Australia's coup culture

- Published

Julia Gillard and her predecessors: Kevin Rudd (main picture), Kim Beazley (top right) and Paul Keating (bottom right)

Australia has one of the most brutal political cultures in the democratic world, in which party leaders are dispatched with abandon. As yet another prime minister faces down a threat from her own side, has the country become the "coup capital" of the world?

Not yet three months old, 2013 is already shaping up as one of Australian politics' more casualty-strewn years.

The wounded and slain include the chief minister of the Northern Territory, who suffered the humiliation of learning that he had been deposed as leader by telephone, external while on a trade mission to Japan.

Elected last year, in a victory that brought 11 years of Australian Labor Party (ALP) rule to an end, Terry Mills had spent just over six months in the job.

The Premier of Victoria, Ted Baillieu, survived longer - just over two years - but decided earlier this month to resign as leader, external before being pushed as scandal engulfed his office.

Weeks earlier, the Liberal leader in South Australia, Isobel Redmond, who once famously volunteered to be tasered by police, also became the victim of a party room mutiny., external At the state and territory level, three party leaders have gone in as many months.

Canberra, the nation's capital, offers no refuge from the bloodletting. If anything, it is even more vicious.

Four Liberal Party leaders (clockwise from top left): Malcolm Turnbull, John Howard, Brendan Nelson and Tony Abbott

The Prime Minister Julia Gillard, who only last year survived a leadership challenge, was today forced to face down another "spill" as these party room votes are popularly known.

In 2010, she herself was the beneficiary of a coup, knifing her one-time boss, Kevin Rudd, less than 1000 days into his first term in office.

Four years earlier, Ms Gillard had also played the decisive role in helping Rudd oust his predecessor, the gaffe-prone Kim Beazley. In the past decade alone, the ALP has had five different national leaders.

On the conservative side of politics, the Liberal Party has seen an even higher attrition rate.

It has had four different leaders in the past six years - its once-dominant prime minister, John Howard, the short-lived Brendan Nelson, the hugely ambitious Malcolm Turnbull and the present incumbent, Tony Abbott.

Whether in government or opposition, party leaders have about as much job security as managers of Chelsea.

Canberra, then, is in danger of becoming the coup capital of the democratic world. Arguably, it is already.

Party leaders face off - but the real danger often comes from their own benches

Perhaps its stiffest challenge comes from Sydney, the state capital of New South Wales. Here, the Labor Party has seen five different leaders over the past eight years. Between 2008-09, it had three different premiers.

Small wonder commentators refer to the "New South Wales" disease, even though it now seems like a nationwide contagion.

For the watching world, this high political casualty rate must be somewhat perplexing. Australia, having weathered the last three global downturns, has enjoyed 22 consecutive years without recession. So why are its politicians, who have contributed to this national success story, nowhere near as resilient?

First of all, there is a ruthlessness that astounds even hardened political operatives from Westminster and Washington.

In its 113-year history, the British Labour party has never knifed a leader. The ALP is nowhere near as squeamish or sentimental.

At its most pitiless, it dumped the leader Bill Hayden on the eve of the 1983 election and installed in his place Bob Hawke, a freshman parliamentarian.

After eight years as prime minister, Hawke himself was "rolled," to use another Australianism (that politics here has its own vocabulary of leadership challenges is in itself instructive).

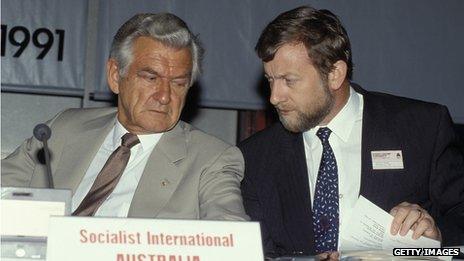

Bob Hawke (left): sacked after four consecutive election victories

A ministerial delegation tapped him on the shoulder and urged him to resign, with Gareth Evans, the then foreign affairs minister, delivering the now immortal line: "Pull out digger."

In came Paul Keating, who had mounted a leadership challenge six months earlier, and then gone to the backbenches to plot another takeover bid.

Charismatic and folksy, Hawke was Labor's best-loved prime minister, but the romance ended heartlessly.

Hawke had led Labor to a record four consecutive victories, but Keating was seen as the best bet for keeping the party in power. The fact that he went on to do so in the 1993 election validated the idea that you had to be cruel to be re-elected.

The influence of factional powerbrokers, the so-called "faceless men," also sets Australian politics apart. Whether from the "New South Wales right" or the "South Australian left," the leaders of these factional groupings wield enormous power, not least because if MPs defy them they risk de-selection as parliamentary candidates.

In Australian constituencies, MPs often have as much to fear from their fellow party members as they do from the electorate.

On the eve of the 2010 leadership contest, for example, it became obvious that Kevin Rudd was about to be felled when Paul Howes, the leader of the Australian Workers' Union, appeared in a late night interview on national television to announce his withdrawal of support.

A small handful of key powerbrokers have the ability to overthrow a prime minister, which is why leadership challenges can be mounted so speedily and, in Rudd's case, so stealthily. All it takes is for a few factional players to start pressing their speed dials.

A fixation with public opinion polling exacerbates the problem. Because of the attention lavished on them, Canberra makes a mockery of the political cliché that "there's only one poll that counts".

Indeed, weekly polls published by Fairfax newspapers (the Sydney Morning Herald and the Melbourne Age) and The Australian have become major news events in their own right.

And in a country not exactly awash with breaking news, they regularly dominate not just the front pages but also the radio and television bulletins.

When Rudd suffered from a string of mediocre polls early in 2010 (although his numbers, compared to Julia Gillard's, were actually not that bad) it led quickly to his downfall.

Rudd, who had once been considered a very promising leader, did not even get to contest another election.

The hothouse effect of Canberra, combined with the effect of Twitter's 140 character news cycles, means politics is almost always close to the boil. With relatively few other distractions, palace gossip and backroom intrigue are the highest form of entertainment.

Spills, coups and leadership speculation have become so embedded in the political culture as to become the rule as much as the exception.

As I wrote this piece, numbers were being counted, factional players were being sounded out, and a leadership challenge was in the offing. But it turned out to be a contest without a challenger, and a spill without bloodshed, with Julia Gillard re-elected as leader of the Labor Party unopposed because Kevin Rudd did not have the numbers to oust her.

With the prime minister this morning delivering a moving apology to victims of the policy of forced separation, this should have been one of the more solemn and orderly days in the parliamentary calendar. An occasion that transcended politics. But Canberra's coup culture helped transform it into one of confusion, comedy and commotion that many Australians would prefer to forget.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external