Britain's £1m and £100m banknotes

- Published

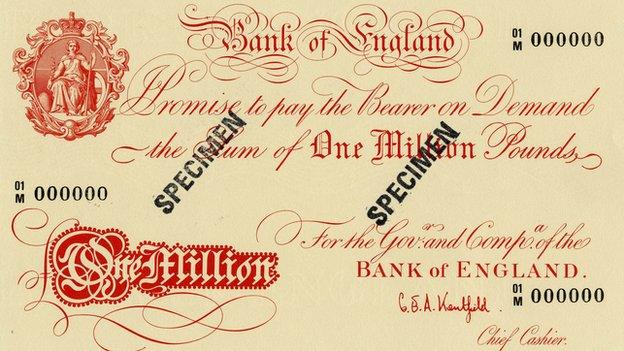

Carefully guarded in the Bank of England's vaults are a small number of very large banknotes. Called "giants" and "titans", they are not in circulation for good reason - each is worth a sum of money most of us can only dream of. What are they for?

"When it comes to a £1m note, everybody thinks, 'What a fantastic thing'," says Barnaby Faull, head of the banknote department at the auctioneers Spink.

"What most people don't realise is they do actually exist."

But the £1m pound note - known as a "giant" - is not in circulation and it is inconceivable it will be made available from cashpoints. How many of us would risk carrying one around in our wallet, let alone have sufficient funds in our account to get one out?

But even the monetary value of the giant is relatively small compared to the "titan" - a banknote that promises to pay its bearer £100m.

Impractical though they are for everyday use, both play a vital role in the British currency system, by backing the value of the everyday notes issued by commercial banks in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Many people know how a Scottish fiver can be viewed with suspicion by businesses in England. This backing aims to maintain everyone's confidence in the value the notes represent.

For every pound an authorised Scottish or Northern Irish bank wants to print in the form of its own notes, it has to deposit the equivalent amount in sterling with the Bank of England.

If necessary, notes from, for example, a struggling Scottish bank could be replaced with regular Bank of England cash.

"If there was an unfortunate situation when one of the banks failed, note holders would have the confidence that their notes were still valued as it said on them," says Victoria Cleland, head of notes at the Bank of England.

Auctioneer Barnaby Faull on the secrecy around the big banknotes

So Scottish and Northern Irish banks supply their backing, which pays for the creation of giants and titans. The Bank of England prints them internally, rather than with its normal commercial printers. They are then locked away very carefully.

Cleland says it's much more efficient than having thousands of cages of Bank of England notes stored around the country. In a turbulent financial era, this backing matters more than ever.

Very occasionally, older £1m notes have escaped from the Bank of England's vaults and archives.

Faull recalls being offered a cancelled £1m note issued in connection with the Marshall Plan - the US's post-war aid programme to Britain. It had been presented to a retiring chief cashier and his widow later offered it for sale.

He says the Bank of England asked him not to publicise the sale. "Million pound notes were not supposed to be out in the open."

Scottish notes are guaranteed by giants and titans

But the system which today's giants and titans help guarantee could face new scrutiny if Scotland votes for independence next year. The Scottish National Party is proposing that an independent Scotland arranges with the rest of the UK and the Bank of England to continue to be part of the sterling family.

But some ask whether political independence could lead to doubt as to how far London would back Scotland financially. And during a financial crisis, doubt is dangerous.

Ironically, although distinctive Scottish banknotes are a symbol of separate identity, it might be better for an independent Scotland to use Bank of England money.

Angus Armstrong, of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research and a former senior Treasury official, suggests this could help remove any doubt.

"It is one of the paradoxes of independence for countries today that some of the freedoms that you currently enjoy may become unavailable to you," he says.

Were this to happen, giants and titans may no longer be needed to back separate Scottish notes. But could they ever find new, more public roles?

The author Mark Twain wrote a short story, The Million Pound Bank Note, external (later made into a film starring Gregory Peck), in which a penniless sailor is given the note, little knowing he is the subject of a bet between two brothers.

One brother believes the note will be useless. The other believes that, even though no business will be able to offer change, the sailor's mere possession of the note will mean that everyone will offer him credit, believing him to be rich.

High-value notes could also emerge were Britain ever to suffer hyperinflation. By way of warning, the Bank of England Museum currently displays a 20bn mark note issued in Germany in the early 1920s.

But for now giants and titans are the discreet but utterly reliable guarantors of the status quo.

When the Queen visited the Bank of England in December, she signed a decorative £1m note, not formally issued by the Bank, now also on display in the museum.

The rest of us must be content with fivers, tenners, twenties and fifties - and the Scottish hundreds.

Listen to the full report on Analysis on BBC Radio 4 on Monday 28 January, 20:30 GMT and Sunday, at 21:30 GMT.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external