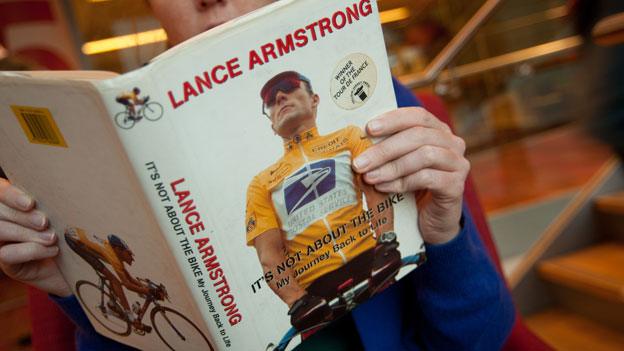

Should buyers of Lance Armstrong's books get a refund?

- Published

Disgruntled purchasers of disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong's autobiography are demanding a refund in the courts. Are they really entitled to their money back?

It wasn't about the bike, after all.

It was about the drugs, the lies and the remorseless smears levelled at anyone who dared stand up to Lance Armstrong.

The cyclist's televised confession that he cheated his way to seven Tour de France victories between 1999 and 2005 rendered his two autobiographies - It's Not About the Bike: My Journey Back to Life (2000) and sequel Every Second Counts (2003) - hollow and fraudulent.

The admission shattered the faith of millions, and now readers who bought into Armstrong's inspiring fabrications - about his fightback from cancer to sporting triumph through honest hard work - are seeking compensation.

Two Californians have filed a class-action lawsuit against the cyclist and his publishers Penguin and Random House - on behalf of themselves and other residents of California who bought the books - demanding refunds and other costs.

BBC 5 live spoke to a man who bought 7,000 Lance Armstrong DVDs

Political consultant Rob Stutzman and chef Jonathan Wheeler would not have spent money on the titles, according to their submission, external, had they known "the true facts concerning Armstrong's misconduct and his admitted involvement in a sports doping scandal that has led to his recent and ignominious public exposure".

In both books, Armstrong is emphatic that the drug charges against him are false.

"Our team had 'zero tolerance' for any form of doping," runs one passage in Every Second Counts. "It sounded like the usual cliched statement, but we meant it. We were absolutely innocent."

Wheeler and Stutzman, a former deputy chief of staff to California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, were not the only ones taken in. It's Not About The Bike alone is reported to have sold more than a million copies.

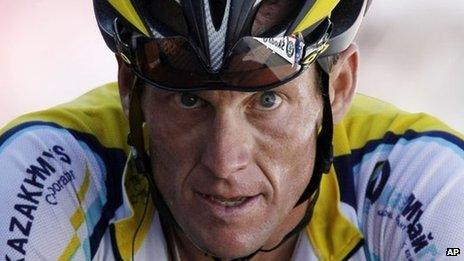

In October 2012, however, a US Anti-Doping Agency report concluded that Armstrong had been a "serial cheat". And earlier this month the 41-year-old confessed to chat show host Oprah Winfrey that he had used performance-enhancing drugs to achieve each of his seven Tour de France victories.

Soon afterwards, a spoof sign in Manly library in Sydney, Australia, promising to reshelve Armstrong's books in the fiction section, was greeted with widespread online approval when a photo of it was shared on social media.

It's no surprise that the response in the US extends beyond satirical pranks, to litigation.

Armstrong's titles are only the latest in a series of series of books which have faced legal action as a result of passages which turned out to be false.

In 2006, author James Frey was sued by readers and his publisher after admitting he had "embellished" his addiction recovery memoir A Million Little Pieces.

Frey and Random House agreed a payout of $2.35m (£1.49m). The publisher agreed to pay court fees, donate to charity and refund readers who purchased the book before news broke that it contained inaccuracies.

However, according to investigative journalism website The Smoking Gun, external, only 1,345 of the four million people who bought the memoir actually got round to asking for their money back ahead of the deadline.

A similar lawsuit filed in 2011 against author Greg Mortenson - which accused him of fabricating much of his book Three Cups of Tea, about a mission to build schools across Central Asia - was dismissed by a Montana judge.

Lawyers for Penguin have said the Armstrong case should be thrown out.

But according to Oliver Herzfeld, who specialises in intellectual property law as chief legal officer at brand licensing agency Beanstalk, the most likely scenario is that Penguin and Random House - not Armstrong himself - will settle out of court.

"I think they'd want to avoid any kind of legal precedent being set," he says.

Millions took inspiration from Armstrong's fake achievements

In their legal submission, the plaintiffs say they suffered "monetary injury" and should be compensated.

"Although Stutzman does not buy or read many books, he found Armstrong's book incredibly compelling and recommended the book to several friends," it reads.

California's consumer protection laws are tight by American standards, Herzfeld says. But it's possible that buyers of the books in other US states, or in other countries, will watch the case closely, and consider launching their own lawsuits.

Not all those taken in by the Armstrong myth believe they are entitled to a refund, however.

A keen endurance mountain bike racer before he was struck by lymphoma, Richard Salisbury was inspired to return to the saddle after reading It's Not About The Bike during his recovery in 2002.

Essentially, he believes, readers of Armstrong's books got what they paid for - and reclaiming the autobiographies' cover price will not retrospectively make up for Armstrong's behaviour.

"The books did help a lot of people through a dark time," he adds.

"Someone gave me the book while I was in remission and it came at the right time. It inspired me to get back out there. You can't take that away."

Richard, a sports rehabilitation specialist in Manchester, who now looks back with bitterness at how "gullible" he must have seemed, believes Armstrong owes the plaintiffs a moral debt rather than a financial one.

"I can understand them taking action, but I don't think they've got anything to go on," he says.

Readers seeking to recoup the cost of a couple of paperbacks represent small beer compared to other organisations who have said they will pursue him:

The Sunday Times, which was forced into an out-of-court settlement in 2004 after Armstrong sued over articles questioning his integrity, is seeking around $1.5m (£945,000)

Dallas-based SCA Promotions, is looking to recover $12.5m (£7.8m) in bonus payments made to Armstrong for his Tour de France wins

The International Cycling Union wants back $4m (£2.5m) in prize money

Nonetheless, it is likely that the legal action will be watched closely by the publishing industry.

The potential ramifications are depressing, believes Jamie Byng, managing director of Canongate books - which famously published the "unauthorised autobiography" of Julian Assange after a dispute with the Wikileaks founder.

He agrees that publishers should try to ensure the integrity of non-fiction books, but insists that an autobiography will never be an impartial account of events.

Similarly, he argues, readers have an obligation to use their own critical faculties. Claims about Armstrong's doping had circulated for years, Byng says. The public, he insists, were free to make up their own minds.

"It's laughable that someone is seriously thinking about doing this," he adds.

"The idea that just because someone calls something a memoir it's definitely the truth is so naive. Every narrator is unreliable.

"Armstrong is a total piece of work and I'm not trying to defend him, but this wasn't the first time this happened and it won't be the last."

If that's the case, more such lawsuits can be expected - with disgruntled readers seeing the relatively low cost of the books as the only tangible thing they can get back from fallen idols in whom they invested so much.

For those demanding a refund, it's not about the bike. But in a culture which places such faith in celebrities, it's not just about the money either.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external