Manx: Bringing a language back from the dead

- Published

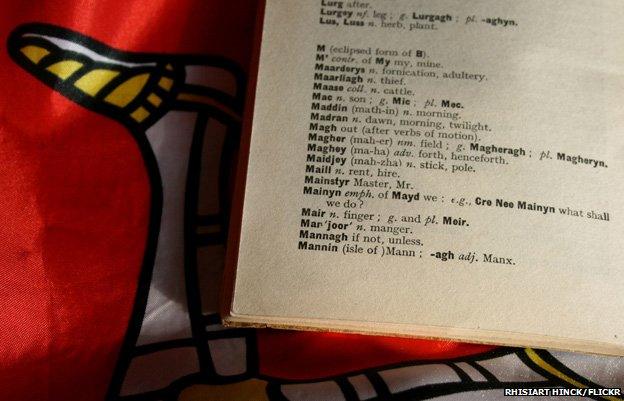

A Manx dictionary on the Isle of Man flag

Condemned as a dead language, Manx - the native language of the Isle of Man - is staging an extraordinary renaissance, writes Rob Crossan.

Road signs, radio shows, mobile phone apps, novels - take a drive around the Isle of Man today and the local language is prominent.

But just 50 years ago Manx seemed to be on the point of extinction.

"If you spoke Manx in a pub on the island in the 1960s, it was considered provocative and you were likely to find yourself in a brawl," recalls Brian Stowell, a 76-year-old islander who has penned a Manx-language novel, The Vampire Murders, and presents a radio show on Manx Radio promoting the language every Sunday.

The language itself has similarities with the Gaelic tongues spoken in the island's neighbours, Ireland and Scotland. A century ago, "Moghrey mie" would have been commonly heard instead of good morning on the island.

Watch: Inside the Isle of Man school where children are taught in Manx

"In the 1860s there were thousands of Manx people who couldn't speak English," says Stowell. "But barely a century later it was considered to be so backwards to speak the language that there were stories of Manx speakers getting stones thrown at them in the towns.

"I learnt it myself from one of the last surviving native speakers back in the 1950s."

Recession in the mid 19th Century forced many Manx residents to leave the island to seek work in England. And there was a reluctance among parents to pass the language down through the generations, with many believing that to have Manx as a first language would stifle job opportunities overseas.

There was a decline in the language. By the early 1960s there were perhaps as few as 200 who were conversant in the tongue. The last native speaker, Ned Maddrell, died in 1974.

The decline was so dramatic that Unesco pronounced the language extinct in the 1990s, external.

But the grim prognosis coincided with a massive effort at revival. Spearheaded by activists like Stowell and driven by lottery funding and a sizeable contribution (currently £100,000 a year) from the Manx government, the last 20 years have had a huge impact.

Now there is even a Manx language primary school in which all subjects are taught in the language, with more than 60 bilingual pupils attending. Manx is taught in a less comprehensive way in other schools across the island.

In an island where 53% of the population were born abroad, it's perhaps surprising that there seems to be as much enthusiasm among British immigrants for Manx language as there is among native Manx people.

"These days it's actually come-overs' like me [the local term for people who have come to the island from other parts of the British Isles] who have more interest in Manx than the locals," says Rik Clixby, a music blogger who moved to the island a decade ago from Middlesbrough in order to marry his university sweetheart.

"It's never going to be at the point where you will hear a whole pub full of people talking in Manx," says Clixby. "But it's becoming more high profile. I'm really interested in learning the language and it's good to see articles now being written in Manx in the local newspapers - not that I can understand more than a few words.

"But it seems to be more of a passion among people who have come here from elsewhere. 'Come-overs' like me are looking for a cultural identity and, now they've found one here, are particularly attached to it."

Donna Long, a lifelong resident of the island, has four sons who all attend the Manx-language school. She thinks that having her children learn Manx as well as English is a hugely positive experience for them.

"Our friends think that it's a slightly eccentric decision to send all our boys there but they all really enjoy it," she says.

"The best thing is that it will hopefully unlock their brain to learn other languages easily too. They were all completely bilingual in Manx and English by the age of six.

"I don't think Manx will ever be useful outside of the island but I certainly think that in terms of getting jobs, if they do stay on the island - particularly in the public sector - then attending this little jewel of a school and being fluent in Manx can never be a disadvantage."

Douglas, the Isle of Man capital

Outside of the strenuous efforts being made in the education, there is also the inevitable app for grown-ups.

There have been 1,700 downloads, including 150 in America, says Adrian Cain, language development officer at the Manx Heritage Foundation. "About 1,900 people at the moment claim to be able to speak Manx, though it's still hard to know the exact levels of fluency."

But the investment in keeping Manx alive doesn't appeal to everyone, Stowell admits.

"If you hear criticism of Manx, it's nearly always from elderly Manx people who still have the mentality of the mid-20th Century when the language was considered to be a totally backward thing to be heard speaking."

Jim Watterson, an Isle of Man resident from Port Erin, is a vocal critic of the money being spent. "Support in this area must be considered carefully and in perspective at a time when education is under such budgetary stress - libraries and pre-schools closing, teacher numbers being cut.

"I would suggest that this level of funding for the teaching of an almost dead language is a luxury that cannot presently be afforded."

But is this Manx language renaissance a prelude to a fully fledged reassertion of patriotism? Stowell doubts it very much.

"I don't think it's a nationalistic thing at all really. We're a wealthy island and we actually aren't part of the United Kingdom anyway. It's not an aggressive bone of contention at all. The island just doesn't work that way.

"Our Latin motto on the national coat of arms says 'Quocunque Jeceris Stabit', which means, 'whichever way you throw it, it will stand' - which says a lot about the stoicism and pragmatism of people here."

On an island with such a large migrant population, albeit mostly British, there has been a heartening turn of events for those who want to preserve languages.

"Nobody on the Isle of Man is much impressed or surprised by anything,", says Stowell. "But it's definitely a positive sign when you can speak our native language in a pub and not get in a brawl - that to me has to be a sign of progress."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external