A Point of View: Staring at the Shard

- Published

Will Self confesses to being dazzled by the skyscrapers that dominate urban skylines, but wonders if they have overshadowed visionary dreams of making cities better places to live.

It was said of the French writer Guy de Maupassant that he ate dinner in the restaurant of the Eiffel Tower every night of the week, and when asked why, replied, "Because it's the only place in Paris from where you can't see the Eiffel Tower."

While this anecdote has the distinct whiff of too-good-to-be-true about it, I can assure you that my own peak perspective is 100% genuine.

So taken am I by the spectacle of Renzo Piano's Shard lightsabering up into the London night, that I've taken to sleeping in the spare room, from where I have a good view of this, currently the loftiest building in Western Europe. I even leave the blind up, so that when I wake in the small hours I can contemplate the Shard under different light and weather conditions.

This is not, I hasten to assure you, because I think the building has any architectural merit whatsoever. Rather, with its catchy nickname, and gross simplification of form, it's just the latest exemplar of what the architectural critic Owen Hatherley has characterised as the boosterist cliche, external of creating structures that are simultaneously a logo and an icon.

There's this, and there's also the ephemerality of the Shard. I have a friend who lives in a house in its shadow that was built in the 1600s, and given the 75-year specification of this scintillating spire and our proven capacity for doing away with large and recently-built buildings, I've no doubt that his humble abode will still be there long after it has gone.

Indeed, at New Year's Eve, standing on top of Brockwell Park in Brixton, and looking at the starbursts and glittery flak explode over the Thames while the London Eye was transformed into a gigantic Catherine wheel, it occurred to me that the contemporary metropolitan skyline is really only a fireworks display of decades-long duration. A burst of aerial illumination intended to provoke awe, but doomed, eventually, to subside into darkness.

As it is to London, so it is to other British cities. Over the past 20 years a series of signature buildings has lanced up into heavens, forms that by day have the aspect of grossly enlarged desktop toys, but which by night resemble nothing so much as the over-lit rockets and gantries of some Cape Kennedy of the collective British psyche.

It's as if our architects, civil engineers and urban planners were summoning us not to the dull confinement of the workaday, but to an exciting mass exodus, one in which we will all become colonists of the future. I say "as if" because, of course, these gleaming nacelles are no more the product of careful arrangement, or thoughtful dispensation, than the up-thrust finials and melting buttresses of a termite heap.

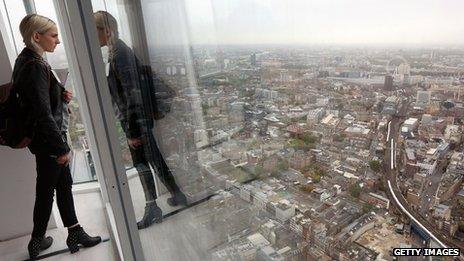

Inside the Shard - one of the few places in London you can't see the building

Not, I'm sure, that those who believe they're responsible for the character of our built environment would view it this way.

After all, never before in our history have quite so many people spent quite so much time drawing up plans, conducting surveys and initiating impact studies. Never before has every single square foot of available building land been pored over with quite so much attention, nor has each aesthetic detail and design feature of our habitation been subjected to as systematic a supervision.

Moreover, our journeys through this maze of quantification are subjected to the most accurate possible computer modelling, with a view to achieving that quintessentially modern desideratum: smooth traffic flow. And yet, despite all of this the end result is still an anarchic hugger-mugger of concrete, brick, steel and glass, typified by cul-de-sacs full of double-parked cars, and arterial roads clotted with traffic jams.

How can it be that we've arrived at this strange impasse, where, instead of being citizens of a noble acropolis presided over by a genius loci, we seem the short-let tenants of a sandpit played in by a giant (and not especially imaginative) toddler?

It's true that historically Britain faces an uphill struggle when it comes to effective and rational planning. As the first society to be industrialised and urbanised, our relatively small island was already thickly layered with sectional and individual interests before any effective civic authority existed. Hence, in longstanding built-up areas planning has always been a piecemeal and rearguard action against the successful redbrick invader.

There's also the paradoxical role played by the two great 20th Century theorists of urban planning: Ebenezer Howard, the founder of the native garden city movement, and Le Corbusier, the continental promoter of the city as a "machine for living".

The two are often portrayed as polar opposites: Howard the believer in privet hedges, and low-rise bungaloid development ranged along parabolic crescents; Le Corbusier, the apostle of the perpendicular skyscraper right-angling up from a grid-pattern of flyovers.

But in fact both were responding to what they perceived as the human cost exacted by the chaotic growth of European cities. Both saw the vital need for people of all classes to have well-lit, unpolluted and safe places to live, characterised by large amounts of green space, and both sought to reconcile socialistic aspirations and capitalistic prerogatives within beautiful and sustainable urban environments.

That Howard tended to a more laissez-faire model of how this was to be achieved - the garden city acting as a magnetic attractor by its obvious virtues alone - while Le Corbusier saw the need for a firmly dirigiste, top-down approach, can be explained in part by national temperament, in part by cultural experience.

Howard was a true son of the Arts & Crafts movement, and as such, although he looked forward practically to clean and ubiquitous electrical power, he looked backward, idealistically, to the vernacular architecture of a supposed merry and harmonious England. This is why, to this day, you can stand on a suburban pavement in Uxbridge or Uttoxeter, and see a shiny new car parked beside a lichen-covered lych-gate.

However, you can also look up from the half-timbered facades of "Tudorbethan" semis to see powering along the horizon a file of Le Corbusier-style multi-storey blocks. They may not be standing in the acres of open parkland as he would have wanted, but here at least the victory of the machines that he prophesied seems secure.

This dual and poorly-enacted heritage perhaps best explains the curiously confused aspect of our cities. Indeed, you can walk through them pointing to first one feature then the next, and identify them as the bastard children of either one or the other of these visionaries.

Howard's plans were ruined by the private car - the rise of which he didn't fully anticipate. Le Corbusier's were wrecked by the adoption of high rises for human habitation - something he never envisaged, believing that most people should live in comparatively low-rise apartment buildings. And underlying this confusion is a further derogation - that of an ideal both men shared, which was that the municipalities of the future should utilise increasing land-values to improve the collective lot.

Lying abed, looking at the Emerald City of unfettered finance capital coruscating across the rooftops of the Victorian corridor streets that Le Corbusier and Howard so decried, I can appreciate that enacted here is the most important axiom of contemporary architecture - form follows finance.

With its short life and great height, the spiky Shard graphically illustrates exponentially increasing inner-city land values, while the chaos of old and new masonry surrounding it testifies to the greed and short-termism of successive generations.

There's just one massive mitigating factor in this prospect - despite the Wizard of Oz-hollowness of the illusion, the spectacle remains entirely bewitching. Indeed, I doubt anyone would ever change their sleeping arrangements in order to survey a well-planned city. It's this essential ambivalence we all feel about the urban landscape - that its sordidness and its beauty are somehow inseparable - that unites me with De Maupassant across both the Channel and the years.

And high buildings, in particular, arouse in us these painfully comingled feelings of love and hatred. We love them for the new prospects they afford us of our cities, while loathing them for the way they belittle us.

De Maupassant may have dined upright in the Eiffel Tower gazing down over Paris, while I'm supine in London staring up at the Shard. However, au fond, I think we share the same point of view.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external