Have train fares gone up or down since British Rail?

- Published

- comments

It is 20 years since rail privatisation was set in motion. Are fares higher or lower today than they were under British Rail?

January is the traditional time of year for teeth gnashing from rail passengers as fares rise again.

Twenty years ago, the wheels of rail privatisation were set in motion. In January 1993, John Major's government enacted the British Coal and British Rail (Transfer Proposals) Act 1993, external.

At the time, the message was that fares would rise no faster under the new privatised railway than under BR. It was suggested that they might even fall.

"I see no reason why fares should increase faster under the new system than they do under the present nationalised industry structure," Transport Secretary John MacGregor told the House of Commons in February 1993. "In many cases, they will be more flexible and will be reduced."

So two decades on, what has happened?

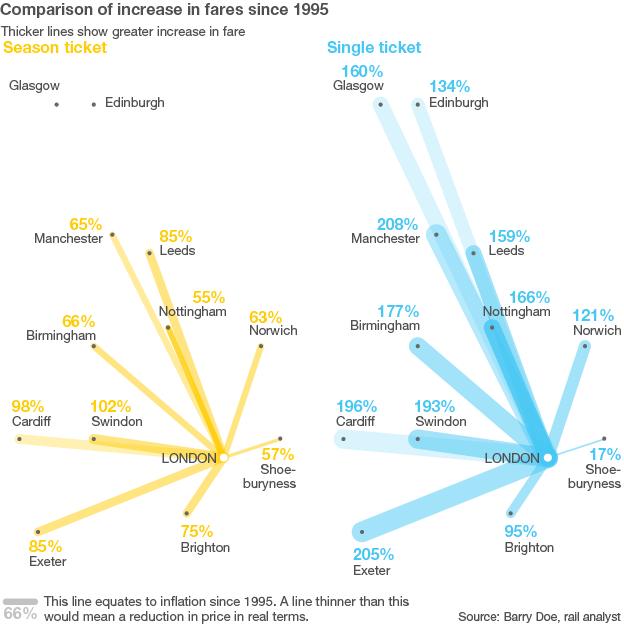

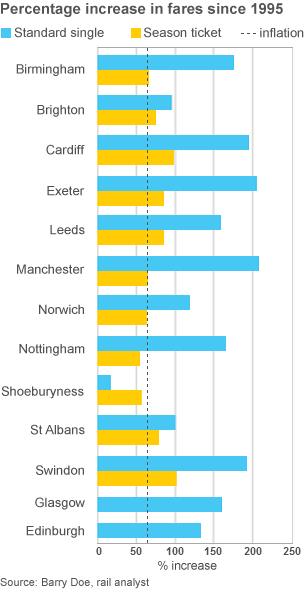

Since the last set of British Rail fares were published in June 1995, inflation measured by the Retail Prices Index (RPI) has been 66%, according to research by fares expert Barry Doe for Rail Magazine, external.

Doe's figures show a huge variation in fares since privatisation.

A single from London to Manchester has gone up by 208%, up from £50 in 1995 to £154 today. That is more than three times the rate of inflation.

But a season ticket for the same journey has risen by only 65% - just less than inflation.

Doe's research considers walk-on fares, which include season tickets, but not tickets that are bought in advance. Advance tickets are cheaper but there is no solid data on the cost or number sold.

Peak-time single tickets have risen sharply. For example, a single from London to Glasgow, which was £65 in 1995, is now £169 - a rise of 160%. A single to Exeter was £37.50 but is now £114.50 - a rise of 205%. London to Swindon has gone from £20 to £58.50, a rise of 193%.

Yet at the same time, season ticket price rises hover just below or slightly above the rate of inflation, with an increase of between 55% and 80%. A season ticket from Nottingham or Norwich to London has risen by 55% and 63% respectively.

Like season tickets, the price of off-peak returns has been capped by government since privatisation. A return - coming back within a month from London to Birmingham costs £49 today compared with £31 in 1995 - a rise of only 58%, well below the rate of inflation. This is with Virgin, the same company that operates expensive singles to Glasgow and Manchester.

There are anomalies. Train operator C2C, for example, operates the line from London to Shoeburyness, in Essex. The cost of the journey is far cheaper in real terms across all ticket types than it used to be. A single has risen by just 17%, while a season ticket has gone up by 57%.

At privatisation, it was felt that certain customers needed protection, says Mark Smith, founder of website The Man in Seat Sixty-One, external, who used to set fares at the Department for Transport.

The theory was that at certain times of day, such as during rush hour, the market would not operate a level playing field.

Ever since, the government has protected season tickets and off-peak returns. Before 2004, rail operators could only raise regulated fares by inflation -1%. From that year, this became inflation +1%.

Meanwhile, other fares were unregulated, meaning the train companies were allowed to set them as they wished.

The feeling was that those travelling long distance in peak time would be mainly business travellers who could afford it. But the system has led to massive variation, says Doe.

"Because operators were forced to introduce capping, they were forced to put unregulated fares up a lot." Commuters have been "featherbedded" but other passengers have been hit hard, Doe argues.

There is a double reason why unregulated fares rise faster than regulated fares, says Christian Wolmar, author of Broken Rails.

First because they can, he says - there is no government control. But second, the rail companies keep all the money they make on price increases on unregulated journeys. On regulated fares, the government receives the above inflation increase.

"The system has an incentive to put unregulated fares up by more than the amount of regulated fares because the train companies retain all the money," Wolmar says.

But the Association of Train Operating Companies (ATOC) says that Doe's figures miss out the million advanced tickets it sells a week.

"Mr Doe's table quotes London to Edinburgh as costing £152 for a single," an ATOC spokesman says. "But one check of the East Coast website and you'll find that you can make that journey for less than £29. That's significantly cheaper than in 1995."

It points out that only between 2% and 4% of tickets sold are the flexible Anytime tickets, such as the single ticket measured by Doe.

ATOC admits it doesn't have figures on the proportion of tickets sold that are "advance". According to Lennon rail ticket sales database, about 4% of tickets sold between November 2010 and November 2011 were "advance".

So while few people travel on the most expensive single or on advance tickets, most rail users use season tickets or off-peak returns.

There are no figures showing the average cost per passenger mile.

ATOC says that in 1994-95 the average cost of a single journey was £4.82 compared with £4.95 in 2011-12. This is a rise of 2.7% when adjusted for inflation, the spokesman says. But combining all journeys both long and short, it doesn't give a breakdown of which journeys are rising in cost and which are falling.

The organisation adds that four out of five journeys today are made on a rail card or advanced ticket.

Advance tickets are all very well, but don't suit everyone, says Christian Wolmar, author of Broken Rails.

"They (the train companies) have people over a barrel," Wolmar says. "If you have to travel at 8.30 in the morning you have to. You don't have the choice of waiting for the 9.30."

But Smith believes privatisation has delivered a more intelligent fare structure.

People might assume that fares would have gone up slower under British Rail, says Smith. But for commuters, the reverse might have been true as there was no capping of fares under BR, he points out.

On longer distance routes, he says, price variation has allowed the rail companies to compete with both coach companies on the bargain advance tickets and airlines for the expensive peak time seats.

"In practice it's been a success. It's been one of the factors at getting more people travelling longer distance by rail while at the same time raising more revenue. So in some ways privatisation has been a good thing."

There is more to a railway's success than just low fares. Other measures are safety, punctuality, comfort, frequency of service, convenience and simplicity. On many of these, the privatised railways have a good record.

On simplicity, the network seems to get a big fail from commentators. Triangular journeys (returning via a different route) are harder now than under British Rail, says Smith.

And some fare rises are exceptionally complicated, according to Doe's research. In a few cases, off-peak returns have risen hugely even though these fares, in theory, are regulated. A London to Leeds return is now £154, up from £55 in 1995.

Doe says these big rises occur when a train operator gets around the government cap by removing the super saver and replacing it with a more expensive super off-peak ticket, before then bringing in a more expensive saver, known as off-peak return.

Confused? Most people are, says Matthew Engel, author of Eleven Minutes Late. Visitors to Britain are regularly forced to pay more than they should simply because they don't understand the multiplicity of ticket types and conditions, he says. "I'm convinced the train operating companies have not allowed any rationalisation because they make money from this. They know that there's only Barry Doe who understands (the correct fare)."

Critics argue that privatisation has led to big fare rises despite increased public subsidy. Money has had to be found for salaries and dividends, they claim. And no-one knows why rail infrastructure costs so much more in Britain than the rest of Europe.

According to ATOC, train companies make only "modest" profits, averaging 3% of revenue.

Total government subsidy for the railways increased from £2.17bn in 1992-93 to £2.59bn in 2002-03, according to figures from the Office of Rail Regulation. It peaked in 2006/07 at £6.3bn, before falling back to £3.9bn in 2011-12.

Rail Minister Simon Burns says privatisation was "the right decision 20 years ago and is the right decision for today's railways."

Under British Rail there was a lack of investment that today's privatised railway has had to make up for, he argues.

"There were far fewer trains, more of them ran late, when they arrived at all, and since privatisation passenger satisfaction has improved significantly."

Re-nationalisation is not a possibility in a cash-strapped country. But Doe's research raises the question of fairness. Are commuters being overprotected?

Most of them don't work out how many miles a year they do, he says. "Brighton to London is 500 miles a week." But there's no appetite to tinker with the status quo, Doe says. Commuters are a "big lobby group" who neither the Conservatives or Labour want to antagonise.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external