HS2: 20 reasons why it can take 20 years to build a railway

- Published

The HS rail link won't be finished until 2033 so why does it take two decades to finish a project like this?

The government has announced a provisional route for the second stage of the High Speed 2 rail link between London and the north of England.

Its second phase - a Y-shaped section from Birmingham to Leeds and Manchester - won't be finished for 20 years. Those working on the project say its sheer scale and complexity explains the length of time.

But there are already critics of the timetable who believe it could be completed sooner. The 20-year time lag is a "complete nonsense" says Sir Peter Hall, professor of planning and regeneration at The Bartlett, University College London. If it wasn't for political considerations, the line could be built in about 10 years, he says.

But what are some of the reasons that could explain a 20-year project?

1. A history of delays

Any major infrastructure project in the UK has the potential to take a long time. The building of HS1 - the Channel Tunnel Rail Link - was completed 16 years after Michael Heseltine first announced it to the Conservative Party Conference in 1991. That was only 68 miles. HS2 will be 330 miles. It's not just railway lines. The public inquiry alone for Heathrow Terminal 5 took nearly four years.

2. Splitting it into two phases

The biggest source of delay is that the HS2 project has been split into two.

Construction for the London to Birmingham route will begin in 2017 and be finished by 2026. The Birmingham to Manchester/Leeds construction starts in the mid 2020s and is due to be finished by 2032 or 2033.

Prof Hall, an advocate of high speed rail, says the phasing makes little sense. Why not start on both now so that they will be finished sooner? The same thing happened with the Channel Tunnel rail link, which could have been finished in 2003 but was done in two phases, he says. "The whole (HS2) line could be open in theory by 2023," he argues.

3. Spreading the finance

An artist's impression of the planned Birmingham and Fazeley viaduct

The splitting into two phases is because the planning and design work is so time consuming, a spokesman for HS2 maintains. But it's easy to see a financial case for doing it.

HS2 costs £32bn. With the £15bn Crossrail not due to finish until 2018, the government is keen to spread the cost of the new North-South railway over a longer period.

Once Crossrail is finished, the £2bn a year that is being put into it will shift to HS2, says David Meechan, a spokesman for HS2. In other words, a longer timescale allows more of the financial burden to be passed on to the next generation.

4. Consultation

Consulting the public takes time. The route for phase one of the line - London to Birmingham - was initially published in December 2010. Consultation then took place and in January 2012 changes were announced. There was more protection for sensitive areas in the Chilterns and Buckinghamshire, external. But that's not the end of the process.

An Hitachi Javelin train on the HS1 line

5. More consultation

Even after phase one's route was tweaked there began a second stage of consultation and planning. Detailed engineering work has to be done looking at the exact route of the line. There are environmental impact assessments. Community forums are being organised along the route. Minor tweaks are still possible. It means that phase one will not be ready to be put before parliament until the end of 2013. That's still not the end of the process.

The same process then has to start all over again for phase two - the Y-shaped route north of Birmingham that has just been announced. It begins with compensation for property owners facing "exceptional hardship", external. Then the full consultation programme begins.

6. Buying land and people's houses

The government doesn't yet own the land. And to build a railway you need far more land than the line itself will occupy, says Ben Ruse, a spokesman for HS1, also known as the Channel Tunnel Rail Link. "You need vast swathes of land, for instance somewhere to store the machinery and materials." It's complicated and expensive.

The typical purchase price is roughly the market rate plus 10%, suggests Ruse. It can be a big business blocking the route or "Bob in his allotment". Everyone needs to be talked to and negotiated with.

"We are not at the stage of CPOs on phase 1 yet," says Meechan. "But we have said that 338 dwellings along the 140 mile route between London and the West Midlands will have to be demolished to make way for the new line. Most of these will be close to the redeveloped station at Euston."

7. Demolishing Camden

The most disrupted area in the country will be to the north of London's Euston station. More than half of the properties affected by the scheme between London and Birmingham are in and around Camden.

Euston is being redeveloped. As part of that a section of Camden will need to be demolished.

Andrew McNaughton, HS2 technical director, told the Engineer magazine, external last May that the London section would be the most time-consuming.

"The critical part of the construction is at the south end, with the complete rebuilding and expansion of Euston station and the long tunnels through London; that's a seven to eight-year job," McNaughton said. "Out in the greenfield away from London, most of the route can be built in two years."

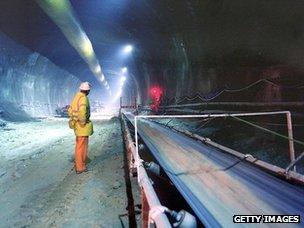

8. Tunnels

The sheer volume of tunnelling is a major headache. The route has been revised, with tunnels extended and several more added, in an attempt to remove noise and visual impacts.

Around 22.5 miles (36km) of the phase one route will now be completely enclosed in tunnel. That is 18% of the 140 miles of rail from London to Birmingham.

North Downs tunnel

Much of that is "green tunnels". This is essentially a deep cutting with a tube put into it, over which grass, trees and soil are placed. It is not as deep as a normal tunnel, and is much cheaper to construct.

The rest is "bored" tunnelling, an extremely time-consuming process.

"Tunnelling presents a real engineering challenge," says Ben Ruse, HS1 spokesman.

"The North Downs Tunnel in Kent for HS1 was a mile or so long. A tunnel borer started from each end. When they met in the middle it was 4mm apart. And the engineers were shaking their heads."

Four millimetres was fine and safe, he says, but the engineers wanted to be closer. It shows how exact the process has become.

9. Archaeology

When any big road or rail line is cut through the British countryside there needs to be archaeological investigation to make sure vital sites will not be destroyed.

The HS2 line probably won't be comparable with the painstaking efforts made during the construction of the Athens Metro, external, but if HS1 is anything to go by, the archaeological considerations could still be huge.

Before any construction work could begin, archaeologists employed by the Channel Tunnel Rail Link project were charged with investigating areas of Kent, Essex and London. More than 40 excavations were carried out along a 46km stretch, and key discoveries included a Neolithic long house in Kent, a Romano-British villa and two Anglo-Saxon cemeteries.

A vast archive of archaeological data was also established.

Specialist archaeological teams will most likely be employed for the HS2 project, and English Heritage says it is continuing to "advise on the proper assessment of the impact [on listed buildings, scheduled monuments and registered parks etc] of the proposed lines so that Parliament can take an informed decision when the Bill is published".

10. Regeneration

This isn't just a railway. It's also effectively a massive regeneration project. That element also takes time.

Toton - proposed site of one of HS2's new stations

The wisdom of spending £32bn to cut an hour or so off journey times has been questioned by some. Justification for the huge expenditure is that it will combat the North-South divide.

"High speed will bring cities in the North and Midlands closer together, so we can really start rivalling London for jobs," Mike Blackburn, chairman of Greater Manchester local enterprise partnership told the Financial Times, external. But delivering regeneration in practice will require planning and ingenuity.

11. Parliamentary approval

Getting anything through Parliament isn't an overnight process.

The bill for phase one is expected to go to Parliament at the end of 2013 and receive Royal Assent in 2015. It is a hybrid bill, which means it is debated by both houses and goes through a longer parliamentary process than public bills. These hybrid bills are allowed to roll over into a new parliament.

Phase two will go to Parliament in 2018 and is hoped to win approval by 2020. Ruse says that there are profound differences between the Channel Tunnel and the new line.

"We were very fortunate there was complete political consensus." It went through on its first reading. However, with HS2, there are a number of coalition MPs, whose constituencies the line passes through, campaigning against it.

"There is considerable opposition to HS2, more in the Conservative Party. It may be the bill doesn't go through on its first reading," says Ruse.

12. Ecology

Any major infrastructure project must protect the environment.

County wildlife trusts are concerned that the proposed route of the first section will pose a threat to wildlife. They estimate more than 150 nature sites could be affected, including 10 Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Four nature reserves will be directly impacted, they say, and more than 50 ancient woodlands lie in the route.

Protected species - such as great crested newts - can create a major stumbling block to any development project.

Bechstein's bat - a rare species whose habitat could be threatened by HS2

For example, one dual carriageway project in Cambridgeshire was delayed when £1m tunnels had to be built to enable an estimated 30,000 newts to safely cross the road. According to the contractors, it took 18 months to get the necessary licence to clear the area of newts and water voles.

A significant population of rare Bechstein's bats, external - which are strictly protected under UK and European law - has already been discovered in Buckinghamshire, in ancient woodland either side of the proposed HS2 route.

13. Bridges

As a rule of thumb, building road bridges costs 10 times as much as putting road on the flat. The same impact on cost and time is there when building railway bridges. The Channel Tunnel rail link involved building the longest high speed viaduct in the world across the Medway. And high speed rail lines require lots of road bridges as there are not level crossings.

14. Franchising and timetabling

One of the advantages of the length of time construction will take is that it gives a long window for setting up and doling out the franchises. The decision over which operator should be granted the franchise can be controversial, as with the government's recent U-turn over the West Coast Mainline. With journey times slashed, the high speed lines will be much sought after by the train operating companies. Once the franchise is agreed, the painstaking work of coming up with a timetable can begin.

15. The UK isn't China

The same project in China might have moved quicker. The 1,318km Beijing-Shanghai high-speed route went from design to completion in 39 months.

But quickly forcing through such a scheme would be unthinkable in a democracy like the UK. David Cameron alluded to the point in an interview this week: "It's difficult to get things built in a modern industrial democracy like Britain - that's why we need to get going now."

As Alan Stilwell, transport expert at the Institution of Civil Engineers, says: "We want to make sure people are properly consulted. But it does involve a longer timescale than in other parts of the world."

16. Local campaigners

Campaigners in the Chilterns have already forced more tunnels to be inserted into the plans. With Chancellor George Osborne's constituency of Tatton being bisected by the new line, intense pressure from local campaigners is likely. The same thing happened with HS1 when campaigners accused the route of threatening Kent's garden of England.

A protestor in Knutsford

17. Moving the dead

There have always been developments that have touched formerly consecrated ground, and the HS2 rail line is no exception. The route is expected to run straight through old cemeteries in London and Birmingham, affecting an estimated 50,000 bodies.

Strict rules apply to the exhumation of bodies. In England and Wales, the Ministry of Justice first has to grant a licence for their removal, it then has to gain planning permission and adhere to rules set out by organisations such as English Heritage and the church.

Reburial must also take place - usually in other nearby cemeteries, and efforts need to be made to contact relatives and inform them of disturbance. In London, the burial grounds are, according to HS2, disused, with no bodies having been interred in a century.

18. Contingency

The route hasn't been finalised. Modelling the programme of works means that contingency time or wriggle room has to be built in for unforeseen problems. Sometimes, as with Wembley Stadium, the contingency period is not sufficiently long for the mishaps that strike, external. It was supposed to open in the middle of 2005. It opened in March 2007.

19. Health and safety

In previous centuries, it was a given that large numbers of people might die building big projects. During the construction of Brooklyn Bridge, opened in 1883, 27 people died. Nowadays there is more care taken over the safety of workers.

But the risks, despite painstaking care, remain high. Ten workers died during the construction of the Channel tunnel between 1987 and 1993.

20. Laying the rails

Once everything is prepared the track can be laid fairly fast. A factory train moves up the line laying track, putting down sleepers and erecting overhead wires, says Roger Ford, technology editor at Modern Railways. "They can probably do about a mile of track a day," he estimates.

Even after the line is finished there needs to be testing to see it works. Months of it.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external