How to get along for 500 days alone together

- Published

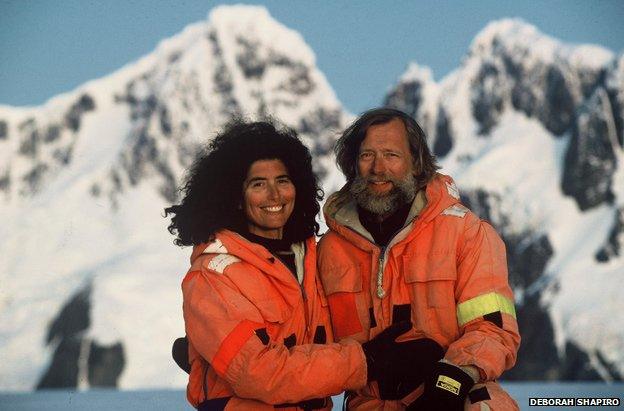

The search is on for a couple to train as astronauts, for a privately funded mission to Mars. But wouldn't any couple squabble if cooped up together for 18 months? Explorer Deborah Shapiro, who spent more than a year with her husband in the Antarctic, provides some marital survival tips.

It never ceases to amaze us, but the most common question Rolf and I got after our winter-over, when we spent 15 months on the Antarctic Peninsula, nine of which were in total solitude, was: Why didn't you two kill each other?

We found the question odd and even comical at first, because the thought of killing each other had never crossed our minds.

We'd answer glibly that because we relied on each other for survival, murder would be counter-productive.

Still, people do get cabin fever - an emotional disturbance that can affect people living in small spaces, in an isolated place.

Cabin fever usually manifests itself first in signs of irritation, and ends in violence.

At a remote Antarctic station during a winter, one man killed another over a chess game. The episode could have started from him not liking the way his colleague buttered his toast...

People can and do have a difficult time living together in this era of self-reliant independence.

We figure that a couple who ran a farm a few generations ago would be very likely to have a successful trip to Mars.

Why? Because a couple on a farm lived in interdependence, with accepted roles. They lived frugally, entertaining themselves, producing what they needed and repairing their tools that broke. All those traits are necessary for a long space voyage.

In hindsight, we can say that there are some guidelines for living in harmony in a confined space, and all of them fall into the category I call "simple, but not necessarily easy".

One has to be able to give the other person mental elbow room. During our winter, when a person settled into the sofa in the salon with a book and started reading, he or she was not interrupted.

Keeping quiet when the person is close enough to practically read one's thoughts, is a matter of self-discipline, fuelled by caring.

The only exception to our silence rule was for boat-related safety issues. The boat, for obvious reasons of survival, always came first.

Showing tangible signs of caring and of empathy ensures that cabin fever never takes hold. It's one of the personality traits Sir Ernest Shackleton looked for, when signing-on crew for his expeditions.

As Rolf, who has Shackleton as a role model, always says: "I can teach anyone how to sail, but I can never change a person's personality."

Two simple examples of our interaction - firstly, remaining sensitive to each other's moods and concerns, never belittling.

We learned early on that I, the novice, when scared, expressed anger. After it happened a few times, Rolf brought it to my attention.

"Whenever you are about to get in the dinghy to take photos of the boat sailing, your mood changes," he said. "You become aggressive and have lots of 'reasons' why we can't do it. Remember, you once agreed to take these photos."

My unspoken response was: Yeah, but that was before I realised the dangers. Then I had a think, and decided that I could not let my weakness jeopardise our documentary project.

Whenever I felt the anger, I would simply keep my mouth shut. As I gained experience, fear dwindled and the trait evaporated.

The second important rule, is that showing care benefits both.

We believe this to the point that it is built into our daily routine - we alternate cooking days. Each day's food becomes a present to our partner. We try to surprise the other with new dishes. There's a prize to be won - the other person's admiration.

Lives lived at close quarters

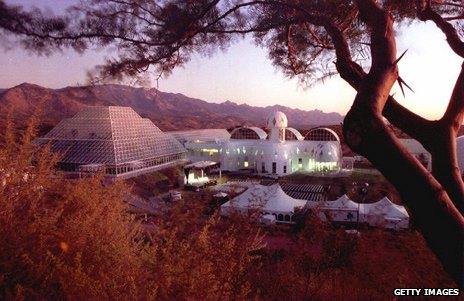

The Biosphere 2 research facility in Arizona, where eight inhabitants sealed themselves away for a two-year ecological research experiment in 1991.

They emerged back into the Earth's atmosphere in September 1993. Crew member Jane Poynter plans to join Inspiration Mars Foundation's mission.

Submariners may spend months at a time at sea, with the same faces in the same confined spaces - and with no windows.

Round-the-world yacht races add a competitive element to the pressure of living at close quarters in difficult conditions.

As well as isolation, those posted to research bases in Antarctica have to contend with freezing temperatures and sunless days over winter.

Temperament is an important consideration when choosing astronauts to live and work together high above the Earth...

... and in close-knit military units that will be posted abroad for months at a time, often in uncertain circumstances.

Lighthouse keepers and oil rig workers are also often separated from friends and family for months at a time.

But nuns and monks have traditionally chosen to withdraw into cloistered communities, emerging into the bustle of daily life to tend to others.

But sometimes - as in the Big Brother house - the personality mix may have been chosen in the hopes of sparking fireworks.

People sometimes joke that long-distance sailors must have a high boredom threshold, but my response is that one can only be as bored as one is boring.

Doing things is the antidote. We always have a creative project in progress - the documentation of the voyage itself.

There are hours of repairs to accomplish every day, just to keep things operational. In the evenings, we often play games. Or we read aloud for each other, pausing to discuss our reactions and thoughts.

We also developed thoughts during the winter as a team, mostly along the lines of our favoured subject: world politics and management.

Rolf came up with an idea he called Global Justice, a method of sharing non-renewable resource that doesn't generate war. It was based on an idea that whatever man has not created, he can't own. All winter we discussed and honed the idea.

It seems everyone who temporarily removes themselves from civilisation has these discussions.

Astronauts, who look back through the deadly distance to that beautiful planet they call home, have the supreme position. Their perspective is indeed unique.

In essence, our opinion is that a likely pair for the trip to Mars would be a loving couple who have been living together a long time, who are technically clever and bright, remain ice-cold under pressure, and are naturally upbeat - and whose main goal is to support each other through every phase of life.

Both Rolf and I still consider the 270 days we spent alone in Antarctica as the highlight of our lives.

Had our engine not broken down, we would have stayed for another year.

But there is a big difference between our small-scale expedition and a trip to Mars.

In a space capsule, the couple will have to depend upon a vessel they have not built, and the people working at space control.

The outcome of the project is therefore not just in the hands of the couple, and they must be willing to put their lives in someone else's hands.

That will demand a special strength.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external