Woodrow Wilson's odd early press conferences

- Published

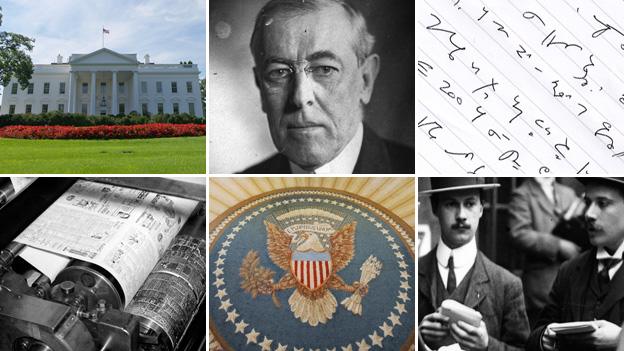

In March 1913, Woodrow Wilson began the first regular US presidential press conferences. By modern standards, they were a strange, awkward affair.

It was 12:45 on 15 March 1913 when a throng of more than 100 reporters trudged warily into the Oval Office.

There was a short silence before one of the journalists dared ask a question of the forbidding figure before them - newly elected President Woodrow Wilson.

According to Edward G Lowry, present on behalf of the New York Evening Post, Wilson replied "crisply, politely, and in the fewest possible words".

In his memoirs, Lowry recalled: "A pleasant time was not had by all."

The scene could not be further from the boisterous atmosphere of a modern-day White House media briefing, in which reporters demand answers to uncomfortable questions and dissect every utterance for gaffes.

By contrast, the mood at Wilson's question and answer sessions was deferential - and all quotes were strictly off the record.

But archaic as they now appear, Wilson's early press conferences set the tone for all that followed, and transformed political reporting forever.

No transcript exists of the very first session. But shorthand notes taken by the president's stenographer, Charles Lee Swem, record in detail the dialogue between the commander-in-chief and the press corps during those that followed.

"I want an opportunity to open part of my mind to you, so that you may know my point of view a little better than perhaps you have had an opportunity to know it so far," Wilson told the journalists on 22 March 1913, while apologising for the stiffness of his first performance.

A "large part of the success of public affairs depends upon the newspapermen", he added. "Unless you get the right setting to affairs - disperse the right impression - things go wrong."

Today, such a statement is axiomatic. But Wilson - who had edited the student newspaper at Princeton University and toyed with a career in journalism - was ahead of his time.

"At the time, journalism wasn't much of a profession," says David Ryfe, associate professor at Reynolds School of Journalism in the University of Nevada, Reno.

"Many were uneducated, many had second jobs because they were unable to make a living out of it."

In his previous job as governor of New Jersey, Wilson had pioneered the use of press conferences, and he was persuaded by his private secretary, Joseph Tumulty, to continue them in the White House.

While his predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt, made efforts to develop a good working relationship with journalists, he briefed them only irregularly.

The transcripts of Wilson's press conferences, show that he liked to remind the press pack who was in charge, giving terse, dismissive replies to what he considered unworthy questions.

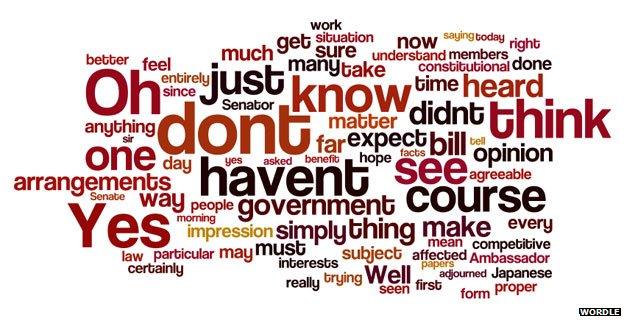

The most common words used by Woodrow Wilson in three early press conferences (April 1913)

Two of the president's most frequently recorded remarks are "No, I think not" and "Oh, no" - words that would curtail discussion of the subject, and signal the need for a new question.

The balance of power was demonstrated even more clearly in July 1913 when the conferences were temporarily suspended, after several newspapers printed controversial remarks by Wilson about Mexico.

"At that point, he could dictate the rules and the rules were that it was off the record," says Martha Joynt Kumar, professor of political science at Towson University and author of Managing the President's Message: The White House Communication Operation.

He could be witty, however. "I am not as big a fool as I look, and if you will just go on the assumption that I am not a fool, it would correct a good many news items," he remarked at one press conference in 1914.

On Washington's lobbying industry, a perennial fixture, he had this to say a year earlier: "This town is swarming with lobbies, so you can't throw bricks in any direction without hitting one, much inclined as you are to throw bricks."

Remarkably, he answered questions across the full range of government business off the cuff and without briefing notes, though he was known to prepare extensively.

Overall, the tone is of a wry senior academic tutoring an awed student seminar - perhaps unsurprisingly, given that Wilson had previously served as president of Princeton, and two of the press corps, Arthur Krock and David Lawrence, were his former students.

"He was a professor and his view of political leadership was that it was about educating the public," says John Milton Cooper, Wilson's biographer.

"He wanted to elevate the level of public debate. He wanted people to understand."

Wilson held 64 press conferences in 1913 and 64 more in 1914. In 1915, however, they became less frequent, and in July he cancelled them altogether.

The stated reason was the pressure of the tense international situation - a German U-boat's torpedoing of the RMS Lusitania in May of that year cost 139 American lives - but many reporters suspected Wilson had simply got tired of them.

Ryfe argues that there was a fundamental disconnect between what the president and the press wanted from the briefing sessions.

"He's trying to get them onside, to work with him and help the public understand the issues," Ryfe adds.

"But to them, they're talking to the president purely because he is news. They don't have any business helping him do his job. This was a tension from the very beginning."

Cooper, however, believes Wilson was genuinely concerned about inadvertently spreading misinformation after the sinking of the Lusitania.

The president resumed the press conferences after his re-election in 1916, although they were conducted less frequently than before.

"I don't buy the notion that he was submitting himself to something he didn't like," Cooper says.

"I think he enjoyed it well enough. Wilson liked public speaking, He liked to campaign."

Wilson reformed the White House's communications strategy in other ways, too. He was the first president to deliver the State of the Union address to Congress in person since Thomas Jefferson discontinued the practice in 1801.

All of Wilson's successors felt compelled to hold press conferences, although the balance of power remained with the president into the second half of the 20th Century.

When in 1950 Harry Truman remarked that "the greatest asset that the Kremlin has is Senator McCarthy", reporters warned the quote would provoke an uproar and agreed to "soften" it.

The change in dynamics came with the arrival of television cameras during the presidency of Dwight Eisenhower, and of live screenings under John Kennedy.

"Since then they've changed from being low-risk to high-risk," says Kumar.

A modern president facing the media on the record now runs the risk of being caught out or held hostage to fortune by an ill-advised, inaccurate or ambiguous remark made in the heat of the moment.

While the Wilson style of conducting press conferences may appear primitive to 21st Century eyes, his innovation nonetheless transformed the media landscape irrevocably.

"It began the precedent that journalists had the right to routinely question the president," says Ryfe. "That's meant journalism became an institution."

As they traipsed warily into the White House, and as often as not had to accept No for an answer, that timid 1913 press corps nonetheless delivered a huge story.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external