What if you could mine the Moon?

- Published

Space exploration has long been about reaching far off destinations but now there's a race to exploit new frontiers by mining their minerals.

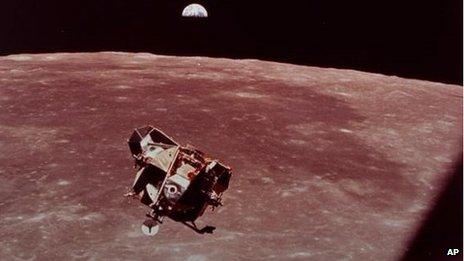

When Neil Armstrong first stepped on the Moon in 1969, it was part of a "flags and footprints" strategy to beat the Soviets, a triumph of imagination and innovation, not an attempt to extract precious metals.

No-one knew there was water on that dusty, celestial body. What a difference a generation makes.

Mysterious and beautiful, the Moon has been a source of awe and inspiration to mankind for millennia. Now it is the centre of a space race to mine rare minerals to fuel our future - smart phones, space-age solar panels and possibly even a future colony of Earthlings.

"We know that there's water on the Moon, which is a game-changer for the solar system. Water is rocket fuel. It also can support life and agriculture. So exploring the Moon commercially is a first step towards making the Moon part of our world, what humanity considers our world," says Bob Richards, CEO of Silicon Valley-based Moon Express, one of 25 companies racing to win the $30m in Google Lunar X Prizes.

It is considered to be among the top-three teams in the running for the prize. The other two are Pittsburgh-based Astrobiotic and Barcelona Moon Team.

Google's $20m first prize will be awarded to the first privately funded company to land a robot on the Moon that successfully explores the surface by moving at least 500m and sends high-definition video back to Earth.

A second place team stands to win $5m for completing the same mission, with bonus prizes for teams that travel more than 5km or find water. The deadline is 2015.

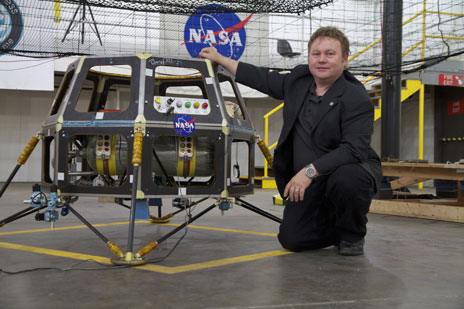

Bob Richards looks forward to the day the Moon hosts a colony of mining robots

But $30m is a relatively small amount of money when it comes to funding a Moon mission. The companies competing have business models far beyond the Google prize, with the real prize being the potential treasure trove of valuable minerals.

"The most important thing about the Moon is probably the stuff we haven't even discovered," says Mr Richards. "But what we do know is that there could be more platinum-group metals on the surface of the Moon than all of the reserves of Earth. The race is on."

But can anyone own the Moon, and what happens if multiple companies and countries succeed in getting there?

According to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty no nation can own the Moon, and most people believe that extends to individuals and companies. But would-be Moon miners can have something like property rights. And there is an advantage to getting there first and staking claims.

"Appropriation and ownership is not allowed under the treaty, but free access exploitation is encouraged," says space lawyer James Dunstan. "You can't own it, but you can go there and use it, so how do we balance those two?"

China has plans to land a probe on the Moon later this year and astronauts by 2020. Because China's lunar plans are more ambitious than most, some fear they may get too much control of the moon.

Dunstan does not think China would flout international laws to gain an upper hand in space, but it will be difficult to police.

"Trade sanctions would be very harsh if there were a rogue country or rogue corporation driving around ripping up other people's stuff."

If Moon Express and others are right, it's conceivable that in the future the lunar surface could host a colony of mining robots and astronauts who could use the Moon as a base to explore further into the solar system.

Alastair Leithead gets a look at the prototype Lunar Express lander

Richards believes humans will discover ways to live on the Moon permanently.

"We're becoming a multi-world species. That will happen. The first footprints on Mars by human beings will happen in our lifetime in the next 10 to 20 years," he says.

"People, themselves, will be transformed. They'll be merging with their technologies. And that which we call human will become redefined as we find how to reprogramme our bodies to live longer, how we find machines that are able to symbiotically work with us to cure disease.

"So that which we consider human today will continue to evolve."

Moon Express, which has its offices at Nasa Ames' research centre, is funded by entrepreneur Naveen Jain.

Jain says that location is key because he believes Silicon Valley will become the home to space pioneers.

"We are those crazy people who think that every idea is a crazy idea until we make it happen and then people say, 'Of course'," he says.

So, if we're going to live on the Moon one day, shouldn't we worry about polluting it? Won't armies of digging robots mess up our future real estate?

Nasa planetary scientist Margarita Marinova thinks we won't make the same mistakes in space that we've made on Earth and that man can't afford to explore space without tapping the local resources to survive.

"For me, it's a little hard because I do see these planets as very beautiful and very pristine in a way we don't really have on Earth anymore, and so the idea of mining is a little difficult," she says.

The potential resources from the Moon are vast. M Darby Dyar, a professor of astronomy at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, says the reservoirs of water ice in the dark, polar regions of the Moon probably come from comets that hit the moon over the past four billion years, and that future moon miners could strike it rich with precious metals in ancient lunar rocks.

But even if no company makes the 2015 deadline to win the Google Prize, Dyar says the Google Lunar prize has already yielded returns on Earth.

"I lived through the excitement of the Apollo era, my father helped design thrusters on the lunar landing modules and those remembered feelings of patriotism and wonder about the universe are what brought me into lunar science in the first place.

"When I hand a child a meteorite and tell her that it's four billion years old, her entire frame of reference changes, and that's what science should do. Not everyone wants to be a scientist but everyone can get excited about and learn to respect and understand its breakthroughs.

"Competitions like this bring science to the public's eyes. Where better than the Moon, which seems so close to us?"

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external