Marwa's story: 10 years since the bomb fell

- Published

As the US military fought their way into Baghdad 10 years ago, the life of one Iraqi girl was changed forever when she was gravely injured in an air raid. Marwa's story, and charitable efforts by outsiders to rebuild her life, reflect the wider struggle of millions of Iraqis over the past decade.

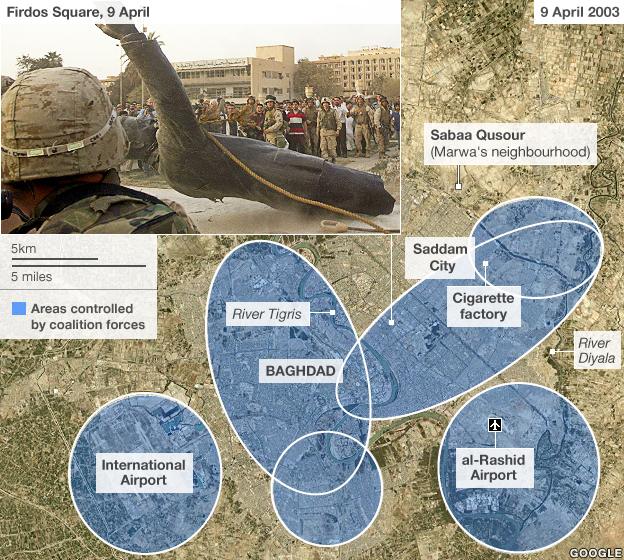

On 9 April 2003, at about the time that the statue of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad was coming down, Marwa Shimari was waking up.

The first thing that came into focus was her mother's face looking down on her in her hospital bed. She was trying to look reassuring, but you could see that she was frightened.

Marwa's brothers and sisters were there too. They were too young to understand what was really happening but she knew they were frightened too - their lively, mischievous big sister had been asleep for more than a day. They had been scared she was never going to wake up.

All of that seemed to register like a flash photograph in that split second between the last moment she was asleep and the first moment when she was really awake.

Then came the pain.

For someone who'd only ever felt the bumps and bruises of childhood there was something frightening about how much it hurt. It was like living in a world where there was nothing but pain.

Marwa can't remember when she first noticed that her right leg was missing - cut off far above the knee. The idea that her life had changed forever at the age of 12 was just too big for a child to understand.

"I thought my life was over," Marwa says.

There was no comfort in the memories of the last hours before the accident that made time stand still. She had been sheltering with her family in their simple home as an American air raid shook their village.

But "sheltering" is not the right word. The Shimari family home with its flimsy walls and roof offered only the pathetic illusion of shelter.

What they were doing was hiding from the American bombs - if you stayed indoors at least you couldn't see them, even if you could still feel the shaking of the earth trembling deep inside your own body and hear the shrapnel showering against the walls.

In an air raid it is the sound more than anything which robs you of your senses - it is so loud it fills the air around you and fills your head so there is no room to think.

As the bombs fell, Marwa decided to take her sister Adra and run from the house. When you ask her why, where she was running to, she shakes her head thoughtfully as though shaking off the memory of the noise, and confusion and terror.

She and Adra were just running to get away from the noise, chased by the sound of the explosions. She remembers running and running. And then there was one final explosion.

Adra, who was only eight years old, was dead.

And Marwa would never run anywhere ever again.

On the day that changed Marwa's life forever, the skies over Baghdad were cloudy. Somewhere above those clouds Capt Kim Campbell of the US Air Force was fighting for her life.

Campbell's troubles were out of step with the rapid progress American ground forces were making far below.

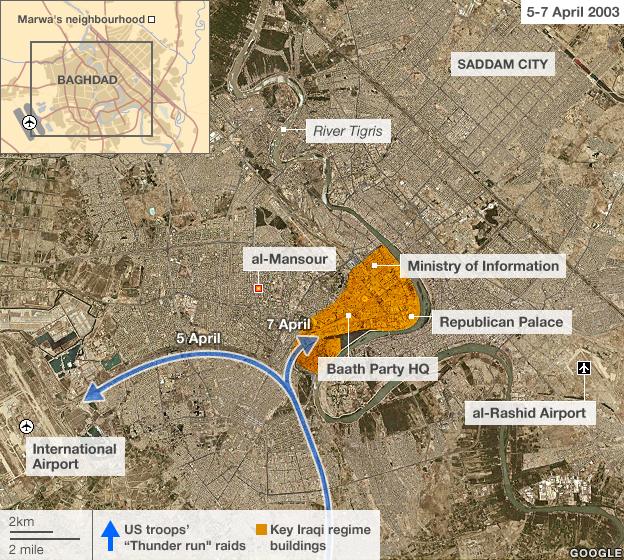

On a highway west of the city, the US commanders assembled a huge convoy of tanks and armoured vehicles, which they sent hurtling towards the city centre in a gesture that was both a show of force and a display of nerve. The US military loves tough, muscular-sounding jargon and they called it a Thunder Run. A Hollywood movie is in production.

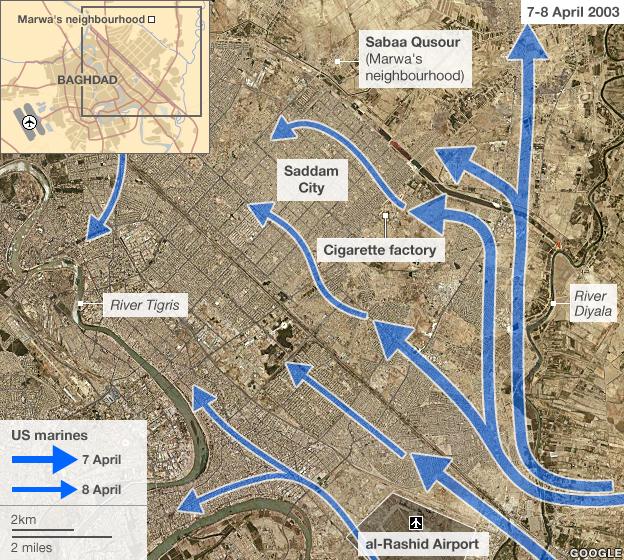

At the same time, the US Marine Corps was closing in on downtown Baghdad from the east, sweeping through Saddam City not far from where the bombs were falling around Marwa's home.

They sent their amphibious tanks across the Diyala River.

The scale of their resources and the level of their ingenuity disheartened Baghdad's Iraqi defenders. As one of them said later: "When we saw the tanks floating across the river we knew we couldn't win."

The battle for Baghdad

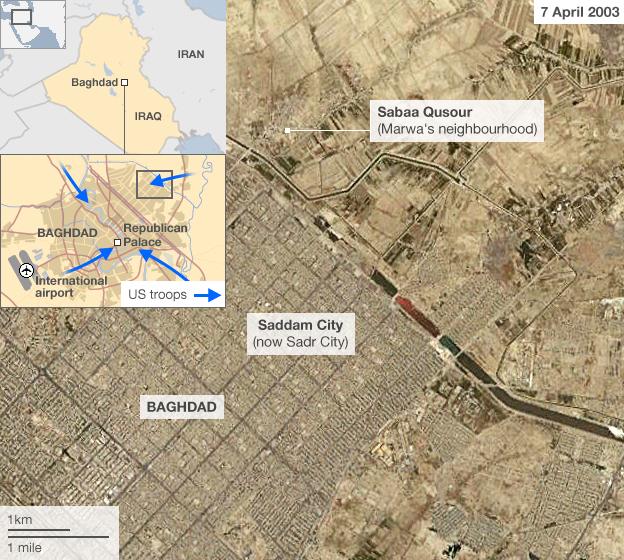

The war reached Marwa on 7 April 2003, days before Baghdad fell to the US-led coalition forces. US troops had taken the city's main airports, hit government buildings and were moving in from all sides. It is not clear what the target of the bomb that injured Marwa was, but ground and air assaults had been raging throughout the city.

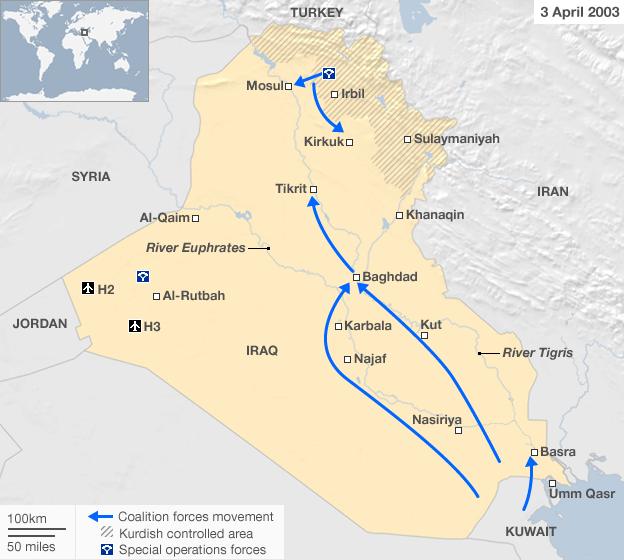

The invasion of Iraq had started three weeks earlier, with "shock and awe" air strikes on Baghdad and key targets, before ground troops moved north from Kuwait, through Karbala to the capital. Special forces conducted operations in the north and west of the country. On 3 April, US forces took Baghdad International Airport, but faced sporadic resistance.

With the airport secured, armoured units from the US Army's 3rd Infantry launched "thunder runs" through the city streets to test Iraqi defences. Having caught the Iraqis off guard, they did it again on 7 April, this time turning towards key government sites in central Baghdad. The US Air Force also bombed a "leadership" target in al-Mansour, killing a number of civilians.

As the army struck west Baghdad, US Marines attacked across the River Diyala to the east. They overwhelmed Iraqi forces armed with tanks, surface-to-surface missiles and artillery before seizing al-Rashid Airport. US forces set up base in a cigarette factory - dubbed Camp Marlboro - and the marines moved towards Saddam City and cordoned off any eastern escape routes.

On 9 April, US forces controlled much of Baghdad. The Marines rolled into Firdos Square and helped pull down a giant statue of Saddam Hussein. Iraqi troops put up resistance for a few more days in the president's hometown of Tikrit, but were soon overcome. On 1 May 2003, US President George W Bush declared the end of "major combat operations in Iraq". Saddam Hussein was not captured until December.

Campbell's fellow flyers had something of a taste for that muscular jargon too. They called her KC, short for Killer Chick. It was based on her initials (KC) but it's one of those handles that makes the military's dangerous and frightening business seem racy… a breeze, an adventure.

Campbell was flying an aircraft the air force calls the A10 Thunderbolt, but which is known to its pilots as the Warthog. She wasn't involved in the attacks around Marwa's home - her targets were elements of Saddam Hussein's Republican Guard, which were engaging an American armoured column in the heart of Baghdad.

The Warthogs are ungainly looking aircraft whose dangerous job it is to fly low and slow over battlefields, bringing their guns and rockets to bear on enemy targets below.

They fly in pairs - the more experienced of the two pilots operates as a leader with a wingman to watch his or her back.

Campbell, the wingman in her formation, can still remember sizing up the situation on the battlefield far below her.

"Initially it was shock - 'Wow they're really firing at us.' But the thing that stands out in my mind is that you recognise the situation the guys on the ground are in… and you do what you can, as quickly as you can, to help the guys on the ground."

Then she was hit.

"I would equate it to a car crash if someone was rear-ending you," Campbell says now, matter-of-factly. "I remember seeing Baghdad down below and thinking: 'Here's where we were just shooting at the Republican Guard. If I have to pull these ejection handles… and I land in the middle of them… this may not go so well for me.'"

Kim Campbell looks at her stricken Warthog (right), and a pair of A10 Thunderbolts in flight

There is a way of flying the Warthog using a network of cranks and cables after its sophisticated automatic systems have been shot away. It's called manual reversion and it's like driving a car without power steering, except it's a thousand times more dangerous.

Campbell nursed her A10 back to the safety of her base 300 miles (483km) south across the desert in Kuwait with a fellow pilot encouraging her with a carefully edited commentary on the state of her aircraft. He did tell her it was peppered with holes - he didn't tell her that small pieces of the engine were breaking off and spinning away in its slipstream.

Campbell was a young woman and she thought about the things she wanted to do in her personal life and the things she'd left unsaid. Then she got the plane down safely.

She was brave and resourceful but war is an arbitrary and fickle business - if the ground fire that hit her aircraft had been just a few feet to the right or the left then all that courage and resourcefulness might have counted for nothing.

The truth is that Kim Campbell was lucky. Marwa Shimari was not.

If you followed the allied invasion of Iraq on the television networks in 2003, then it would not have sounded like this, these stories of frightened little girls running in blind panic through the chaos of an air raid and lonely pilots grimly calculating the best way to stay alive.

Curving, sweeping arrows on brightly-coloured maps tracked the remorseless progress of the allied armies - the British pushing up towards Basra from the south and the Americans converging on the heart of Baghdad.

History has long since answered the questions that filled the news back then:

would those weapons of mass destruction be found?

would Saddam Hussein's forces really fight?

would the old dictator himself somehow hang on to power again?

But in times of war there are also tiny turns of circumstance that reshape lives forever. The piece of shrapnel that passes 1cm above or below an aircraft's control cables for example, instead of right through them.

Or the split second of hesitation before you decide to run for your life, which means you are right on the spot when a bomb explodes instead of safely past it.

Kim Campbell successfully landed her plane and served out a five-month tour of duty in Iraq before returning to other duties, with her war over.

Marwa Shimari's battles were just beginning.

No-one would argue that the village in which the Shimaris made their home had any strategic value.

It is a place of poverty, of guns and gangs. The crumbling pot-holed roads are really just tracks worn into the mud. The flimsy homes go up without government approval or building control. In Arabic it is called Sabaa Qusour, or Seven Palaces, but there's nothing palatial about it. If the city managers of Saddam Hussein's Iraq could be suspected of having a sense of humour, you might almost think the name was some kind of joke.

Not far from Sabaa Qusour there's a suburb of Baghdad called Sadr City (formerly Saddam City), a grim grid of shabby, crowded backstreets into which more than three million people are packed. It is dirty and chaotic. Electricity comes, when it comes at all, through a fragile-looking spider's web of bare wires that sags just above head height from post to pylon around the whole neighbourhood.

Many Iraqis speak of Sadr City as a place to be feared and avoided. It is said that is how the people of Sadr City in turn talk of Sabaa Qusour.

Marwa remembers a group of Iraqi army tanks arriving and seeking shelter from air attack by parking between their simple homes.

"The Iraqi soldiers didn't talk to us, they were frightened," she says. It wasn't even clear if the troops were heading out to the battlefield to confront the Americans or just running away from it.

As April went on, the US forces began to consolidate their grip on Sadr City. They occupied a disused cigarette factory, calling it Camp Marlboro, and began sending out patrols accompanied by Iraqi interpreters to demonstrate to the local people that things really had changed.

The mixture of military units that the Americans sent into battle was testament to the belief in Washington and London that modern Western armies can rebuild a society even as they're demolishing a regime.

Alongside the infantry units with their Bradley Fighting Vehicles and the tanks of the 2nd Armoured Cavalry Regiment there were soldiers from a Civil Affairs Battalion and a couple of Psyops (Psychological Operations) teams.

For a time the story of Iraq was the story of the American military's attempts to consolidate its grip on places like Sadr City.

How Sabaa Qusour has grown since 2003

The enhanced functionality requires Javascript to be enable on your browser

After the quake

Now

The poor neighbourhood of Sabaa Qusour, where Marwa lives, has sprawled out since 2003.

It is a shock to go there now and see how completely every trace of the American military presence has been eradicated. The danger from al-Qaeda-backed Sunni insurgent groups remains, but these days it's the job of Iraq's own security forces to deal with it.

In Sabaa Qusour, after that first devastating contact in 2003, the villagers saw relatively little of the Americans.

When patrols came, the villagers were scared and resentful.

"They were frightening," Marwa says, "angry, shouting, and pointing their weapons at us with grenades clipped to the front of their uniforms. They came into the houses looking for guns or pieces of cable - the kind of things you can make a bomb out of."

The soldiers didn't find anything in the Shimari house, but what sticks in Marwa's mind is the memory of her mother, running out of the house, terrified, when the Americans arrived. The first time you realise that your mother is scared is one of the most frightening moments of your childhood.

For Marwa this was the beginning of a year in which long, dark spells in bed at home were punctuated by periods in hospital.

She was depressed, and offers this bleak recollection of how life changed for a lively little girl who was a ringleader whenever there was mischief at school.

"Frankly at that age I didn't understand anything, only that I was hurting," she recalls. "I was crying with the pain and I couldn't think clearly about anything. I spent the daytime just crying."

There are no official figures for the civilian casualties of the war because the Americans and the British didn't collate them and the Iraqi authorities couldn't. But one estimate suggests that more than 2,200 Iraqis were killed in the week that Marwa was injured.

It is part of Iraq's tragedy that its oil wealth could easily have been spent on providing top-class hospitals as good as those of Switzerland or Germany or the US. But of course it wasn't. The ramshackle health system provided under the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein couldn't cope with the flow of casualties.

To get a feeling for what life was like in the hospitals of Baghdad at that point in Marwa's life, I went to an emergency room in the heart of Sadr City.

At first sight, if you're not used to life in Iraq, it seems daunting.

There's a young guard at the gate idly fiddling with a silver 9mm pistol, the buildings are a little shabby and the authorities seem to use only a special type of institutional light bulb that serves to intensify, rather than dispel, the gloom.

But that is only the skeletal structure of a hospital - the medical staff are its heartbeat and at the al-Sadr General Hospital the heartbeat is strong and steady.

A doctor tousles the hair of a tracksuited young man with acute appendicitis who is groaning plaintively as his friends push him along a corridor in a wheelchair.

"You're going to be fine," he says encouragingly.

Two young nurses in headscarves deal with a worried old man in long flowing robes who is demanding treatment at the reception desk. It's not clear what, if anything, is wrong with him but eventually the two young women take his blood pressure and he wanders off, apparently delighted with the reading.

The chief surgeon, Dr Wiaam Rashad al-Jawahiry, recalls the darker days of 2003 with a shudder.

"Don't make me remember those times," he says. "Things were desperate."

While we are talking about how many victims of bullet wounds and bomb explosions he has treated - "I wouldn't say thousands, but hundreds and hundreds," he says - a young man is brought in with a bullet wound to the chest.

The doctor is calm and methodical and manages somehow to direct his team, reassure the patient and carry on talking to me all at the same time.

The victim's father is brought in, breathless, his clothes spattered with mud. His mood hovers uncertainly between anger and despair. Patiently the doctor extracts the story of the incident.

His air of authority calms the young man's father but he still winces every time his son groans.

The injury was serious, but not fatal. Routine. Al-Jawahiry can remember when the toughest part of his job was standing in reception surrounded by the bodies of the dead and the dying, grimly calculating who was beyond help and who was not.

There weren't enough drugs or operating theatres and plenty of doctors left Iraq back in those days. But enough remained at their posts to keep the system going.

I tell Dr al-Jawahiry that he should be proud to have been a doctor in such a difficult place, at such a difficult time.

He shrugs modestly, but I feel proud just to have met him.

The healthcare system on which Marwa found herself depending was over-stretched and under-resourced.

The sorts of care that amputees need - physiotherapy and counselling as well as the fitting of the best possible prosthetic limbs - are precisely the sorts of care that systems like Iraq's struggle to deliver.

Marwa felt her life spiralling downwards into darkness.

Her father had died two years before the American invasion, and her mother's diabetes, which was eventually to kill her, was already showing signs of getting worse.

The little girl who had dreamed of being a doctor never went back to school.

Like many Iraqi children, Marwa was traumatised.

With her mother's health deteriorating, and her brothers and sisters still too young to really understand what was happening to her, she felt utterly alone. There was no-one to talk to and even if there had been there were no words to express her growing sense of desperation.

"I'm not the type of person who speaks out," Marwa says. "I keep my sadness and pain inside myself. I don't say it out loud."

It is hard to imagine a darker or lonelier time in the life of a child.

And then suddenly, out of the blue, help was at hand.

The Iraq war had always been controversial in Europe - even in Britain which was part of the coalition that sent troops to fight. That political scepticism - and a profound sense of shock at the devastation that modern warfare brings - quickly translated into an impulse to do something to help the people of Iraq.

To some Iraqis it was a little bewildering. It felt like the same people who'd sent aircraft to drop bombs were soon sending planes loaded with humanitarian supplies to help the victims.

But the help was desperately needed.

Everything was in short supply in Iraq, from the most basic hospital stores to sophisticated drugs for fighting cancer. There was a shortage of children's wheelchairs.

It was clear that many of the more seriously ill and injured couldn't be treated in Iraq, even if more supplies could somehow be flown in.

So charities began to look at ways of paying for children who'd been badly hurt to travel to Europe or America for treatment. It was expensive but the devastation in Iraq after the long years of suffering under the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein had done something to prick the world's conscience.

A great deal would depend of course on finding wealthy and generous benefactors prepared to take an interest in the children and their families.

And for once, fortune was about to smile on Marwa Shimari.

Like many Europeans, Jurgen Todenhofer was bitterly opposed to the war in Iraq. Unlike most of them, he decided to do something about it.

He made six or seven trips to Iraq in the years after the allied invasion and eventually wrote a book about the tragedy of it all.

He first heard about Marwa through the UN children's charity Unicef, and in the coming years they were to play important roles in each other's lives.

For Todenhofer, Marwa's story was a way of understanding the conflict.

"Marwa became for me a symbol of this war and of all wars because for those who started it the war is over now, but for Marwa it will never be over," he explains. "She will be living with her disability for another 30, 50 years. No-one knows how long."

Todenhofer wrote books about Iraq but wasn't content just to tell Marwa's story. He wanted to try to change the ending.

He had the contacts and the money to make a difference too. Before he began writing about the consequences of American foreign policy in countries like Iraq, he'd spent 18 years as a member of the German parliament.

His experiences in Baghdad read like a description in miniature of outside attempts to repair the damage of war in Iraq and to treat its casualties.

First and foremost, it is a story of extraordinary personal generosity.

In 2004 or 2005, Todenhofer paid for Marwa and her mother to travel to Germany.

A first operation cleared away the shrapnel still buried deep in Marwa's wounds to prepare for the fitting of a prosthetic leg. He paid for them to stay in a hotel while they waited and then when the leg was fitted he paid for their flight home.

But this was not merely an idle impulse of compassion from a wealthy man.

Todenhofer visited the Shimari family in their home in Sabaa Qusour to learn more about their lives. And the more he learned about those lives, the more he became determined to change them.

It wasn't easy. The people of Sabaa Qusour had always been suspicious of outsiders and now they had been traumatised by the US air raids too.

Todenhofer understood their anger but the truth of the matter was that Sabaa Qusour was a dangerous place in which to try to do good. And its people weren't inclined to see much of a difference between a German critic of the war and an American supporter.

"There was never any reason to bombard that part of the city," he explains. "Therefore they don't like Western people. The last time I was there I was told that if I come back I will not survive. I was threatened very, very aggressively. I must say I understand it. They don't like us any more."

The cleanliness and efficiency of German hospitals and hotels had come as a shock to Marwa. Then, when she finally came home, the chaos and hardship of her old life was harder to bear.

Todenhofer sensed her sadness and isolation. He was worried that she'd stopped going to school because people laughed at the way she walked on her prosthetic leg.

So he resolved to do more.

He bought the family a new home at a cost of about US $10,000 (£6,600) and then tried to set them up in a little business running a kiosk.

But shortly before her death, Marwa's mother sold their new house to raise the money to renovate the old one, then moved her family back in. Sabaa Qusour is a place of a deep, bred-in-the-bone conservatism which is resistant even to the most benign of changes.

And the idea of a young girl running her own business may feel like a sound solution to the modern European mind, but that's not how it would look to the old-fashioned Shia community of Sebaa Qusour. The kiosk idea never really got off the ground.

Ironically, given Jurgen's passionate hostility towards the allied military campaign, it's tempting to see in this a parallel for broader Western attempts at re-building in Iraq. The US is thought to have spent more than $50bn on reconstruction projects. It's not really clear what US taxpayers have to show for all that money.

Somehow donor generosity alone isn't enough.

Give money to the wrong people, or in the wrong way, or at the wrong time, and it will be like putting petrol in a diesel engine, or giving someone a transfusion of blood from the wrong blood group.

It will, in other words, as Western governments found, be difficult. But the difficulties didn't deter Todenhofer.

Marwa was a growing girl and in time needed a new prosthesis. Eventually, Todenhofer took her to the US for state-of-the-art medical care. It did not come cheap - the prosthetic leg alone cost $20,000. Privately, he thought the Americans should pay, they were responsible for Marwa's injuries after all. But they didn't. He paid again.

At the same time, Todenhofer was starting to wonder if there wasn't a downside to plucking a frightened and anxious girl from a shanty town on the edge of Baghdad and exposing her to life in the West in short bursts that were hard for her to make sense of.

"I am not really sure that it was a very good idea to bring her to Germany," he says now. "Because here she lived in a very good hotel. She saw the United States and met some very good people there. People called her the 'Little Princess' but then she had to go back to Baghdad and she wasn't a princess any more."

Marwa herself looks a little wistful when you ask her about those trips to Germany and to the US - everyone was very kind and very friendly, she remembers. Everywhere seemed very clean. She lapses into silence and you are reminded that she is a girl who keeps her painful memories hidden deep inside, and doesn't like to talk about them.

If Marwa's story were a work of fiction, it would probably end somewhere about here.

A kindly benefactor has emerged, wealthy, patient and generous, and while the overall story is one of sadness and loss, there is an uplifting and redemptive message about a stranger reaching across continents to aid a helpless child.

But real life is full of unanswered questions and unexpected turns. It rarely offers clear-cut lessons and messages. Things happen.

Todenhofer continues to provide Marwa's family with money to this day. His bitter criticism of the US invasion of Iraq and all that flowed from it would probably anger many Americans. But there's no doubt that he runs through Marwa's story like a bright thread through a dark tapestry.

The tapestry itself, though, remained unrelentingly dark.

Last year, Marwa's mother Fachla died.

The little girl whose life was filled with a sadness she never put into words, and who stopped going to school because the children laughed at the way she walked, was suddenly the head of the family.

When Marwa was 12, she wanted to be a doctor.

She wanted to help people of course, but somewhere at the back of her mind was the idea that being a doctor would mean financial security and respect.

Things that matter a lot when you grow up in Sabaa Qusour.

It wasn't an unrealistic ambition in Saddam Hussein's Iraq. It was a place that lived in the torturer's shadow, but it offered more opportunities to women than some other Arab societies. There were women doctors and public servants. In truth, being poor may have been more of a barrier to ambition than being a woman.

And unspoken in the background was the assumption that she would marry and have children one day. Probably one day soon. Iraqi Shias tend to marry young.

The injury - that split second in a single American air raid - changed everything, and her dreams of being a doctor died the day she decided she wasn't going back to school.

Her prospects of getting married were damaged by the nature of her injury. Marwa sees Sebaa Qusour as a place of solidarity, a place where "people look out for each other". But attitudes towards disability, perhaps especially in women, are not enlightened.

The matter is not discussed. Marwa is a young woman who values her privacy and dignity, but everyone knows it is one of the central facts of her life.

When her mother died from the effects of diabetes, aged 45, it fell to Marwa to take responsibility for two younger brothers and a sister who still live with her at home.

Things are not easy.

In a country which should be awash with the riches of oil, there are regular power cuts - one hour of current is followed by a two-hour blackout at the moment. And the water supply is cut off more often than not - two days on and three days off.

Marwa is matter of fact about it. "We buy barrels and jerry cans. We fill them in advance whenever we know the water will be off. We are used to it."

They are the practical concerns that worry any head of the house in Sabaa Qusour. And then, of course, there's the problem of getting teenagers to behave.

Marwa, who's only a couple of years older than the older brother, speaks with the exasperated affection which is the authentic tone of motherhood.

"You tell them to stop messing about and they just ignore you," she explains. "And they do it all over again. I remember my own childhood. My mum got fed up with me too."

Her youngest brother Sadaq, in particular, is proving a bit of a handful. Marwa rolls her eyes when she talks about him. But when I ask if he reminds her of what she was like when she was his age, she giggles. He does.

To try to understand a bit more about what it feels like to be 12 in one of Baghdad's more dangerous suburbs, we went to the Juhaina Elementary School which is buried away in a warren of backstreets in the heart of Sadr City.

A local police commander despatched a team of armed bodyguards to watch over us, but the girls were more interested in our cameras than in their guns. It's that kind of place.

The buildings are a little shabby and the school is running low on basic supplies. But Iraq isn't just short of books and whiteboards, it's short of school buildings too.

The girls share their bare classrooms with a boys' school in shifts. Today the boys were here in the morning and it's the girls' turn to come in the afternoon. Tomorrow they'll be back in the morning and the boys will come after lunch. One of the teachers says darkly that I can blame the boys for any signs of damage I might find about the place.

But Juhaina school has a kind of educational secret weapon in its principal Eman Abdulhussein, a tall woman in black robes who radiates a kindly authority.

The older girls packed into one overcrowded classroom fall into a respectful silence when she enters. Once she has them settled to their task, I notice her wandering off across the playground, gently holding the hand of a much younger girl who has somehow become detached from her own class.

The girls we have come to meet are 12, the age that Marwa was when she was injured.

Twelve feels like a good age to be in post-war Iraq, when childish dreams about the future are giving way to more concrete ambitions and thoughts of eventual marriage. Though it's not clear yet whether girls will have more opportunities, or fewer, in Iraq's post-war order, especially if the country becomes less secular.

I wanted to hear about the girls' hopes for the future, so they were set the homework of telling us what they wanted to be when they grew up, and why.

The girls are immaculately turned out and beautifully behaved. Some wear crisp, dazzlingly clean white headscarves. They queue patiently while we film and photograph them.

There is a young teacher in the making, a lawyer, two engineers and one girl who wants to be a journalist. She looks a bit taken aback to receive a discreet round of applause from our team when she has finished.

But the overwhelming majority of the girls proudly announce that they want to be doctors. It makes me think of Marwa.

The teachers are proud of the girls' performance and hopeful that some, at least, really will make it to medical school.

A great deal has happened to the girls' country in the course of their short lives - the fall of Saddam Hussein, the rise of a rather unstable democracy, and first the arrival, then the departure, of the allies.

And whichever one of those factors you choose to credit, the truth is that those girls have a better chance than Marwa ever had of seeing their dreams come true. They are 12 years old in a time of peace. Marwa was 12 in a time of war.

Ten years on from the invasion of Iraq, there is a huge temptation to try to judge whether the intervention was a success or a failure - a temptation to which we are certainly not immune.

And it is possible to make a couple of simple observations about how life is returning to the streets of Baghdad, where there are new restaurants and new car showrooms, and a new sense of normality in many places, much of the time.

But judging the outcome of military interventions like the allied invasion of 2003 will take many years. Certainly far more than 10.

Kevin Connolly at a British Commonwealth war cemetery in Baghdad, final resting place of soldiers who died in the Mesopotamian campaign of WWI

The frontiers of the modern Middle East were drawn when Britain and France carved up the assets of the defeated and collapsing Turkish Empire at the end of World War I. You could argue that we are still waiting to find out what the ultimate results of those self-interested manoeuvrings will be.

There's no guarantee, for example, that Syria, which was created as a nation at that point, will remain a viable unitary state when its current civil war is over. And if it disintegrates, what of Lebanon, another former French colony with close ties to its big, dangerous neighbour?

The same could be said of Iraq, where Britain tacked a Kurdish minority in the north on to the traditionally Arab land of Mesopotamia to create the modern state. It was the sort of shotgun marriage to which colonial administrators were dangerously addicted and it's possible that in the chaos of the modern Middle East, that Kurdish region is working quietly towards a kind of undeclared independence.

That process, which would spell the end of Iraq as we've known it, has taken nearly 100 years, which shows the danger of trying to make strategic and historical judgements after only a decade.

And even if history ultimately judges the allied invasion to have been a kind of catalyst that made Iraq a better place, that's not how it looked to Marwa. She remembers it only as a time of fear and destruction.

Her recollection of that time reminds you that war is only complex to strategists and historians. To its victims, it's pretty simple.

Marwa puts it like this. "We lived through a desperate time and we were afraid. We kept thinking at any moment that a bomb would fall from the sky and that we would die. We thought only about when the war would be over, nothing else. "

Jurgen Todenhofer, who poured so much of his time and money into trying to make a difference after the war, says on reflection: "There is no possibility to be successful after such a war. [Former UN Secretary General] Kofi Annan was right when he said everything is worse."

He reserves his harshest words for the political architects of the intervention, George W Bush and Tony Blair.

"They have a wonderful life now," he says. "Bush is a painter, he's writing a book and Blair is the peace envoy for the Middle East. And then you see Marwa. For her it will never be over. You cannot give a leg back to a little girl. She will never have a husband, she will never have a family of her own. That's a crime."

I said earlier that if this was a work of fiction, it would end at an uplifting moment, but that real life is less good at providing clear-cut moral lessons.

Well, it's equally true that real histories throw up twists of fate or aspects of a character that don't fit neatly into the main body of a story.

As I got to know Marwa, I noticed some of my questions made her smile.

When she told me her favourite film was Titanic and that her neighbourhood suffered at least one power cut every three hours, I calculated it would be possible for people to have watched the film without finishing it and realising that the ship sank at the end. That made her laugh out loud.

She even giggled when she watched a rather harrowing video I'd found of her receiving medical treatment shortly after she was injured. "My hair looks scary, ridiculous," she said.

When I asked her where she found the energy that lights up that smile after all she's been through, she said simply: "It's my family. Each of them gives me something to smile about."

Then, after a little pause, she smiled and said: "Your character doesn't change."

On the 10th anniversary of the allied invasion, you can expect plenty of efforts to define the meaning of the war in Iraq, plenty of debate over what lessons - if any - it has to teach us.

But in that simple testament to the durability of the human spirit lies perhaps the most important lesson of them all.

Video by Adam Campbell. Photographs by Hadi Mizban of AP. Additional research by Edwin Lane.