The story of how the tin can nearly wasn't

- Published

Tin cans have, in 200 years, changed the way the world eats. But Victorian disgust over a cheap meat scandal almost consigned the invention to rejection and failure.

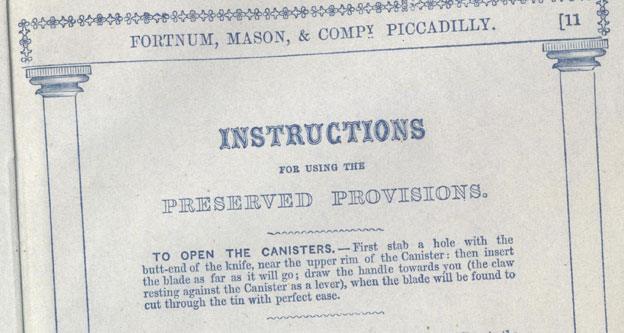

Bryan Donkin left the chimney smoke of the city behind as his carriage headed south through Bermondsey, with the Duke of Kent's letter of approval in his hand.

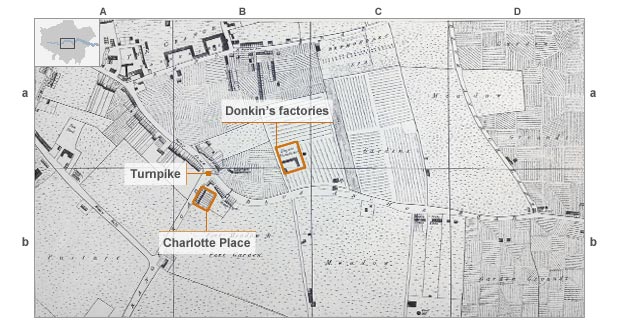

The smell of leather and hops receded as he came to the turnpike at Fort Place Gate, where the gatekeeper's two-storey, brick house marked the end of the urban sprawl.

Behind him was an unhindered view of St Paul's Cathedral while in front lay open land and his factory, where for the previous two years he had been trying to find the best ways to can food.

He could not have known that the impact from the contents of the papers he held would still be felt across the globe 200 years later.

Dated 30 June 1813, the day before, the letter explained that four distinguished members of the royal family - including Queen Charlotte, wife and consort of King George III - had tasted and enjoyed his canned beef.

Indulging such refined palates was not a matter of vanity for this modest Northumbrian engineer.

Instead, it meant he had the highest possible blessing to supply what are thought to be the world's first commercial cans of preserved food to the Admiralty, thereby sparing British seamen thousands of miles away the monotony of salted meat.

According to his diaries, held at Derbyshire Records Office in Matlock, the can-making operation had begun to mobilise on Monday 3 May.

A network of agents was based at key seaports to tout for custom from naval ships and merchants. The patent was finally his, the meat suppliers paid and adverts placed in newspapers, while business cards were engraved with the name of the company - Donkin, Hall and Gamble.

The factory occupied a rectangular plot of about 300 sq m, dwarfed by Donkin's larger plant for papermaking machines.

In the weeks that followed, within those four walls, sheets of tin plate were transformed by hand into tin cans filled with beef, mutton, carrots, parsnips and soup, destined for every corner of the British Empire.

And so the first faltering steps of a multi-billion-pound business were made. Today, households in Europe and the US alone get through 40 billion cans of food a year, according to the Can Manufacturers Institute in Washington DC.

But the road to success was almost derailed by a meat scandal in the 19th Century that - with echoes of today's horsemeat crisis - involved a Romanian meat factory and rocked public faith in canned foods.

Standing on the spot of Donkin's factory today, now a school car park on Southwark Park Road, there is little evidence of the industry which, 200 years ago, was about to spread around the globe.

Obscured by some scaffolding, a small white plaque says the first canned food was produced on this site. But it fights a losing battle for attention with the sign for Karma Supermarket's low-price beers, spirits and ciders - some sold in four-packs that could be described as the first cans' modern-day descendants.

Such a low-key commemoration reflects how mundane the tin can has become to us. Behind the door of a kitchen cupboard or lying discarded in the street, literally and metaphorically kicked down the road, it exists in the background of our lives.

It's a far cry from the days when its creation occupied the thoughts of some of the leading scientific thinkers in Britain and France.

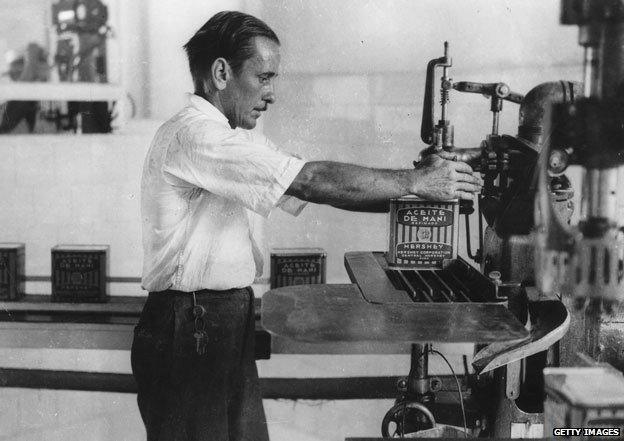

So committed were these bright minds to the technology of food preservation that they gave little thought to making a device to open their new invention, so for decades a hammer and chisel, a bayonet or a rock had to do the job.

The story of the tin can is one of ingenuity and endurance, and one that affects every one of us. It has changed the way we eat, the way we shop and the way we travel.

But its pioneers had no such lofty ambitions - they just wanted to fill the stomachs of sailors.

For all the military might available to the British, French and Dutch navies of the late 18th Century, the question of nourishment was on the minds of the warring admirals.

A solution to the conundrum of how to feed thousands of men while far away from a country's food supplies was one vital to national supremacy.

For 300 years, ordinary seamen had been eating salted meat and hardtack (biscuit), and malnutrition had killed more than half of all the British seamen serving in the Seven Years' War in the 1750s, says Sue Shephard, author of Pickled, Potted and Canned.

It meant, she says, the British and French were not only competing at sea and on land in the Napoleonic wars, but also vying to come up with a miracle food. In Paris, a financial incentive was offered.

The miracle maker took the unexpected form of a confectioner from Massy, south of Paris.

Nicolas Appert devised the method of heating food in sealed glass jars and bottles placed in boiling water. This was effectively sterilisation, decades before Louis Pasteur showed the world how heat killed bacteria.

Despite the impracticalities - glass was heavy, fragile and liable to explode under internal pressure - Appert has gone down in history as the "father of canning", despite not being the first to use tin plate.

He was awarded 12,000F by the French Ministry of the Interior - thought to be at the personal behest of Napoleon Bonaparte - on condition that he made his discovery public and in 1810 he duly published his findings in The Art of Preserving Animal and Vegetable Substances.

The French public and press were loud in their praises - "Appert has found a way to fix the seasons" said one paper. The French Navy used his method, but it was in England that Appert's idea was fully exploited and improved.

Within months, British merchant Peter Durand was granted a patent by King George III to preserve food using tinplated cans.

Tin was already used as a non-corrosive coating on steel and iron, especially for household utensils, but Durand's patent is the first documented evidence of food being heated and sterilised within a sealed tin container.

His method was to place the food in the container, seal it, place in cold water and gradually bring to the boil, open the lid slightly and then seal it again.

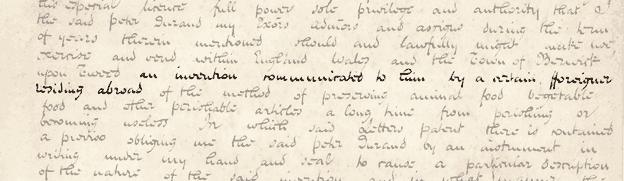

In some quarters, external, he is hailed as the "inventor" of the tin can, but a closer look at the patent, held at the National Archives in London, reveals that it was "an invention communicated to him by a certain foreigner residing abroad".

Extensive research by Norman Cowell, a retired lecturer at the department of food science and technology at Reading University, reveals that another Frenchman hitherto uncredited by history, an inventor called Philippe de Girard, came to London and used Durand as an agent to patent his own idea.

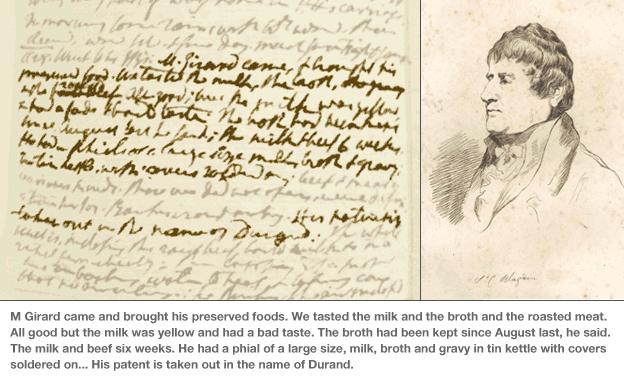

The smoking gun that unmasks Durand can be found in the almost illegible handwritten diary of Sir Charles Blagden, a fellow of the Royal Society.

Within these pages, in a big red book entitled CB/3/6 in the society's library, it is revealed that Girard had been making regular visits to the Royal Society to test his canned foods on its members.

And on 28 January 1811, Blagden explicitly says it is Durand's patent in name only.

Girard was forced to come to London because of French red tape, says Cowell, and he couldn't have taken out the patent in England at a time when the two countries were at war.

"The philosophy in England was entrepreneurial, there was venture capital. People were prepared to take a risk and go bankrupt. In France if someone had a good idea they took it to the Academie Francaise and if they thought it was a good idea they might get a 'pourboire' [tip]."

Durand sold the patent to engineer Bryan Donkin for £1,000 and he disappears from the story, having pocketed a fee and secured an elevated place in history.

Donkin, on the other hand, seemed to have a genuine interest in tin technology, and had already demonstrated a flair for making concepts work commercially.

He patented the first steel pen as an alternative to the quill and invented a device to measure the speed of machines.

Since 1802, at a factory site in Bermondsey, he had worked on turning an untested French design for a papermaking machine into a reality, a challenge that had already proved to be beyond other engineers. Within eight years, he had 18 so-called Fourdrinier machines in operation at mills around the country.

In 1811, his papermaking machine business turned in a profit of £2,212 much of which he invested in his new interest - canning.

He built a new factory on the same site in Bermondsey, where land was cheap but close to the River Thames docks. It was also near his home at the time, in Charlotte Place.

The enhanced functionality requires Javascript to be enable on your browser

1813

Now

The poor neighbourhood of Sabaa Qusour, where Marwa lives, has sprawled out since 2003.

It took Donkin two years to refine the method set out by Girard for use on a commercial scale.

The venture was partly funded by Sir John, who played little active part in the business. The other partner John Gamble led the experiments and the running of the factory when the cans rolled off the floor that summer of 1813.

The first high-profile plaudit had come from the Duke of Wellington, then Lord Wellesley, who wrote in April to say how tasty he had found Donkin's canned beef, and recommended it for both the Navy and Army.

Nine days after Wellington decisively beat the French at Vitoria in Spain, Donkin and Gamble presented their beef to the Duke of Kent at Kensington Palace on 30 June.

The duke requested more cans to try out on his family and the following day, Donkin collected the glowing letter from the Counting House in Lombard Street. The duke's secretary Jon Parker wrote:

"I am commanded by the Duke of Kent to acquaint you that his Royal Highness having procured introduction of some of your patent beef on the Duke of York's table, where it was tasted by the Queen, the Prince Regent and several distinguished personages and highly approved. He wishes you to furnish him with some of your printed papers in order that His Majesty and many other individuals may according to their wish expressed have an opportunity of further proving the merits of the things for general adoption."

Anything but fulsome praise from the royals might have spelt the end for Donkin's experiments. He had plenty of other projects on the go, according to his diaries, like a new counting instrument, a mill in Greenwich and a new shoemaking machine devised by Sir Marc Brunel.

His early cans ranged from four to 20lb in weight. The oldest survivor can be found in the Science Museum in London, measuring 14cm (5.5ins) high and 18cm (7ins) wide, and weighing a hefty seven pounds when filled with veal and taken by Sir William Parry to explore the Northwest Passage.

In 1813, the Admiralty bought 156lb of Donkin's food, feeding it to sick sailors, because it was mistakenly thought that scurvy was due to over-reliance on salted meat.

The praise from seamen for this unexpected addition to their daily menu was warm and glowing, from every corner of the globe.

William Warner, surgeon of the ship Ville de Paris, wrote in 1814 that canned food "forms a most excellent restorative to convalescents, and would often, on long voyages, save the lives of many men who run into consumption [tuberculosis] at sea for want of nourishment after acute diseases; my opinion, therefore, is that its adoption generally at sea would be a most desirable and laudable act".

In Chile, there is a cove named Caleta Donkin, so called because the crew led by Capt Fitzroy were so delighted with their canned food.

Donkin and Gamble even had a system of quality assurance - each can spent one month of incubation at 90-110C heat before going out.

And each was numbered to help track its origins. "This is the sort of thing that food factories today strive for," says Cowell.

Perhaps the most gratifying seal of approval came from Sir Joseph Banks, on behalf of the Royal Society, who opened a can of veal two-and-a-half years old and declared it to be in "a perfect state of preservation".

Banks went on to describe Donkin's work as "one of the most important discoveries of the age we live in".

On the back of such praise, business with the Admiralty took off.

In 1814, the order was for 2,939lb and in 1821 it was 9,000lb. Then other players came on to the market, clearly infringing the 14-year patent.

But Donkin's company was making money - prices ranged from 8d/lb for carrots to 30d for roast beef.

He expanded his client base by wooing polar explorers like Parry. For them, canned food was hugely beneficial because the perils of getting stuck in the ice all winter meant they had to haul two or three years of food on voyages.

Parry also brought with him preserved cocoa from Fortnum & Mason, purchased using his own personal account, as a treat for his officers and crew. The upmarket London retailer was quick off the mark to start a canning business on its Piccadilly premises, offering wealthy Britons - the Empire builders - a "taste of home".

Donkin's interest in canning ended in 1821 when he dissolved his partnership with Hall and Gamble. It isn't clear why, but the impression from his diaries is that canning was more of an engineering challenge than a passion.

Some of his personal letters reveal a man finding the commercial climate to be tough, as a debt-ridden nation adjusted to peace after years of fighting.

To his brother in 1817, he says: "What do you think will be the end of these portentous times? From the information I obtained during my recent peregrinations; universal distress seems to pervade the whole community of this country and the manufacturing part in particular."

These anxieties did not blunt his enthusiasm. Donkin continued his papermaking machine business and later assisted Sir Marc Brunel in tunnelling under the River Thames. He became a fellow of the Royal Society and a member of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Noting he had been a magistrate in Surrey in his later years, his obituary from the Royal Society said: "His life was one uninterrupted course of usefulness and good purpose."

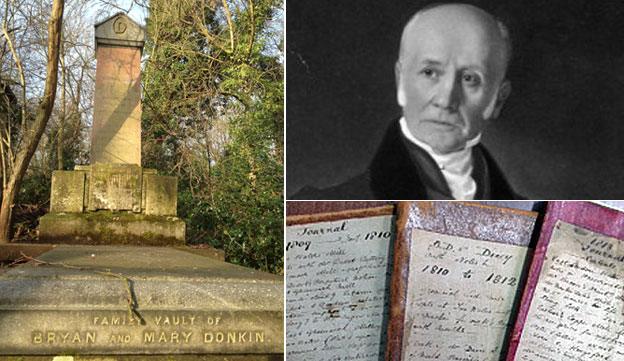

After his death in 1855, he was buried in a family plot in Nunhead Cemetery, south London. It's an indication of how much history has overlooked his achievements that on a recent visit, cemetery staff were unaware who he was.

His resting place is overshadowed by the imposing sarcophagus next to him for the shipbuilder John Allan. And even on his own grave, his name appears rather as a footnote, below three other relatives named Bryan Donkin and their spouses. There is no mention of his achievements.

Donkin was a fascinating man and a brilliant engineer who has been recognised in his sphere, says John Nutting, editorial director of The Can Maker magazine. But he's been forgotten by the wider world.

"That period from 1790 to 1880 was a blitz of all sorts of technical achievements and he wasn't in the forefront of what you would see from day to day. He wasn't a guy like Brunel who was involved in ships and trains and all those big infrastructure projects."

Donkin's engineering company remained in Bermondsey until 1902, when it moved to Chesterfield. His successor at the helm of the world's first tin canning business, John Gamble, moved the factory to Cork in Ireland in 1830, where there was a larger supply of cattle and the shipping route to the US offered an endless supply of custom.

When Gamble exhibited an array of canned foods at the Great Exhibition in 1851, to widespread approval, it must have seemed like the tin can's switch from military necessity to household must-have was only a matter of time.

But then came a food scandal that threatened to strike the fledgling industry with a fatal blow.

In January 1852, a group of meat inspectors gathered at the Royal Clarence Victualling Yard in Portsmouth and proceeded to open 306 cans of meat destined for the Navy.

It was not until they opened the 19th can that they found one fit for human consumption.

Instead of perfectly preserved beef, they found putrid meat so rotten that the stone floors needed to be coated with chloride of lime to mask the stench, according to an account in the Illustrated London News.

Sometimes the smell was so overpowering the inspectors had to stop and leave the room for fresh air before resuming their grim task.

They fished out pieces of heart, rotting tongues from a dog or sheep, offal, blood, a whole kidney "perfectly putrid", ligaments and tendons and a mass of pulp. Some organs appeared to be from diseased animals.

They condemned 264 cans that day, throwing them into the sea. The remaining 42 cans were given to the poor.

This scene was repeated across the country, as part of a nationwide inspection ordered by the Admiralty. They found meat at Navy depots to be "garbage and putridity in a horrible state".

A letter to the Times in 1853 revealed that officers of The Plover threw 1,570lb of canned meat overboard in the Bering Straits because "we found it in a pulpy, decayed and putrid state, and totally unfit for men's food".

The supplier in question was Stephan Goldner, who had won the Admiralty contract in 1845 by undercutting all rivals, thanks to cheap labour working at his meat factory in what is now Romania.

That contract grew significantly in 1847 when the Admiralty introduced preserved meat as a general ration one day a week. The following year complaints began to trickle in from victualling yards in the UK and from British seamen around the world that other parts of animals were being found in canned meat.

Despite this, Goldner was awarded another contract in 1850, with a warning that his meat needed to be genuine. In order to meet the demand, he asked if he could increase the size of the cans, but he didn't cook the meat sufficiently.

There are varying reports on how much of Goldner's meat was thrown away - one said more than 600,000lb to the value of £6,691

A government select committee was appointed to investigate and questions were asked in the Commons.

There was a danger that this bad publicity might put people off canned food for good, a threat that still lingered 10 years later.

Writing in Victorian London in 1865, the doctor and writer Andrew Wynter said: "It does seem suicidal folly on the part of the public to conceive a prejudice against a discovery which is of great public importance in a hygienic point of view, and which has been attested and proved."

Goldner was banned from ever supplying the Navy again. It was also revealed that he had supplied the meat to Sir John Franklin's ill-fated expedition that perished in the Arctic in mysterious circumstances in 1847.

Lady Franklin launched five ships in search of her husband, leaving Fortnum cans on the ice in the desperate hope that he would find them. In total more than 50 expeditions joined the search.

Bodies eventually recovered were found to have a high lead content and to this day, many people believe the 129 crew members were poisoned by leaking lead in their poorly soldered tin cans.

More recent research suggests the canned food supplied to Franklin was not acidic enough for that to happen and the lead was more likely to have come from the internal pipe system on the ships.

But the whole Goldner episode was a PR disaster for canned food, says author Sue Shephard.

"In Europe, Britain, Australia and America, people remained nervous of canned food and were reluctant to eat it. Now many also believed that it caused food poisoning."

Housewives wanted recognisable cuts of meat, she says, not flavourless, overcooked blocks of meat. Writer Anthony Trollope bought Australian canned meat for his servants and described it as "utterly tasteless".

A campaign got under way to promote the nutritional benefits of canned food, with advertisements appearing in the popular press and positive reviews from the Great Exhibition in London's Hyde Park.

These messages struck a chord at a time when the growing urban populations in Europe and the US were finding a voice through trade unions and co-operative societies, and demanding better food.

And the first canned food to penetrate the family budget came just in time to salvage the tin can's reputation.

"Condensed milk was the first mass produced object that people bought in shops, in the 1850s," says John Nutting, and it immediately changed the face of cities because urban farms gradually disappeared as people turned from fresh to canned milk.

By 1880, the UK was importing 16 million lb of canned meat, as industries sprang up around the globe, capitalising on the railways, roads and canals that were making the planet more connected than ever before.

In the US, Thomas Kensett and Ezra Daggett had patented the use of tin plate in 1825 and started selling canned oysters, fruits, meats and vegetables in New York. But it was the Civil War decades later that really kickstarted the industry, increasing output six-fold.

Mechanisation of can-making arrived in the 1860s and another major breakthrough came in 1896 with the arrival of "double seaming" which, according to Gordon Robertson, a food packaging consultant in Queensland, "made it possible to develop high-speed equipment for the making, filling and closing of these cans".

Brands like Bovril and Heinz capitalised on these and other technological developments that all led to a faster and more efficient means of canning.

The earliest Heinz baked beans can was 1895, then they came to London in 1901

Tinned food - including so-called bully beef - was introduced as an emergency Army ration in the Boer War, with Bovril the main supplier.

It became a mainstay of the British Army right up until the Falklands War in 1982, when the field rations consisted almost exclusively of tinned products, plus some sachets.

But three years later pouches, which were lighter and easier to pack, open and prepare, replaced cans.

The new emergency ration of canned beef alleviated the boredom of hardtack biscuits

Simon Naylor, a historical geographer at the University of Exeter, says the can enabled the British to tighten its grip on the Empire and it came to embody imperial strength.

The slogan "Empire Buying Begins At Home" became the hallmark of cans under a new national mark scheme introduced in 1930, he notes.

Canned food did help to maintain the empire, to an extent, says Philip Dodd of the National Army Museum, because it helped morale to have "British" food in the far-flung outposts.

But while the can was making strides, the can opener wasn't. And the Fortnum and Mason 1849 catalogue included instructions on how to cut tins with a knife.

The first tin opener was designed in the 1860s, but it didn't become a staple of household drawers until a second serrated wheel was added in 1925. By that time, the US was the biggest producer of canned food.

"Europe and Britain imported vast quantities of US Pacific canned salmon, and salmon canneries appeared at the mouth of almost every river as far north as Alaska," says Shephard.

In Iowa, there were vegetable canneries, in Chicago meat, while shrimp was canned in New Orleans, peas in Wisconsin and pineapples in Hawaii. Orange and grapefruit juice led a citrus boom in Florida.

The importance of canned food as a central part of the US food economy was further underlined when in 12 months in 1933-34, one of President Franklin D Roosevelt's New Deal Programs delivered 692 million pounds of food to needy people in 30 states, much of it canned beef.

American success was mirrored elsewhere on a smaller scale. South America and Australia had a ready supply of meat but before canning, there was no means to transport it overseas to market.

By the end of the 19th Century, some of the world's largest canneries could be found on the coasts of South America.

This boom among producers in the US and elsewhere meant that European households were experiencing some entirely new foods.

The first taste of corned beef was due to US imports to the UK, says food historian Liz Calvert Smith, where peaches and tropical fruits were also widely eaten for the first time. And tins gave many people who lived inland the first chance to taste sardines which, along with pilchards, were affordable.

A can-making machine in action at the Machinery Exhibition, in west London in 1902

The predominantly female workforce peeling ripe tomatoes at a US canning factory in 1930

In 1934, the Faversham Factory in Kent was one of the most up-to-date canning plants in the UK

The Women's Land Army canning fruit in Monmouthshire, soon after the start of WWII

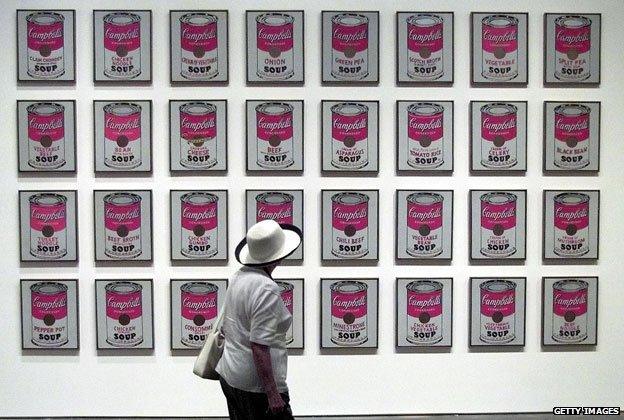

Canning peanut oil at Central Hershey, in pre-revolutionary Cuba, 1955

Canning meat for export in the Co-op factory near Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 1964

The tin can was an important part of the shift from agricultural to industrial revolution, says food blogger Sue Davies, allowing food to be harvested in season and eaten out of season. And agriculture had to respond to this.

After World War I, US food production increased dramatically through intensified planting and the introduction of fossil-fuelled traction power, chemical fertilisers and synthetic pesticides.

This was partly an attempt to meet the widespread civilian adoption of canned food, says Selcuk Balamir, a PhD fellow at the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis, but it put power in the hands of giant agricultural-industrial companies.

"Previously a military tool of European colonialism, the tin can would this time become the symbol of capitalism, serving the interests of the American Empire."

The grip on the imagination of consumers was perpetuated by advertising campaigns after World War II that presented canned food as aspirational and convenient.

In a 45-minute documentary entitled The Miracle of the Can, made by the American Canning Company in 1956, the narrator takes the audience through the technological advances of canning, punctuated by pictures of happy children being fed canned food by beaming housewives in sparkling 1950s kitchens.

"So the miracle of the can continues, bringing to countless supporting industries added expansion and prosperity, to millions of people more jobs, better security and a better way of life," says the narrator.

It was precisely because the tin can was everywhere, an unnoticed part of everyday modern life, that Warhol made prints of 32 soup cans in 1962.

The image became an emblem of the pop art movement.

Since this postwar heyday, the threats to the supremacy of the tin can have come in many forms.

Pet food is available in pouches, soups and drinks in cartons, while big brands like Heinz sell snackpots and fridgepacks.

New kitchen appliances - refrigerators and freezers in the 1960s, microwaves in the 80s - widened food choice and led to a proliferation of foodstuffs on supermarket shelves.

"The market is being constantly peppered so the number of cans sold has reduced, because the choices have become so much greater," says Nick Mullen of the Metal Packaging Manufacturers Association. But given this increased competition, sales of cans have held up well.

Mullen is optimistic about the can's future. "It's difficult to replace tins of fruit, tins of beans, tins of fish or soup. You can get soup out of a carton but it's very expensive and the difference in taste is marginal."

And the two big issues in packaging - food waste and recycling - work to its advantage, he believes.

There has been a shift in thinking from "packaging is bad" to "packaging prolongs life and reduces waste", he says, while at the same time the can is regarded as something that is easily recycled.

Tins have a unique quality, says packaging expert Gordon Robertson, so their ruggedness and impermeability will ensure that they remain an important part of food packaging for a long time.

The image problem bestowed on cans by the modern love affair with fresh food has not dealt it a fatal blow, although stores like Fortnums, once trailblazing in this grand experiment, now only stock tinned foie gras.

Canned and frozen food sales rose 11% in the US in 2009, according to Neilsen, which analysts explained by the habit of consumers to "cocoon" during times of recession, storing up on supplies.

Some countries remain impervious to canned food. In Vietnam, for example, food is mostly bought cheaply at market so nearly all the cans sold are for drinks.

But in Japan, the risk of earthquakes has people stockpiling cans of food, such as long-life biscuits. And the high price of fresh fruit adds to the appeal of canned fruit.

This global industry is powered by state-of-the-art technology. Factories like the Crown Bevcan plant in Leicester, UK, produce nine million cans a day, each one photographed to check there are no imperfections. The noise generated by the multi-tentacled robots that swing overhead at high speed is deafening.

Canning has come a long way since Donkin's fledgling factory opened for business in the summer of 1813, with a handful of people each making six cans an hour.

The Harris Academy school pupils who every day walk across the ground upon which this industry was born will soon be reminded of its significance. Head Dawn Rumley is planning a special assembly to mark the anniversary.

"It is exciting to think as we learn each day that this piece of world history existed right beneath our feet," she says. "And to see the tin can feature so prominently in our everyday lives 200 years later."

Whether the canned food industry is in such health come its 300th birthday in the year 2113 remains to be seen.

But the tins you have today in your cupboard will be.

Videos by John Galliver, audioslideshow by Paul Kerley

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external