Italy's 10-metre Alpine mega-tunnel

- Published

Some 10km (six miles) has been dug on the French side

After 20 years' delay because of opposition from locals and environmental campaigners, work on the Italian side of a high-speed rail tunnel designed to link Turin with Lyon in France has finally begun. But with protesters in the woods and hills around the site, the Italian army has been brought in to provide security.

He called my mobile phone sounding a little panicky, shortly before our rendezvous at an anonymous motorway service station in north-west Italy.

"We have to change the plan," he blurted. "They've found out you're coming!"

This sounded interesting. My run-of-the-mill filming trip to a tunnelling project - albeit the world's most extravagant in ambition, budget and controversy - was turning into a scene from a spy drama.

"Who's found out what?" I asked.

"The protesters!" he exclaimed. "We can't meet there after all."

His alarm was understandable. For 20 years, a well-marshalled army of local protesters has successfully resisted grandiose Franco-Italian plans to drill a 57km (35-mile) tunnel through the Alps, and I could not help feeling that perhaps their British counterparts may already be studying their tactics for any guerrilla war they launch against the planned London-to-Birmingham high-speed-rail route.

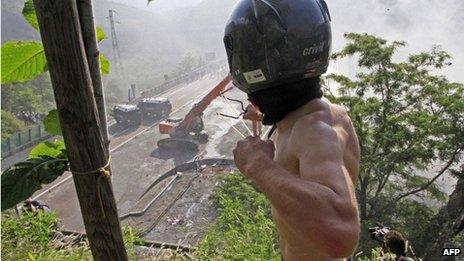

In Italy, they have lobbied tenaciously - and at times violently - in their fight against the rail link between Lyon and Turin. Some 400 people were injured in clashes with the police last year when the tunnel site was first fenced off.

No wonder Francois Pelletier, the palpitating spin-doctor, expected trouble. The protesters had discovered that we were coming to film the Italian bulldozers as they finally began to claw away at the soil of their beloved Susa Valley - and this in the same week that the very future of the gigantic project was called into question by European Union budget cuts.

Sensibly Francois Pelletier directed us instead to rendezvous at a quiet local train station. Only when he was confident that we were who he thought we were, did he emerge.

Our clandestine journey unfolded. We had to follow Francois to the construction site - there are no road signs.

Entering a motorway tunnel in the darkness, we suddenly dived off down an unmarked ramp, past a few traffic cones and emerged into a surreal military zone.

The Italian army has been deployed to keep the site secure.

In March 2012, protesters occupied the highway at nearby Bussoleno

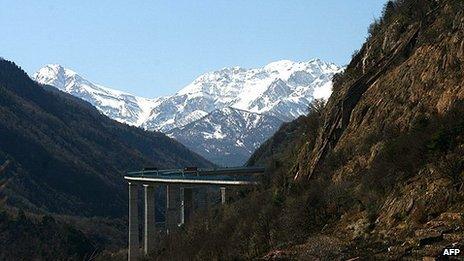

There is clearly embarrassment that - while the French have already drilled and completed 10km (six miles) of exploratory tunnels - on the other side of the border, Italian progress on a five-mile tunnel amounts to a scrape in the mountainside approximately 10m (11 yards) deep - a parking space for a double-decker bus.

Only another 8,036m (five miles) to go, then!

The military operation certainly made for great theatre with camouflaged trucks, towering fences and soldiers patrolling the woods. But the protesters were also enjoying the spectacle as they camped up in the trees, lobbing rocks at bulldozers and filming us as we filmed them.

The protesters are adept at firing slingshots

The EU has backed the tunnel ever since its inception in the early 1990s, but its leaders agreed last week to cut the overall budget for the union for the next six years - and grand infrastructure projects could be vulnerable.

Last year, the French Court of Auditors projected that the final bill for the tunnel would be double the 13bn euros (£11bn/$17bn) envisaged in the 1990s. It would end up costing more than the Channel Tunnel. Nor, concluded the court, was there any certainty that it would ever return a profit.

Yes, it would create 3,550 jobs - but at an average cost of a staggering 3m euros (£2.5m/$4m) per job.

The pro-tunnellers employ a mixture of hyperbole and hard-nosed economic home truths as they argue for the project. The Atlantic will reach out to the Urals via this new link, they cry. Freight trains will zoom to and fro, boosting the shambling economies of southern Europe. Of greater interest to British tourists - skiers like me - is that the journey time from London to Milan will be cut to just six hours.

The naysayers insist that the tunnel will be an ugly, expensive white elephant. They point out that the existing trans-Alpine road and rail routes seem to cope very nicely, thank you. They claim that projections of traffic were drawn up 20 years ago and are hopelessly out-of-date. And they are worried about potentially dangerous minerals that are buried underneath the mountains being released into the air and water.

Hand on heart, even the keenest of protesters would struggle to claim the Susa Valley was an area of outstanding beauty. A narrow pass, it is already crammed with the clutter of human development - a motorway stalks across the valley floor on gigantic stilts, elevated above railway lines, quarries and factories.

People have tried to cross this valley in all kinds of ways - one of the first was Hannibal, the great warrior-leader of Carthage whose own transalpine adventure ended in Susa in 218BC.

Hannibal's journey across the mountains, with 20,000 soldiers and 37 fighting elephants, took him just 16 days. No-one stood in his way... now, those were the days.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00.

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external