Switzerland guns: Living with firearms the Swiss way

- Published

Switzerland has one of the highest rates of gun ownership in the world, but little gun-related street crime - so some opponents of gun control hail it as a place where firearms play a positive role in society. However, Swiss gun culture is unique, and guns are more tightly regulated than many assume.

Throughout the attack, Anne Ithen kept her eyes shut.

"I didn't want to see it. I didn't want those images in my head for the rest of my life... but I remember everything, every detail," she tells me. "Ninety bullets were fired and of course there was the homemade bomb - there was a hell of a noise."

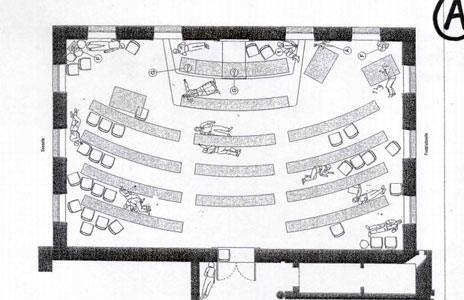

She drops her head slightly as she takes herself back to the Zug cantonal assembly chamber on the afternoon of 27 September 2001, where she was chairing the council meeting. She remembers hearing a loud bang and thinking briefly that someone had accidentally upturned the coffee table in the corridor.

Then the door burst open and she saw Freidrich Leibacher, a local man, dressed in a police vest and laden with guns.

Anne refused to have a gun in the house, even before the attack

"I knew immediately what was going to happen," she tells me simply.

Leibacher, who had a grudge against the officials of the Zug parliament, shot dead 14 people and injured 18 others before turning the gun on himself.

"All that noise..." says Anne hesitantly with her eyes closed. "And yet so much quiet too, as people hid or pretended to be dead. I remember a silence, and his swearing…and just the noise of his boots pacing around the room."

Anne Ithen was shot three times, in the spine, the thigh and the abdomen.

"I knew I was paralysed," she says factually. "You see I didn't feel the other two shots, but the shot that hit my spinal cord splintered and entered my lungs. I couldn't breathe and really feared I was going to die from suffocation." She gives me a wry, ironic smile. "And then someone shouted, 'It's over!'... whatever that meant."

Anne is now a paraplegic. She lost two-thirds of her stomach, one kidney and much of her large intestine. She has nothing but admiration for the surgical team who managed to save her life.

"They had to be pretty creative," she laughs. "It was hard to put together a functioning body from the bits and pieces that were left."

Leibacher declared a "day of rage" against the Zug assembly

Anne admits that she has always hated guns and when, long before the Zug attack, her partner moved in with her, she told him firmly that his Swiss army gun - which all Swiss men of fighting age are issued with - would not be living with them.

In February 2011, she voted in favour of a referendum motion which called for all militia firearms to be stored in public arsenals and for a national gun registry to be established. But 56.3% of voters were opposed to the idea.

"I think we are too lax with gun laws in Switzerland," she tells me. "I was very disappointed the referendum didn't get a majority... especially as we have seen more shooting recently here."

Last month, in the French-speaking village of Daillon, 100km (62 miles) from Geneva, a psychologically disturbed man opened fire on locals, killing three people and wounding two others. Police had already confiscated weapons from the gunman in 2005, after he had been placed in psychiatric care.

Inevitably, his actions prompted a fresh wave of debate in Switzerland about its relatively liberal gun laws.

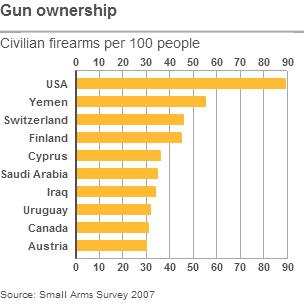

According to the Geneva-based Small Arms Survey, there are about 89 civilian-owned guns for every 100 people who live in the United States. Switzerland ranks third in terms of gun ownership, the Survey estimates, external, with 3.4 million guns among its population of nearly eight million.

Target shooting is a popular national sport but many of the firearms in Switzerland are military weapons.

The Swiss Sports Shooting Association has 175,000 active members

All healthy Swiss men aged between 18 and 34 are obliged to do military service and all are issued with assault rifles or pistols which they are supposed to keep at home.

Twenty years ago the Swiss militia was a sizeable force of around 600,000 soldiers. Today it is only a third of that size but until recently most former soldiers used to keep their guns after they had completed their military duties, leading to lots of weapons being stored in the attics or cupboards of private Swiss households.

In 2006, the champion Swiss skier Corrinne Rey-Bellet and her brother were murdered by Corinne's estranged husband, who shot them with his old militia rifle before killing himself.

Since that incident, gun laws concerning army weapons have tightened. Although it is still possible for a former soldier to buy his firearm after he finishes military service, he must provide a justification for keeping the weapon and apply for a permit.

When I meet Mathias, a PhD student and serving officer, at his apartment in a snowy suburb of Zurich, I realise the rules have got stricter than I imagined. Mathias keeps his army pistol in the guest room of his home, in a desk drawer hidden under the printer paper. It is a condition of the interview that I don't give his surname or hint at his address.

"I do as the army advises and I keep the barrel separately from my pistol," he explains seriously. "I keep the barrel in the basement so if anyone breaks into my apartment and finds the gun, it's useless to them."

He shakes out the gun holster. "And we don't get bullets any more," he adds. "The Army doesn't give ammunition now - it's all kept in a central arsenal." This measure was introduced by Switzerland's Federal Council in 2007.

Mathias carefully puts away his pistol and shakes his head firmly when I ask him if he feels safer having a gun at home, explaining that even if he had ammunition, he would not be allowed to use it against an intruder.

"The gun is not given to me to protect me or my family," he says. "I have been given this gun by my country to serve my country - and for me it is an honour to take care of it. I think it is a good thing for the state to give this responsibility to people."

Women's magazine Annabelle launched a gun control campaign in 2006

In America then, gun ownership is about self-defence whereas in Switzerland it is seen more in terms of national security. To many traditionalists, a gun in the home has become a metaphor for an independent, well-fortified Switzerland which has helped to keep the country out of two world wars.

Hermann Suter, vice-president of the Swiss lobbying group Pro Tell, is infuriated by calls that the Swiss military should give up their guns and store them in a central arsenal.

"It is a question of trust between the state and the citizen. The citizen is not just a citizen, he is also a soldier, " he reminds me. "The gun at home is the best way to avoid dictatorships - only dictators take arms away from the citizens."

We discuss the recent shootings in Daillon, and I ask him whether he is concerned that each of Switzerland's 26 cantons have gun registers but do not share their data nationally. Under such a system isn't it feasible, I ask, that I could be refused a licence to buy a gun in the canton of Vaud and yet could hop on the train to nearby Valais and buy one there without anyone knowing I had been refused a permit a few miles down the road?

"There is a lack there," admits Mr Suter. "The systems are not connected. But today they are really on their way to fitting all the information together, and there is not a single legal gun here which is unregistered. But a national register does not necessarily avoid tragedy - 100% control you cannot organise. It's impossible."

Yet despite the prevalence of firearms, violent gun-related street crime is extremely rare in Switzerland.

The Swiss army SG550 assault rifle has been used in many suicides, as well as the Zug massacre

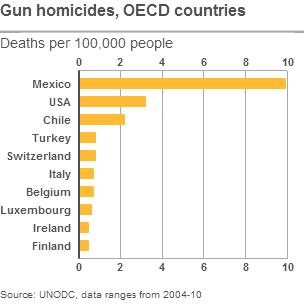

In an average year here, there is one gun murder for every 200,000 of the population - in the US that figure is several times higher. But there are more domestic homicides and suicides with a firearm in Switzerland than pretty much anywhere else in Europe except Finland.

In his office at Zurich University, Professor Martin Killias, director of criminology at Zurich University is flicking through research papers about gun-related homicides.

"It's like smoking. Less is more. I don't support outlawing guns, I recognise people have their hobbies, just as I have mine," he tells me.

"But the fewer guns there are in cellars, attics and armoires, then that would be helpful, because there is a strong correlation between guns kept in private homes and incidences occurring at home - like private disputes involving the husband shooting the wife and maybe the children, and then committing suicide."

Prof Killias was a supporter of the 2011 referendum initiative to keep all militia firearms in a central arsenal - because, he says, of the evidence provided by recent statistics.

"Forty-three per cent of homicides are domestic related and 90% of those homicides are carried out with guns," he says.

"But over the last 20 years, now that the majority of soldiers don't have ammunition at home, we have seen a decrease in gun violence and a dramatic decrease in gun-related suicides. Today we see maybe 200 gun suicides per year and it used to be 400, 20 years ago. "

The army is not the only entity to have a tradition with guns however. About 600,000 Swiss - many of them children - belong to shooting clubs.

On the second weekend in September each year, about 4,000 Zurich girls and boys, aged 12 to 16, take part in Knabenschiessen, a rifle marksmanship contest. The winner is honoured with the title King of the Marksmen.

"Never point your gun anywhere but the target or the ceiling," instructor Michael Merki warns me as he gives me my first air rifle lesson at a Zurich shooting range. "Safety must come first." He steadies my hand.

It has taken a good five minutes to unpack Michael's guns. I count four padlocks on his carrying case.

Civilians trained to fight helped keep Switzerland out of two world wars

"Shooting instructors at rifle clubs always control who is shooting," he says. And all ammunition bought at the club has to be used there.

"When the shooting is finished and the person wants to leave the club, the instructor will look to see how many bullets have been shot and will demand the rest are given back."

He loads my rifle and, reluctantly, I shoot twice at the target - the first shots I've ever fired in my life.

When I see I've scored highly with a very accurate shot, I feel an electric frisson of excitement go through my body. I wonder how children manage that sense of thrill, and suggest that perhaps gun clubs glorify weapons and encourage an unhealthy fascination with guns?

A murmur of protest is heard around the rifle club.

"It teaches people to respect guns," Michael tells me. "A lot of hyperactive children come to rifle club. They learn to stand still, to concentrate for much longer, and it helps them get better results in school, and in life."

Swiss citizens - for example hunters, or those who shoot as a sport - can get a permit to buy guns and ammunition, unless they have a criminal record, or police deem them unsuitable on psychiatric or security grounds. But hunters and sportsmen are greatly outnumbered by those keeping army guns, external - which again illustrates the difference between Switzerland and the US.

Prof Killias cannot hide his anger with those in America who use Switzerland to illustrate their argument that more gun ownership would deter or stop violence.

"We don't have a gun culture!" he snaps, waving his hand dismissively.

"I'm always amazed how the National Rifle Association in America points to Switzerland - they make it sound as if it was part of southern Texas!" he says.

"We have guns at home, but they are kept for peaceful purposes. There is no point taking the gun out of your home in Switzerland because it is illegal to carry a gun in the street. To shoot someone who just looks at you in a funny way - this is not Swiss culture!"

Street violence has gone up in recent years in Switzerland but there hasn't been an increase in gun-related incidents.

That's little comfort, though, to Anne Ithen. She has given up her political career since she was gunned down in the Zug parliament 12 years ago, but she retains strong political opinions.

"I'm not happy about the situation now in Switzerland," she tells me firmly. "The laws have not changed very much, only a tiny, wee bit. It takes just a short moment if a weapon is used to destroy a lot, as you can see with my story, and it takes a very long time to recover and build a new life… and that's a very hard fact to swallow."

She smiles at me kindly. "You ask if I often think about the shooting?" She points down to her wheelchair. "It's always present."

Listen to Emma Jane Kirby's report from Switzerland on BBC Radio 4's Broadcasting House.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external