Home towns struggle with legacy of Stalin and Hitler

- Published

The birth towns of Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler are divided on the issue of how to deal with the legacy of the dictators who slaughtered millions.

In some ways it would be hard to imagine two more different places than Gori in Georgia and Braunau am Inn in Austria.

Gori, with its crumbling Soviet-era apartment blocks, is set in the foothills of the Caucasus mountains.

You can still see scars from the 2008 war between Georgia and Russia, when Russian troops entered the town.

It is poor. Even in winter, pensioners try to earn a few pennies, helping cars to park.

Braunau, by contrast, is a comfortable little Austrian town, with a beautifully preserved medieval centre.

Cross the bridge over the Inn river, close to the main square, and you find yourself in Germany, in Bavaria - one of the wealthiest parts of Europe.

Hitler spent the first three years of his life in this house in Braunau

But the towns have one thing in common - they have become known for their most notorious sons.

Adolf Hitler was born in Braunau in 1889. Joseph Stalin was born in Gori a decade earlier.

"Some people here will be very upset if you compare Stalin with Hitler," one Georgian told me.

"They see him as our local hero, the Georgian boy who won World War II and changed the world. But other people - especially the Westernisers - hate him, as a bloody dictator who suppressed Georgian independence."

"I am not trying to equate the two men," I replied. "I am just curious to see how each town deals with the legacy."

In Gori, the row over Stalin has changed the town's appearance.

For years, the main boulevard, Stalin Street, was dominated by a huge statue of Stalin.

But in 2010, it was taken down by the pro-Western government of Mikhail Saakashvili, much to the dismay of many in Gori.

"I used to ride my bicycle round it when I was a kid," Lella, who is 39, told me as she served me tea.

She showed me a photo of the statue taken in the 1950s, which she keeps on her mobile. "We need it back," she said. And her wish is about to come true - partly because of a political upheaval in Georgia.

Last year Saakashvili's party was defeated in parliamentary elections by the Georgian Dream coalition, which wants to repair Georgia's relations with Russia.

A few weeks ago, Gori city council, now run by Georgian Dream, allocated funds to re-erect the statue.

It will not be returned to Stalin Street, but will be put in Gori's main tourist attraction, the Stalin museum, which is still a shrine to the dictator and scarcely touched since it was built in 1957.

The statue of Stalin in Gori's main square was removed in 2010

In Braunau, having a Hitler Street would be unthinkable.

The 17th Century former inn where he was born, is unmarked. All that links it to Hitler is a stone on the pavement, which says, "Never again Fascism. In memory of millions of dead." Hitler's name does not appear.

"We thought about putting up a plaque on the house - just to mark the historical fact," a town official told me. "But the owner would not let us."

He lowered his voice. "She is difficult," he said. "And so is the subject of Hitler."

Braunau is torn between those who think Hitler should be more openly discussed, and those who just want the issue to go away.

"We are not guilty because Hitler was born here," one man told me. "We do not need to apologise for our town."

But Florian, a local historian, disagreed. "Even though Hitler only spent three years of his life here, Braunau is contaminated," he said. "We have to speak out against Nazism."

During the Third Reich, the Nazis bought the house from the owners, a family named Pommer. After the war, the Pommers bought it back.

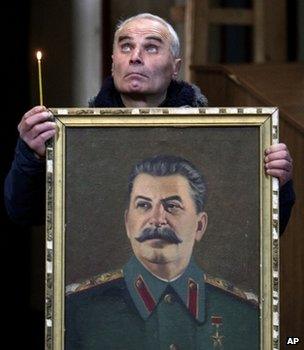

Some Georgians visited churches in Gori this week to mark the 60th anniversary of Stalin's death

Since the 1970s, the Austrian interior ministry has rented it from the current owner, Gerlinde Pommer, to prevent neo-Nazis using it as a shrine.

Until 2011, the house was used as a day-care centre for disabled people.

But they had to move out because Mrs Pommer did not agree to renovations. The simmering debate over how to deal with Hitler's legacy burst into a fully fledged row.

Some want the house to become a centre of responsibility, confronting the Nazi past. Others say it should be used for flats, or a college for adult education.

One far-right politician says it should become a clinic, where women can give birth. A Russian MP even offered to blow it up.

When I phoned Mrs Pommer's lawyer for comment, the secretary hung up on me.

In Braunau, Hitler is largely hidden, while in Gori, Stalin is very much on display. Opposing reactions to a difficult legacy.

When I asked one man in Braunau which was best, he shrugged. "You get criticised whatever you do," he said, "but it is usually better to talk."

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external