Syria's priceless heritage under attack

- Published

Thousands have been killed and millions made homeless in Syria's civil war, but it has also caused irreparable damage to some of the world's most precious historical sites. The treasures now being destroyed matter to everyone on the planet, argues historian Dan Snow.

In August 2012 fire tore through the heart of the Syrian city of Aleppo. One Western journalist said parts of it, including much of the medieval covered market, or souk, were "burned to smithereens".

Old Aleppo is a Unesco World Heritage site, recognised by the world as being internationally significant, a vital piece of humanity's shared past. Central Aleppo was a stunningly preserved medieval settlement, probably the finest example of its kind in the world.

It was as if parts of Stonehenge or the heart of Edinburgh had been wiped out. The fire was caused by the vicious fighting that has swept across Syria since a civil war started in 2011.

More than 70,000 people have been killed, thousands more injured, imprisoned and tortured, and millions made homeless or turned into refugees.

I have just returned from Syria where I was making a programme on how Syria's history has shaped the current conflict. Many historic sites were too dangerous to get to. The Syrians I met, though, spoke grimly about the damage to the heritage of their country, aware that this is what makes Syria unique.

Syria is where it all began. Syria, and its surrounding area, was where humans first developed large scale farming, started living in complex cities and invented what is thought to be world's first alphabet.

Aleppo is one of the oldest continuously occupied cities on the planet. Geography placed Syria at the heart of human history. It sits astride the great artery of trade, the Silk Route, which links East with West.

Spices, fabrics, gold, ivory and other luxuries passed through the cities of Syria before either going east to Central Asia and China, or heading west, to the Mediterranean basin and beyond.

Conquerors followed the merchants. The ancient Egyptians, Persians, Alexander the Great, Romans, Islamic Caliphs, Mongols, Ottomans, French and British have sought to dominate this important region.

Syria has several Unesco World Heritage sites some of which, including Aleppo - pictured here in 2006 - have suffered immense damage

The city's citadel was built in the 13th Century, but this has not stopped it from coming under fire

Unesco has described Aleppo's Umayyad Mosque as "one of the most beautiful mosques in the Muslim world" yet its location means it has been caught in crossfire

Tourists flocked to Syria before the civil war to admire its rich heritage - they could contribute to the country's recovery if the fighting stops

Dan Snow visited several locations in Syria including the port of Tartus, which played a key role in the crusades

Each conqueror left their mark and Syria has some of the world's most precious historical sites. There are villages that sit on the cusp of pre-history and history, that show us how our species jumped from being hunter gathering to settled farmers, one of the most important shifts in our history.

There are Roman cities, the mightiest castles on earth, and the most beautiful medieval Islamic markets and palaces.

Now Syria's own people have turned on themselves in a vicious civil war. Civilian suffering has, quite rightly, dominated the headlines. However Syria's heritage is also under attack.

It feels cruel to talk of bricks and mortar while children freeze in unsanitary refugee camps, and yet these sites and treasures matter to everyone on the planet, and they matter particularly to Syrians, who will rely on them as the mainstay of their economy whenever peace is restored.

The heritage casualty list is deeply alarming. Syria has several Unesco World Heritage sites. Alongside Aleppo, are the old cities of Damascus and Bosra, the Crusader castles Crac des Chevaliers and Qal'at Salah El-Din, the Roman site of Palmyra and the Ancient Villages of Northern Syria.

Emma Cunliffe, Global Heritage Preservation Fellow and PhD researcher at Durham University, author of Damage to the Soul: Syria's Cultural Heritage in Conflict says all have been affected. Parts of Aleppo, she thinks, are irreparably damaged.

Alone, the loss of so much of Aleppo would be a tragedy, yet it is only part of a much larger picture. Mrs Cunliffe told me that she has 200 pages of notes on damage in Syria. There have been reports of looting in Bosra.

Crac des Chevaliers, one of the world's finest castles, has been shelled by artillery as the Syrian army attempts to dislodge rebel snipers. Refugees have re-inhabited buildings amongst the Ancient Villages, digging latrines, and scavenging for lucrative archaeological finds.

For thousands of years, empires and despots have fought for control of Syria

The Syrian government reports that there have been "illegal excavation acts in unexplored tombs in Palmyra". There are pictures that appear to show government tanks using the magnificent Roman colonnaded road.

For every World Heritage Site damaged there are countless less celebrated sites which are just as special.

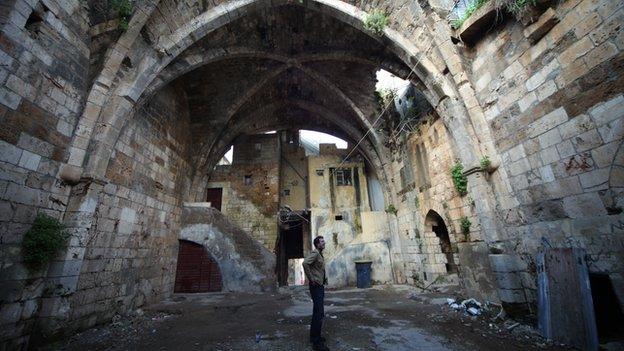

Lakhdar Brahimi, the UN Special Representative for Syria reported in September 2012 that important "mosques, churches and old markets" in the city of Homs now lie "in ruin". These include the Cathedral of Um al-Zennar which dates to the dawn of Christianity, 59AD.

After nearly 2,000 years of use, it's now silent and battered. Nearby there is a mosque almost as old as Islam. The Khalid ibn al-Walid Mosque, named after one of the greatest generals in history, known as The Drawn Sword of God, whose tomb it houses, has been shelled and badly damaged.

Mrs Cunliffe, and other experts I've talked to, have all said that the Syrian government's Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums is doing a heroic job, but the scale of the catastrophe is swamping its meagre resources.

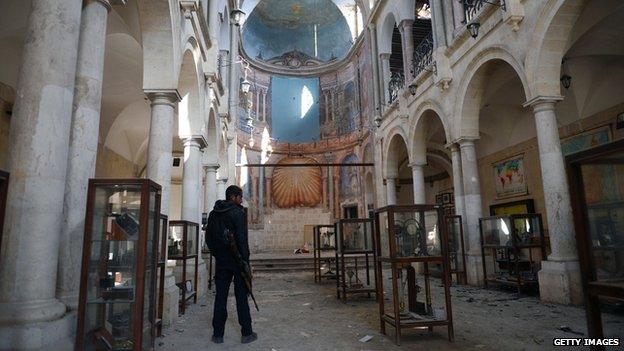

Artefacts have been removed from galleries, hidden in cellars and taken to secure locations but an organisation that lacked funds even in peacetime is struggling now.

The Syrian government has lost control of several stretches of its border. Treasures are being smuggled out and sold. One report claims $2bn (£1.25bn) worth of artefacts have already left the country.

Heritage binds communities together. Like the pictures, heirlooms and stories in a family home, it forms a bedrock of shared memory.

When the war ends Syria's treasures will be the foundations on which a shredded national identity can be rebuilt. Just as importantly, the tourists who were once drawn to Syria by the extraordinary heritage will return.

Tourism was vital to the Syrian economy and the only sector in which, before the war, massive growth was a realistic prospect.

If Syria's soul is to be healed, it needs its treasures, and if Syria's wrecked economy and impoverished people are to recover, its magical sites, and the tourists they attract, will play a central part.