Talk to Frank: Do anti-drugs adverts work?

- Published

Talk to Frank is the longest running anti-drugs campaign the UK has had. But has it stopped anyone taking drugs?

Ten years ago a police Swat team crashed into a quiet suburban kitchen and changed the face of drugs education in the UK forever.

Out went grim warnings of how drugs could "screw you up" and earnest exhortations to resist the sinister pushers lurking in every playground. In came surreal humour and a light, even playful approach.

In the first ad, currently being repeated to mark the 10th anniversary of the campaign, a teenage boy calls in a police snatch squad to arrest his mother when she suggests they have a quiet chat about drugs.

The message was new too: "Drugs are illegal. Talking about them isn't. So Talk to Frank."

Dreamed up by ad agency Mother, Frank was, in fact, the new name for the National Drugs Helpline.

It was meant to be a trusted "older brother" figure that young people could turn to for advice about illicit substances.

Everything from the adventures of Pablo the canine drugs mule to a tour round a brain warehouse has been presented under the Frank label, making it a familiar brand name among the nation's youth.

Crucially, Frank was never seen in the flesh, so could never be the target of mockery for wearing the wrong trainers or trying to be "down with the kids," says Justin Tindall, creative director of ad agency Leo Burnett. Even the spoof Frank videos on YouTube are relatively respectful.

There is also no indication that Frank is an agent of the government - something that makes it rare in the annals of government-funded campaigns.

Drugs education has come a long way since Nancy Reagan - and, in the UK. the cast of Grange Hill - urged teenagers to Just Say No to drugs, a campaign which many experts now believe was counterproductive.

Most ads in Europe now focus, like Frank, on trying to give impartial information to help young people make their own decisions.

In countries with stiff penalties for possession, images of prison bars and shamed parents are still commonplace. One recent campaign in Singapore told young clubbers: "You play, you pay."

In the US, the federal government has spent millions on Above the Influence, external, a long-running campaign that encourages positive alternatives to drug use using a mix of humour and cautionary tales. The emphasis is on talking to young people in their own language - one ad shows a gang of "stoners" marooned on a sofa.

But a surprising number of anti-drugs campaigns around the world still fall back on scare tactics and, in particular, the drug-fuelled "descent into hell".

A typical example is a recent Canadian commercial, external, part of the DrugsNot4Me series, which shows an attractive, confident young woman's transformation into a shivering, hollow-eyed wreck at the hands of "drugs".

Research into a US anti-drugs campaign, external between 1999 and 2004 suggests ads showing the negative effects of drug abuse can often encourage young people "on the margins of society" to experiment with drugs.

Frank broke new ground - and was much criticised by opposition Conservative politicians at the time - for daring to suggest that drugs might offer highs as well as lows.

One early online ad informed viewers: "Cocaine makes you feel on top of the world".

It was not always easy to get the balance of the message right. The man behind the cocaine ad, Matt Powell, then creative director of digital agency Profero, now believes he overestimated the attention span of the average web browser.

Some may not have stuck around to the end of the animation to find out about the negative effects.

But Powell says the aim was to be more honest with young people about drugs, in order to establish the credibility of the Frank brand.

The Home Office says 67% of young people in a survey said they would turn to Frank if they needed drugs advice. 225,892 calls were made to the Frank helpline and 3,341,777 visits to the website in 2011/12.

It's proof, it argues, that the approach works.

But like every other anti-drugs media campaign in the world, there is no evidence Frank has stopped people taking drugs.

Drug use in the UK has gone down by 9% in the decade since the campaign launched, but experts say much of this is down to a decline in cannabis use, possibly linked to changing attitudes towards smoking tobacco among young people.

What little research there is into the effect of anti-drugs campaigns around the world, such as a 2011 study in Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, suggests they have little or no impact on consumption.

"All the research suggests they don't work. They are not cost-effective," says drug prevention expert Prof Harry Sumnall, of Liverpool John Moores University's Centre for Public Health.

Like most people working in the drugs prevention field in the UK he is reluctant to criticise Frank, which is seen as a big improvement on what went before, but adds: "My personal view is that we have tended to rely on Frank as a replacement for a comprehensive drug education strategy."

Mike Linnell of Manchester-based harm reduction charity Lifeline, believes the campaign may have run its course and the money would be better spent on drugs education at a grassroots level.

"The ads certainly haven't got any credibility among serious drug users but I don't think they are aiming for that," he says.

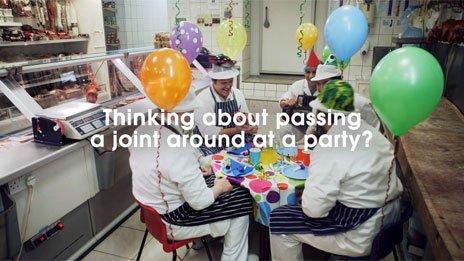

Frank's new campaign features butchers passing around a joint of meat

Part of the problem, he argues, is that the commercials have become too surreal and confusing. He describes the new campaign - featuring a gang of tipsy-looking butchers passing around a "joint" of meat - as "embarrassingly bad".

It is not a view shared by the Home Office, which commissioned them.

"Frank has never used humour just for laughs and it is has always been used to make a serious point. All Frank campaign ideas are tested using focus groups of young people," says a spokesman.

But the biggest challenge facing Frank, according to experts, is the growth of legal highs and so-called "party drugs", now used in the UK by as many as a million young people, according to research by Lifeline.

Stimulants such as mephedrone, thought to be responsible for 29 deaths, have been outlawed but new legal highs, with exotic-sounding names, are being created all the time.

Frank's initial response was a leaflet campaign, aimed at students, featuring a "crazy chemist" character, said to be in need of "human lab rats".

It was described by drugs charity Release as being as simplistic and wrong-headed as the film Reefer Madness or the infamous "Heroin Screws You Up" imagery of the 1980s. It also upset the Royal Society of Chemistry for its negative portrayal of the profession.

Martin Barnes of Drugscope, the body representing most drugs charities in the UK, agrees that the crazy chemist campaign's message - "just because something is legal does not mean it is safe" - was simplistic but, he argues, such an approach might be necessary at this stage.

Like most people in the field, he is glad Frank is still there after 10 years, but worries that it is being used as a visible, easy win by politicians at a time when "education and prevention have slipped down the agenda" thanks to budget cuts.

The Home Office argues that advertising is the most cost efficient method of raising awareness among "a large audience of four million 13-18 year-olds" and correcting the distorted information they get about drugs from popular culture and their peers.

Frank has survived a major cutback in government-funded advertising and, as long as illegal drug use is falling, looks set to be around for a while yet, whether it is responsible for that decline or not.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external