The bug-hunters discovering new species in their spare time

- Published

Everyone knows there are lots of species yet to be discovered in rainforests and remote parts of the world. But hundreds are being discovered every year in Europe too - most of them by amateurs.

"If you want to find something new, you have to go to a place nobody has been before," says Jean-Michel Lemaire.

"You have to open your eyes."

Lemaire is a retired mathematician from south-east France with a passion for beetles.

In the last few years, Lemaire has found seven new species.

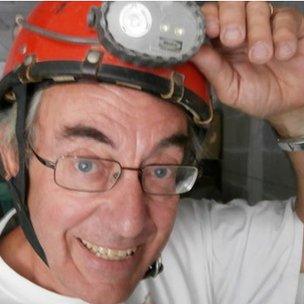

He has hunted them down by exploring caves and crawling through tunnels dating back to the Middle Ages.

It was in one such tunnel in Monaco that he found his most prized discovery - a tiny, blind soil-dwelling beetle.

The Monaco beetle is only 2mm long

Lemaire thinks it probably lives nowhere else on earth but the Rock of Monaco.

"Finding a new species is like the holy grail," he says.

Already about 350,000 beetle species have been identified, making it one of the biggest animal orders on the planet.

A helmet-mounted lamp is key equipment for a beetle-hunter

It is hard work crawling around underground, but, Lemaire points out, beetles are at least easier to catch than some other creatures - butterflies, for example.

For centuries, scientists have catalogued the creatures of Europe - the tall and the small, the feathered and the furred.

After all, Europe was home to some of the most revered naturalists of all time, including Britain's Charles Darwin and Sweden's Carl Linnaeus, the biologist who popularised the Latin naming system for every species on Earth.

And yet "we only know the tip of the iceberg," says ecologist Benoit Fontaine of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris.

"There are more species that we don't know than species that we know."

In Europe alone, about 700 new species are being discovered each year, external, says Fontaine. That's about four times the rate of two centuries ago.

These species tend to be tiny creatures - often insects, spiders, and worms. And many of the animals would likely have remained undiscovered if not for a dedicated band of naturalists who have set out to find new creatures.

New species recently discovered in Europe

This is a new species of spider, Troglocheles lanai, discovered at Mercantour National Park. It's only about 2mm long and lives in caves

Selenochlamys ysbryda, or "ghost slug", was found by a retired man in his back garden in Cardiff and identified by experts at the National Museum Wales. It's a carnivore and is probably blind

This little wasp, Kollasmosoma sentum, was found by a technician in the car park by his office in Madrid, Spain. It hovers at just one cm above ground and feeds on ants

This parasitic wasp, Stibeutes blandi, was discovered up a mountain in Scotland in 2006 by an experienced amateur. It's the only known specimen of its kind and is now kept at the National Museums of Scotland

Uncispio reesi, a marine bristleworm, was found in the southern Irish Sea, off the coast of Anglesey. There are only two other species in the same family - both of which live in North American waters.

One such place where this is happening is Mercantour National Park, at the foot of the Alps on the border between France and Italy. While Jean-Michel Lemaire goes hunting in inaccessible nooks and crannies, there are still plenty of creatures waiting to be found in a more accessible place like this.

"We have a very good knowledge of birds, and mammals" in Mercantour says Marie-France Leccia, an ecologist at the park. "Less for the insects."

Leccia manages a project to look for new insects and other small organisms here.

The park is known as a hotspot of biodiversity. It sits at the intersection of Mediterranean, alpine, and continental climate regions. The rainfall and temperature patterns from these regions converge on the park's undulating landscape, splintering the area into countless tiny habitats.

Species emerged to adapt to these micro-environments. In Mercantour National Park alone, they have found 50 new species in the last six years, including species of centipedes, moths and spiders.

Some of the amateur sleuths are young, some middle-aged, but pensioners are well represented too.

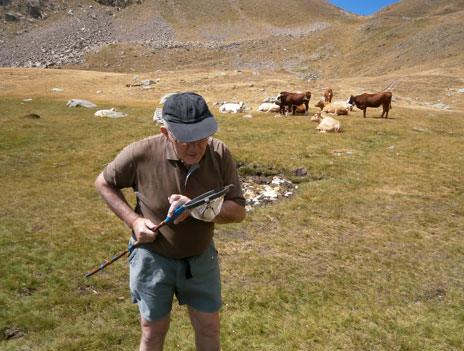

Two of them - Michel Brulin, 63, and Pierre Queney, 73 - crouch beside a creek, scanning for insects, looking like children searching for their next treasure in the water.

Pierre Queney on the hunt for new species in Mercantour

"Marvellous. Extraordinaire!" exclaims Brulin, delighted with the amount of life in the water. "It's a paradise for me."

Brulin, a former biology professor, is one of France's experts on mayflies, and Queney, who used to work in the nuclear power industry, is a specialist in aquatic beetles. And there are many similar groups in other countries fanning out across the continent looking for new animals.

In fact, six out of every 10 of the new species in Europe are discovered by amateurs, often self-taught experts in particular insect and invertebrate families.

New species are sometimes hiding in plain sight - a new species of wasp was recently discovered by a technician in a car park by his office in Spain. And not long ago, a retired man in Wales came across a new type of slug in his back garden.

At the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, ecologist Benoit Fontaine says the search for new species in the Old World does not diminish the need to continue looking in the tropics, where there are also more species to be found.

He says people should be looking everywhere - because extinctions are happening at an unprecedented rate.

"We will need several centuries to describe everything in the world," he says. "And things are disappearing faster than we can discover them. So we should hurry."

Ari Daniel Shapiro was reporting for The World, external and the PBS programme NOVA, external. The World is a co-production of the BBC World Service, PRI, external and WGBH, external

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external