10 things about the conclave

- Published

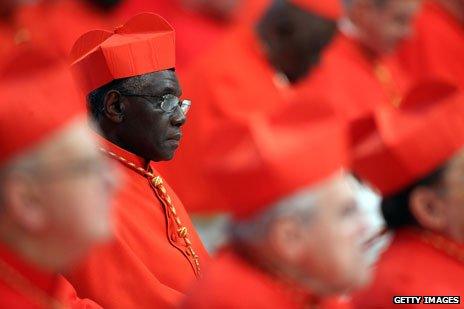

The cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church are gathering to elect a new pope. At some point, white smoke billowing from the Sistine Chapel will show that a decision has been made. But what goes on behind the closed doors before the smoke appears? Here are 10 lesser-known facts about the conclave.

1. It's a lock-in. Conclave comes from the Latin "cum-clave" meaning literally "with key" - the cardinal-electors will be locked in the Sistine Chapel each day until Benedict XVI's successor is chosen. The tradition dates back to 1268, when after nearly three years of deliberation the cardinals had still not agreed on a new pope, prompting the people of Rome to hurry things up by locking them up and cutting their rations. Duly elected, the new pope, Gregory X, ruled that in future cardinals should be sequestered from the start of the conclave.

2. Spying is tricky. During the conclave they are allowed no contact with the outside world - no papers, no TV, no phones, no Twitter. And the world is allowed no contact with them. The threat of excommunication hangs over any cardinal who breaks the rules.

Before the conclave starts, the Sistine Chapel is swept for recording equipment and hidden cameras. It is a myth that a fake floor is laid to cater for anti-bugging devices... Anti-bugging devices are used, and the floor is raised, but only to protect the marble mosaic floor.

3. Portable loos play an essential role. Until 2005, the cardinals endured Spartan conditions in makeshift "cells" close to the Sistine Chapel. They slept on hard beds and were issued with chamber pots. Pope John Paul II changed that with the construction of a five-storey 130-room guest house near St Peter's - Domus Sanctae Marthae (St Martha's House). But cardinals still have to rough it while voting. In an interview with the Catholic News Service last week, Antonio Paolucci, the director of the Vatican Museum said: "I believe they may be installing portable chemical toilets inside the chapel."

One of the world's better furnished polling stations

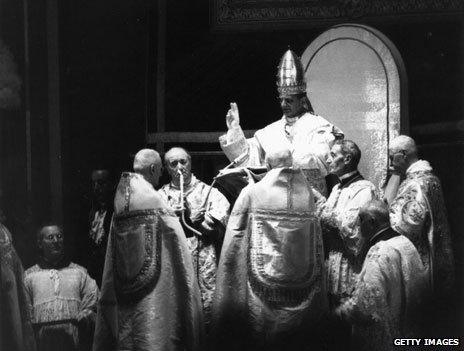

4. An "interregnum" is ending. The pontificate used to be known as a "reign" - hence the period between two popes being called an interregnum ("between reigns"). Many of the regal trappings of the papacy were set aside by Pope Paul VI, who began his pontificate in 1963 with a coronation, but never wore the beehive-shaped papal tiara again.

The last coronation, in 1963 - and the last outing of the crown

5. Counted votes are sewn up. The cardinals hold one vote on day one and then two each morning and afternoon until a candidate wins a two-thirds majority. Each writes his choice on a slip of paper, in disguised handwriting, and folds it in half. Cardinals then process to the altar one by one and place the ballots in an urn. The papers are mixed, counted, opened and scrutinised by three cardinals, the third of whom passes a needle and thread through the counted votes. At the end of each morning and afternoon session the papers are burned.

The Conclave's secrecy means outsiders are left looking for clues in the smoke

6. Chemicals colour the smoke. Those 115 ballot papers produce an unusual amount of smoke... which pours out of a chimney specially installed on the roof of the Sistine Chapel. A chemical is mixed with the paper to produce black smoke when voting is inconclusive, or white smoke when a pope has been elected. But even the white smoke looks dark against a bright sky, so to avoid any possible confusion, white smoke is accompanied by the pealing of bells. In 2005, though, the official responsible for authorising the bells was temporarily occupied with other duties, so there was a period of confusion while white smoke billowed out, and the bells of St Peter's remained silent.

7. Robes are prepared in S, M and L. The Pope has to look the part when he is presented to the faithful from a balcony overlooking St Peter's Square. So papal tailors Gammarelli prepare three sets of vestments - in small, medium and large sizes. These will include a white cassock, a white silk sash, a white zucchetto (skullcap), red leather shoes and a red velvet mozzetta or capelet with ermine trim - a style revived by Benedict XVI. The Pope dresses by himself, donning a gold-corded pectoral cross and a red embroidered stole. (Popes traditionally wore red, but in 1566 St Pius V, a Dominican, decided to continue wearing his white robes. Only the Pope's red mozzetta, capelet and shoes remain from the pre-1566 days.)

8. Huge bets are laid. Experts suggest more than £10m ($15m) will be wagered as people guess which cardinal will get the nod - making this the world's most bet-upon non-sporting event. It's not a new phenomenon. In 1503 betting on the pope was already referred to as "an old practice". Pope Gregory XIV was so cheesed off that in 1591 he threatened punters with excommunication, but the gambling continues unabated. Prominent Italian and Latin American names currently lead the field.

9. Just say yes. Technically, an elected Pope can refuse to take up the position, but it's not really done to turn down the Holy Spirit. That said, few relish the prospect of leading the world's largest Church, beset as it is at the moment with falling congregation numbers, sex abuse scandals and internal wrangling. So many new popes are overcome with emotion after their election that the first room they enter, to dress for the balcony scene, is commonly known as the Room of Tears.

10. There is no gender test. Chairs with a large hole cut in the seat are sometimes thought to have been used to check the sex of a new Pope. The story goes that the aim of the checks was to prevent a repeat of the scandal of "Pope Joan", a legendary female cardinal supposedly elected pope in the 14th Century. Most historians agree that the Joan story is nonsense. Examples of the chairs, the sedes stercoraria, are apparently held in museums, but their purpose is unclear. One unconfirmed theory, external is that they were used to check that the new pope had not been castrated.

Reporting by Michael Hirst.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external