and sisters getting smashed" and decided it was uncool.

Lead has been removed from petrol

This might sound like the craziest explanation of all. But there is a growing body of research which suggests the sharp drop in violent crime in many Western cities might be down to a fall in the amount of lead in the atmosphere since it was banned from paint and petrol.

Exposure to lead in childhood has been shown to lower IQ and lead to more impulsive and violent behaviour. Dr David Green, of the Civitas think tank, has suggested it could be a factor in the dramatic surge in crime in the late 1980s, which peaked in 1993, and has been falling ever since.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external