Frank McClean: Forgotten pioneer of the sky

- Published

Egypt these days is more intent on eradicating symbols of the past than honouring them. So there is little prospect of a largely forgotten Irishman Francis (Frank) McClean ever being hailed there for his extraordinary feat a century ago that heralded Egypt's golden age of aviation.

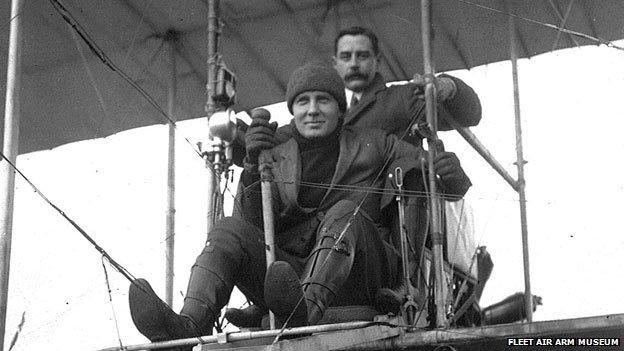

McClean, born in England to well-to-do Irish parents in 1876, was a pioneer aviator and something of a daredevil. Through a combination of unstoppable enthusiasm and access to ample funds, he became a driving force in the development of flying, having met and flown with one of the Wright brothers in France in 1908.

Eager to take to the air himself as often as possible, he also gave financial help to three brothers Oswald, Eustace and Horace Short - founders of one of the earliest aircraft manufacturing companies - buying and testing several of their planes. In 1911 he allowed the Admiralty to use land he owned in Kent to be used for naval flying - the first facility of its kind in the world.

The following year, Frank McClean made headlines and became a celebrity overnight when he flew a flimsy seaplane built by the Short brothers between the towers of Tower Bridge in London.

As if to dismiss that as too simple a challenge, according to press reports of the day, he then flew under at least three other, much lower, bridges - London Bridge, Blackfriars and Waterloo - before stepping ashore at Westminster to be greeted by a cheering crowd who had gathered to meet a dignitary expected by boat from Paris.

If seaplanes could land on the Thames, McClean reasoned, then why not on the Nile and other rivers in Africa? The enthusiastic aviator spent much of 1913 preparing for an Egyptian adventure.

Before the end of the year, the SS Corsican Prince docked at Alexandria. Large crates containing the parts of a Short seaplane were transported to a shed on one of the wharfs.

Once the biplane had been reassembled, it was put into the water and McClean took off, flying eastward to the Nile Delta, before turning south for Cairo and landing on the Nile. His eventual aim - to reach Khartoum.

Accompanying him on his venture was a co-pilot, Alec Ogilvie, and a four-man support team. Frank's sister, Anna, also tagged along. The aircraft could seat four people and the combination of those on board varied, with the rest of the team travelling overland. A passenger for part of the journey was Horace Short.

McClean's progress was smooth until he reached Aswan where, Short later recalled, "he made some flights to the delight of the great crowd which had gathered to see the machine." But after flying another 130 miles southwards he experienced engine trouble that resulted in a frustrating one month's wait for new cylinders to arrive from Europe.

Short returned to England before McClean had completed his mission. Back home, he was keen to tell of their adventures. He described the Egyptians along the Nile as having been terrified by the sight of the biplane, citing the case of two native carpenters who were required to do some repairs "refusing to enter the machine (although the engine was out) lest it should fly away with them".

But such fears don't appear to have been shared by the crowds of bemused and curious fellahin (peasants) who waded out towards the biplane whenever it landed on the Nile.

During McClean's flight to Khartoum and back (which took exactly three months), his aircraft's Gnome engine suffered no fewer than 13 breakdowns.

Cairo soon became a major aviation hub

In a letter written to Horace Short during one of the delays, the normally patient aviator expressed his exasperation at the technical problems he was encountering, adding that he was "getting tired of this series of happenings".

Slow and frustrating though the flight to Khartoum was, it proved that Africa could be penetrated by aircraft - and that it could be done without the difficulty and expense of finding suitable land and preparing airstrips.

When World War I ended, British Air Ministry teams took up McClean's idea and began stringing together a chain of seaplane landing spots that eventually linked Egypt with South Africa.

In 1925, the famous British pioneering aviator Sir Alan Cobham took off from Rochester in a plane fitted with floats on a route survey to Cape Town. His 26 stops included several on the Nile where McClean had landed.

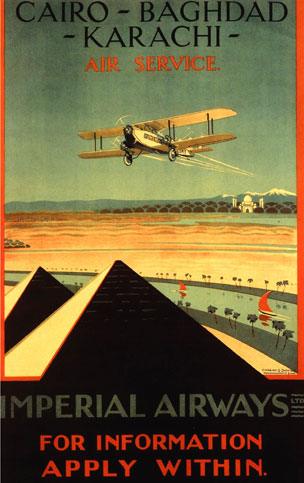

But it was not until 1931 that Imperial Airways introduced a weekly England-to-Central Africa service, terminating at Mwanza on Lake Victoria - with the route extending to South Africa at the end of that year.

Egypt by this time had established itself as a key stopover on several routes that were opening up to distant corners of the British Empire, with the giant four-engine biplane, the HP42 (the makers, Handley Page, called it the "first real airliner in the world"), taking passengers eastwards and southwards in luxury that has never been matched.

Mail destined for Cape Town is loaded on an HP42 at Croydon, December 1931

Cairo became synonymous with all the glamour and luxury attached to the early years of commercial flight.

As early as 1919, the head of civil aviation in Britain, Sir Frederick Sykes, had correctly predicted that "Egypt is likely to become one of the most important flying centres. It is on the direct route to India, to Australia, to New Zealand, while the most practicable route to the Cape and Central Africa is via Egypt."

A journalist the following year described Heliopolis as "the Clapham Junction of the Empire air routes".

Senior colonial civil servants would rest overnight in the grandeur of Shepheard's Hotel by the Nile in Cairo, before flying on as the 1930s progressed in newer and faster seaplanes southwards to postings in distant corners of Africa.

Two flying boats are prepared for a flight to Alexandria, in March 1937

For some, the stopover provided the opportunity to visit the city's infamous houses of ill repute.

But the luxury didn't end at Shepheard's. The following morning, a launch would ferry passengers to the waiting Imperial Airways Empire flying boat - a classic icon of the 1930s - and they would be regally wined and dined as the majestic airliner headed south.

By means of staging posts on rivers and lakes, the flying boat would lumber on sedately to Durban, which by the end of the decade had become its final destination.

Air passengers in the 1930s expected high standards of luxury

Egypt's golden age continued until World War II, after which Beirut took over the role as the region's flying hub. By this time, Frank McClean, the brave and determined Irishman who had done so much to show Egypt's potential as a centre of global aviation, had long been forgotten.

McClean flew with the Royal Naval Air Service during WWI and with the RAF for a short time thereafter. But he played no further part in the development of aviation in Britain, dying after a long illness in 1955 at the age of 79.

A statue of Frank McClean in Cairo is too much to ask of a country that has experienced two revolutions over the past 60 years. But this intrepid aviator who helped put Egypt on the aviation map a century ago surely deserves more than just a footnote in the country's history.

Gerald Butt is author of History in the Arab Skies: Aviation's Impact on the Middle East

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external