The heavy metal-loving church

- Published

Many think of church as incense, organ music and dog collars. But there are new churches that look rather different.

Before he was a minister in the Church of England, Mark Broomhead took thrash metal very seriously.

His band, Seventh Angel, toured the world, sharing a record label with heavy metal acts Metallica and Slayer.

Now he is vicar of the Order of the Black Sheep, a church in Chesterfield. It's part of the Church of England, but Broomhead doesn't appear to have mellowed.

"We want it to be as uncomfortable as possible for people who'd go to an ordinary church," he says, speaking about his new ministry.

He is not alone in his endeavour. A number of underground Christian groups are at work across the country, reaching out to people and subcultures that feel alienated by the traditional Church.

As media attention remains focused on the Church of England's stance on issues like women bishops and gay marriage, this very different type of Christian scene has gone largely unnoticed.

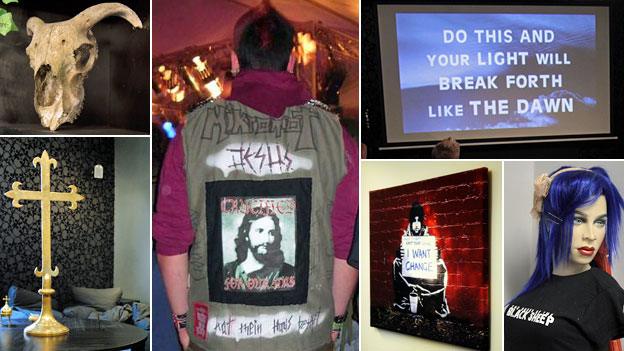

The Order of the Black Sheep meets in Chesterfield

The Order of the Black Sheep is based in a converted beauty salon. The walls are painted black to match its gothic logo, and a ram's skull perches ominously on a bookshelf.

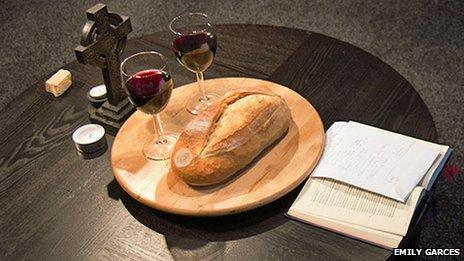

The service itself lasts just a few minutes. A short sermon about Lent is interspersed with film clips and an electro soundtrack. The congregation sink into bean bags instead of filing into pews, and afterwards bread and wine are passed around at leisure. Informality reigns.

Two of its members explain the church's unique appeal: "I was brought up in a charismatic, happy clappy church, and I honestly wish I hadn't been," says Rees Monteiro. "There's no standing around here, listening to someone waffle on."

He shares Broomhead's taste in music too. "I'm into really heavy metal. The more dark and twisted the better."

Karl Thornley brings his children to the services.

"I'm not a very conventional person, and found the traditional Church quite difficult. I think there's a growing disconnect between the Church of England and what people can relate to."

In London, another unusual group meet in the back room of a large Victorian church in Camden. The Glorious Undead are not Anglicans, but they are an official church, part of the Elim Pentecostal network.

One of the group leaders, Andy White, explains that the church had its roots in the metal scene.

"I used to be in a hardcore band back in the day. When the church started it was very much about reaching out to metalheads, but we feel that God's widened that vision for us, so it doesn't revolve around music anymore."

Outside of the church, though, several members are still active in those communities.

Alan Hewlett DJs at Christian metal nights in his spare time, and has strong views about what he will play. "A lot of metal artists are into demonic practices, Satanism and things like that, and I'm not the biggest fan of Satan."

Michael Bryzak plays in Bloodwork, a band he defines as "extreme metal".

"It's a mixture of death and black metal. Anything that sounds distorted and nasty," he says. "We sing about how bad life can be but always make sure there's a bit of hope.

"People at gigs know we're Christian so we do get comments. Someone will shout 'Are you going to play Kumbaya?' but it's usually in good spirit".

Echoing the views of many in the group, Paula Spirandio sees a difference between being Christian and being religious. "I'm totally against religion. To me, it just means tradition and going through the motions."

More radical than either the Glorious Undead or the Order of the Black Sheep is a third organisation known simply as Asylum.

A registered charity, but not a church, the group meets each week in the Intrepid Fox, an alternative rock and metal pub in central London. Also describing themselves as non-religious, they go further and actively reject the structure and hierarchy of the Church.

They have no single leader, or preacher, and share equally in the running of the group.

Britain Stelly, a trustee, says: "You can be honest about anything going on in your life here, having sex, being gay, doing drugs, or even being into vampires. There's no judgement here.

"I want to present faith in more intelligent ways to encourage people to get inspiration and go on their own spiritual journeys."

Just across the road from the Intrepid Fox is St Giles-in-the-Fields, a very traditional Anglican church. Associate Rector Alan Carr is aware of the group, and finds their presence encouraging.

"It's very special work that they do", he says. "Although it's so different, I think we have something in common. I couldn't do it, I'd be hopeless, which is why I'm on this side of the road and not that side."

But there will be more conservative members of the Church who would differ in their assessment. Timothy Edwards, a council member of the evangelical Church Society, questions the message a group like Asylum might be sending.

"We hold very firmly to classical biblical morality on issues of sex and marriage," Edwards says.

"It's brilliant that they want the Church to be open to all sorts of different people, but my question would be 'are they making the challenges of Jesus clear to people?' Like the challenge that sex should only be between one man and one woman for life."

One Asylum member, Catherine Field, recalls her first encounter with the group. "I remember being at Sunday school wearing black lipstick and thinking 'can I still be a Christian and be all the other things I am?', and then I came here and realised that I can."

As well as hosting regular club nights, the non-denominational group do outreach work and try to talk to non-Christians in alternative communities.

Many people in subcultures have been hurt by the insensitive actions of many churches, they say, adding, "We are trying our best to undo some of that damage."

Members of all three groups plan to attend Meltdown, external, a Christian hard music conference held in Wales each year in May. Dave Williams, a pioneer of Christian metal in the UK, organises the event and publishes Detonation magazine.

"Back in the 80s, the Church was afraid of metal culture," he says, and draws a parallel with the US, where the scene is much bigger.

An Asylum meeting: Why should the devil have all the best death metal tunes?

His view is confirmed by Pastor Bob Beeman, who runs Sanctuary International, external from Nashville, Tennessee, a ministry aimed at metal fans.

"A lot of people were getting rejected by the Church, especially in the 80s and early 90s. I didn't want to see that kind of dogma and legalism and so I founded Sanctuary," he says. "Today there are major Christian metal communities in really surprising places, from India to Lebanon. There are literally thousands of bands."

When asked if he would describe the phenomenon as "alternative" Christianity, Beeman sounds unsure.

"To be honest I'm not really in love with that term. I don't think we need an alternative, I think we just need correction."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external