A Point of View: Why does everyone hate Birmingham... even Jane Austen?

- Published

Birmingham bashing has a long tradition dating back to Jane Austen. Unfair, says historian David Cannadine, as he defends his old stomping ground.

It seems that we're in the midst of another round of what might be termed Jane Austen worship, and once again it's to do with her most celebrated novel Pride and Prejudice, though not this time because of Colin Firth as Mr Darcy getting his shirt wet, nor on account of any alleged connection with the zombies, but rather because it's the 200th anniversary of the first publication of the novel in February 1813.

To mark this occasion, a slew of new books is appearing about Jane Austen's life, work and world, and later this month the Royal Mail will issue a series of six commemorative stamps, celebrating all her great novels.

I first became an admirer of Jane Austen when I studied Emma for A-level English literature, and I was so captivated by its wit and warmth, its delicious irony and irrepressible high spirits, that I asked for a single volume edition of her collected works as a school prize.

But although my admiration remains unbounded, I must confess to some slight equivocation, because in the pages of Emma, she offers this damning observation: "Birmingham is not a place to promise much... One has no great hopes of Birmingham. I always say there is something direful in that sound."

To be sure, these are not Austen's own words, but a speech delivered by Mrs Elton, who is a snob, a social climber and an incorrigible name-dropper.

But the England of provincial industrial cities was not exactly Jane Austen territory, and I've never been able to dismiss the uncomfortable thought that this disparaging view of Birmingham may, indeed, have been her own opinion too.

Her words cause me particular concern, not to say pain and anguish, because I myself come from Birmingham, and since I remain strongly attached to the city where I grew up, I cannot share the negative opinion expressed in Emma. Of course, this might be easily dismissed as another example of what could be termed provincial pride and prejudice, but there's also abundant evidence in support of such a contrary view.

Three of the great pioneers of the industrial revolution, James Watt, Matthew Boulton and William Murdoch, did their most important work in Birmingham and at just the time when Austen was writing. Two of Britain's most significant 19th Century politicians, John Bright and Joseph Chamberlain, were sustained in their public careers by the support of the Birmingham electorate.

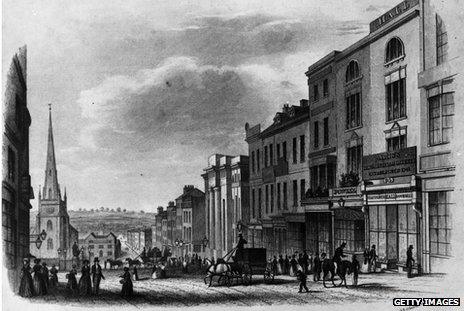

The city several decades after Austen's time

More recently, under Simon Rattle, the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra became one of the leading municipal bands in Europe, while the novels of Jonathan Coe give an unforgettable picture of life in the city at just the time when I was growing up there.

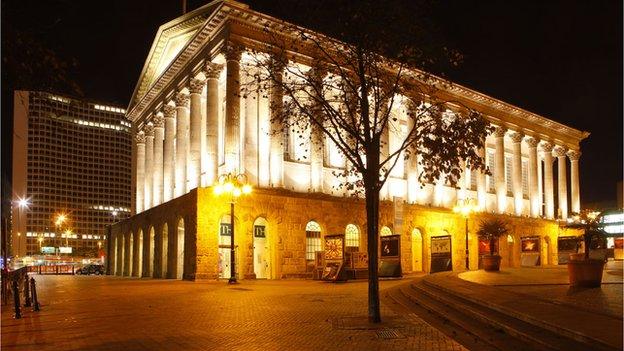

Among the great and the good of Birmingham, one name is especially in evidence this year, and that's Sir Barry Jackson, who was born in 1879 into a rich local family. From an early age, he showed an interest in acting and the theatre, he organised and funded an amateur dramatic group called the Pilgrim Players, and soon after he established the Birmingham Repertory Company.

In 1913, just 100 years ago, Jackson opened his own purpose-built theatre in the centre of the city, ever after known as the Birmingham Rep, with a production of Twelfth Night. From the beginning, the Rep was a pioneering and innovative place. In the first decade, Jackson produced a string of world premieres, and his theatre soon became a forcing house for new acting talent, including such familiar names as Laurence Olivier, Edith Evans, Stewart Grainger and Ralph Richardson.

Barry Jackson died in 1961, but the Rep has remained a place where young actors often serve defining apprenticeships, and one example remains indelibly in my memory. In 1960, or thereabouts, I went with my parents and sister to the Rep's Christmas pantomime, where the male lead was played by a young, charismatic actor, who was diabolically dressed all in black.

Quite by chance, I had myself just played the part of a demon king in a Christmas play at my primary school. But my mother, in the only act of disloyalty I can ever recall, declared the performance of this aspiring thespian to be vastly superior to my own. The scars of this devastating maternal put-down have remained with me to this very day. But since the young actor in question was named Derek Jacobi, I'm grudgingly forced to admit that posterity has amply vindicated my mother's verdict.

In 1971, exactly 10 years after Sir Barry Jackson died, the Rep moved to a new building in a new location that's now known as Centenary Square. Like many regional theatres over the past half century, the Rep has had its ups and downs. But as it prepares to celebrate its 100th anniversary, the mood today is decidedly upbeat. This is partly because of the rich artistic heritage that was bequeathed by Sir Barry Jackson, and partly because of the major refurbishment programme that's presently being undertaken.

Birmingham's futuristic Bullring is a centrepiece of its urban renewal

But it's also because the Rep has become the focal point for a remarkable city centre renaissance and cultural rebirth that's been going on for 20 years, and that is still very much a work in progress. Just along the road from the Rep is Symphony Hall, which the corporation built for Simon Rattle in 1991 as the permanent home of the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, and its acoustics are among the best in the world.

And next to the Rep, a new Library of Birmingham is being constructed which is the largest such project ever undertaken in Britain outside London.

I must declare an interest, because I'm a trustee, and I'm delighted to be associated with this major civic initiative. The new library supersedes an unlovely 1970s structure, designed by the late John Madin, which replaced a fine Victorian building where I fondly remember working as a sixth former and an undergraduate.

Across more than 150 years, a great central library has been an essential feature of Birmingham's community life, as, indeed, of many other towns and cities, yet today, public libraries are threatened from all sides. Central government doesn't seem to be much interested, local authorities are compelled to cut funding, and the IT revolution may portend the end of libraries as we know them.

But there's another way of looking at this because as places where the old and new technologies of knowledge converge, align and complement each other, that are open and welcoming to people of all backgrounds and all ages, and that connect the local and the global, our city libraries remain a vital asset and indispensable resource, as was rightly pointed out last weekend during National Libraries Day.

Like many of our once great industrial centres, Birmingham's economy is less vibrant and varied than it was in the days when it was known as the "city of a thousand trades" and as a result, it's facing some serious social and financial problems. But this new library is an expression of civic confidence - in people, in knowledge, in the region and in the future. It's due to be completed this September, and at the same time, the refurbished Birmingham Repertory Theatre will also be reopened.

Star conductor Simon Rattle in action

Along with the nearby Symphony Hall, the result will be a cluster of buildings dedicated to culture, the arts and education that few cities can match, but that all cities should be able to claim and proud to boast. It's an exhilarating prospect, and not only for its own sake, but also because it provides yet another unanswerable riposte to Mrs Elton's foolish and ignorant claim that "Birmingham is not a place to promise much".

Even as we celebrate Jane Austen once again this year, those are some words of hers that I can never quite forget - and never quite forgive.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external