China's 'leftover women', unmarried at 27

- Published

- comments

Over 27? Unmarried? Female? In China, you could be labelled a "leftover woman" by the state - but some professional Chinese women these days are happy being single.

Huang Yuanyuan is working late at her job in a Beijing radio newsroom. She's also stressing out about the fact that the next day, she'll turn 29.

"Scary. I'm one year older," she says. "I'm nervous."

Why?

"Because I'm still single. I have no boyfriend. I'm under big pressure to get married."

Huang is a confident, personable young woman with a good salary, her own apartment, an MA from one of China's top universities, and a wealth of friends.

Still, she knows that these days, single, urban, educated women like her in China are called "sheng nu" or "leftover women" - and it stings.

Who are you calling "leftover"? Huang Yuanyuan (front) and her colleague Wang Tingting

She feels pressure from her friends and her family, and the message gets hammered in by China's state-run media too.

Even the website of the government's supposedly feminist All-China Women's Federation featured articles about "leftover women" - until enough women complained.

State-run media started using the term "sheng nu" in 2007. That same year the government warned that China's gender imbalance - caused by selective abortions because of the one-child policy - was a serious problem.

National Bureau of Statistics data shows there are now about 20 million more men under 30 than women under 30.

"Ever since 2007, the state media have aggressively disseminated this term in surveys, and news reports, and columns, and cartoons and pictures, basically stigmatising educated women over the age of 27 or 30 who are still single," says Leta Hong-Fincher, an American doing a sociology PhD at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

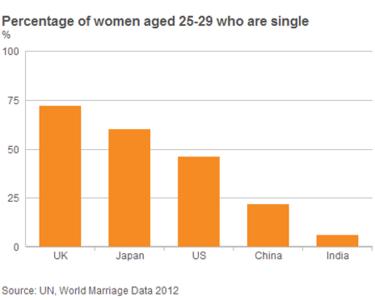

Census figures for China show that around one in five women aged 25-29 is unmarried.

The proportion of unmarried men that age is higher - over a third. But that doesn't mean they will easily match up, since Chinese men tend to "marry down", both in terms of age and educational attainment.

"There is an opinion that A-quality guys will find B-quality women, B-quality guys will find C-quality women, and C-quality men will find D-quality women," says Huang Yuanyuan. "The people left are A-quality women and D-quality men. So if you are a leftover woman, you are A-quality."

But it's the "A-quality" of intelligent and educated women that the government most wants to procreate, according to Leta Hong-Fincher. She cites a statement on population put out by the State Council - China's cabinet - in 2007.

"It said China faced unprecedented population pressures, and that the overall quality of the population is too low, so the country has to upgrade the quality of the population."

Some local governments in China have taken to organising matchmaking events, where educated young women can meet eligible bachelors.

The goal is not only to improve the gene pool, believes Fincher, but to get as many men paired off and tied down in marriage as possible - to reduce, as far as possible, the army of restless, single men who could cause social havoc.

But the tendency to look down on women of a certain age who aren't married isn't exclusively an attitude promoted by the government.

Chen (not her real name), who works for an investment consulting company, knows this all too well.

She's single and enjoying life in Beijing, far away from parents in a conservative southern city who, she says, are ashamed that they have an unmarried 38-year-old daughter.

"They don't want to take me with them to gatherings, because they don't want others to know they have a daughter so old but still not married," she says.

"They're afraid their friends and neighbours will regard me as abnormal. And my parents would also feel they were totally losing face, when their friends all have grandkids already."

Chen's parents have tried setting her up on blind dates. At one point her father threatened to disown her if she wasn't married before the end of the year.

Now they say if she's not going to find a man, she should come back home and live with them.

Chen knows what she wants - someone who is "honest and responsible", and good company, or no-one at all.

Meanwhile, the state-run media keep up a barrage of messages aimed at just this sort of "picky" educated woman.

"Pretty girls do not need a lot of education to marry into a rich and powerful family. But girls with an average or ugly appearance will find it difficult," reads an excerpt from an article titled, Leftover Women Do Not Deserve Our Sympathy, posted on the website of the All-China Federation of Women in March 2011.

It continues: "These girls hope to further their education in order to increase their competitiveness. The tragedy is, they don't realise that as women age, they are worth less and less. So by the time they get their MA or PhD, they are already old - like yellowed pearls."

Ouch.

The All-China Federation of Women used to have more than 15 articles on its website on the subject of "leftover women" - offering tips on how to stand out from a crowd, matchmaking advice, and even a psychological analysis of why a woman would want to marry late.

In the last few months, it has dropped the term from its website, and now refers to "old" unmarried women (which it classes as over 27, or sometimes over 30), but the expression remains widely used elsewhere.

"It's caught on like a fad, but it belittles older, unmarried women - so the media should stop using this term, and should instead respect women's human rights," says Fan Aiguo, secretary general of the China Association of Marriage and Family Studies, an independent group that is part of the All-China Federation of Women.

If it sounds odd to call women "leftover" at 27 or 30, China has a long tradition of women marrying young. But the age of marriage has been rising, as it often does in places where women become more educated.

In 1950, the average age for urban Chinese women to marry for the first time was just under 20. By the 1980s it was 25, and now it's... about 27.

A 29-year-old marketing executive, who uses the English name Elissa, says being single at her age isn't half bad.

Being single is not so bad, Elissa tells Mary Kay Magistad

"Living alone, I can do whatever I like. I can hang out with my good friends whenever I like," she says. "I love my job, and I can do a lot of stuff all by myself - like reading, like going to theatres.

"I have many single friends around me, so we can spend a lot of time together."

Sure, she says, during a hurried lunch break, her parents would like her to find someone, and she has gone on a few blind dates, for their sake. But, she says, they've been a "disaster".

"I didn't do these things because I wanted to, but because my parents wanted it, and I wanted them to stop worrying. But I don't believe in the blind dates. How can you get to know a person in this way?"

Elissa says she'd love to meet the right man, but it will happen when it happens. Meanwhile, life is good - and she has to get back to work.

Mary Kay Magistad is the East Asia correspondent for The World, external - a co-production of the BBC World Service, PRI, external and WGBH, external

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

- Published22 September 2015