The pleasures and perils of the open-plan office

- Published

They can be noisy and distracting or depressingly quiet, and frictions with co-workers are guaranteed - so why do so many of us continue to work in open-plan offices?

In the spring of 1962, a fourth-year British architectural student was tasked with sketching an office layout.

In the course of his research, Frank Duffy stumbled across a small article in a trade magazine about a new workplace design that had taken hold in Germany. Accompanying the article was a curious photograph.

"The arrangement of the desks was somehow organic," Duffy recalls. "And there were other features that were striking. There were lots of plants around the place, and a carpet."

The office in the photograph was open-plan, but it was a world away from the open-plan offices with which everyone was then familiar.

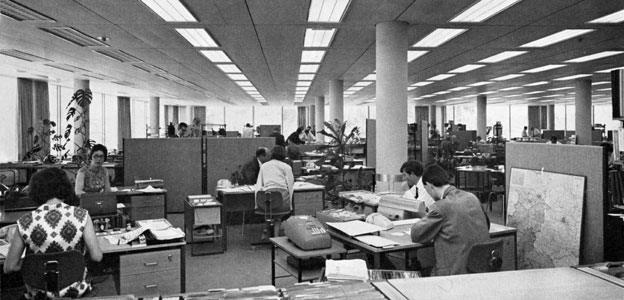

Quickborner's plan for Osram's Munich office, 1965 (photo at top of page)

These had arrived about a century earlier, when architects had started to use cast-iron girders to open up larger spaces within a building. In the American industrial boom of the late 19th Century, bosses jumped at the chance to replicate their beloved factory lines with ranks of pen-pushers.

Clerical workers sat at small desks in straight rows, often facing the same way - a classroom without a teacher.

Those further up the food chain had their own office, and the boss generally had a large corner office with windows on two sides. His lieutenants - usually men - would be despatched to survey the activities of the secretarial pool - usually women.

"The office, especially the North American office, comes in a military, top-down nature," says Frank Duffy. It is no coincidence, he says, that the 20th Century reaction against the top-down office layout started in Germany as "fundamentally a reaction against Nazism".

The concept, devised by the consultants Quickborner, was called Burolandschaft - office landscaping. A glance at a layout chart from that time reveals desks scattered in a seemingly higgledy-piggledy fashion, with desks butting up against each other every which way, and clustered in work zones of different sizes.

In fact, the layouts were anything but random. "The layout was based upon an intensive study of patterns of communication - between different parts of the organisation, different individuals," says Duffy, who became a leading exponent of Burolandschaft.

Whereas in the secretarial pool chatter was frowned upon, the new type of open-plan office encouraged disclosure, discussion and debate.

Managers were mixed in with the masses, cutting down on the expense of managerial offices and allowing organisations to manage their workforce more flexibly. If someone got a promotion, they wouldn't graduate to a new or larger office - they might not need to change desks at all.

But the many millions of people working in this kind of open-plan office today know that there is such a thing as too much communication. Proximity to our colleagues makes it easier to have a spontaneous micro-meeting, but it also means we have to sit through their deconstruction of the previous night's TV, or their shouting matches with teenage children over the phone.

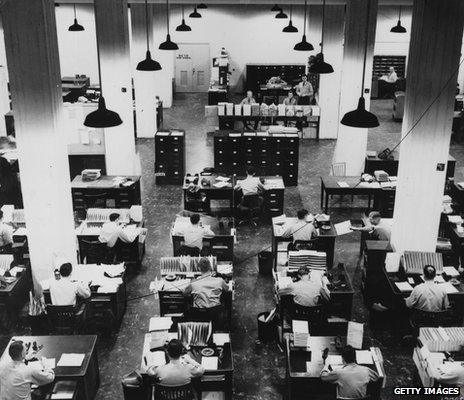

Clerical workers in the Pentagon, 1950

"Nobody can understand two people talking at the same time," says Julian Treasure, chairman of the Sound Agency.

"Now that's key when we're talking about open-plan offices, because if I'm trying to do work, it requires me to listen to a voice in my head to organise symbols, to organise a flow of words and put them down on paper."

If someone else is speaking your "auditory bandwidth" is full, he says, and it becomes very hard to listen to that voice in your head.

A 1998 study in the British Journal of Psychology found that background noise containing irrelevant speech affected workers' ability to memorise prose and do mental arithmetic.

But Alexi Marmot, an architect and professor at UCL University College London, says that although loud background noise probably does affect workers' ability to concentrate, and therefore their productivity, another key question for management is how agreeable the environment is for employees.

And in some open-plan offices, particularly the "classroom" type, there can be too little noise.

"In many open-plan offices, the argument is exactly the opposite - it's deathly quiet," she says. "A lot of open-plan offices are just rows of people only working at their computers. And people don't want to be there."

The quieter the office, the harder it becomes to have confidential or personal conversations. A certain amount of noise seems to be desirable - like the hum of a busy restaurant that allows a table of two to enjoy a private conversation.

Some companies are looking to technology to help get this balance right - broadcasting "pink noise" from speakers (a sound similar to white noise, which makes human speech less discernible).

Open-plan office workers also have other irritations to put up with.

There is the shortage of daylight and the ongoing squabbles with colleagues, over the air conditioning (on or off?) the blinds (up or down), food at the desk, the telephone ring tone...

A 2009 review article published in the Asia-Pacific Journal of Health Management found that 90% of studies looking at open-plan offices linked them to health problems such as stress and high blood pressure.

Although there is some evidence to show that younger employees value rubbing shoulders with more experienced colleagues, it seems that for many the cons outweigh the pros. A 2009 study in Sweden, external found that occupants of private offices were most happy with their environment, while most dissatisfaction was registered in medium and large open-plan offices.

In the 1970s, the "co-determination" movement swept across Europe. Legislation in Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and Italy gave workers a say in how companies were run and offices were designed.

"That led ultimately to the rejection of office landscaping in Germany and in Scandinavia," says Frank Duffy. Northern European office buildings today are "highly cellular", he says, with everyone having "the right to a window they can open, a door they can shut and a wall they can beat upon".

In his 2000 book The European Office, Juriaan van Meel noted that in Sweden "almost everybody has a private office", while in Germany "open-office layouts are scarce" - although small teams sometimes shared a room.

German office workers have an average 28.2 sq m of personal space. Their right to elbow room and daylight is enshrined in law.

The office buildings that meet such requirements generally have separate wings of long corridors, with small offices on either side. Some, the most ambitious, have a central "street" where employees can come together to collaborate.

In the UK and North America, by contrast, design is mostly driven by cost rather than worker satisfaction, and open-plan layouts remain the norm.

In London's West End, space for one desk (4 sq m) costs £8,500 ($13,000) a year. A private office would cost much more than that - and have a larger carbon footprint.

One compromise popular in the US is the cubicle, in which desk space is enclosed by canvas-covered dividers, usually around 5ft (1.5m) high. It's a set-up which blocks daylight and, supposedly, office distractions.

Another joy-filled day in a cubicle office

But Duffy describes the cubicle-style layout as "a disease, a pathology of the office", which has infected thinking about the workplace across his 40-year career.

"It doesn't give you privacy, it doesn't give you control over your environment," he says.

Chairs and desks are now more adjustable, but the basic layout - cubicles aside - of many North American offices has not altered much in 100 years. Many people are still sitting together in a large room at separate desks, and still aspiring to that big corner office.

For Alexi Marmot, office layout shouldn't be a compromise between private and public space, but one which offers both things to its employees whenever they need them. She gives the analogy of soloists in an orchestra, who need to spend hours practising alone before coming together to rehearse and perform.

Her vision doesn't include rows of desks - in fact, it might not include any desks at all.

"We know from what young people are telling us that they prefer much more free-flowing places," says Marmot, "the idea of hanging about anywhere with your laptop and various other mobile devices, with coffee in any posture you care to have - not necessarily on a five-star chair."

She describes a building she visited in Switzerland which offered workers a choice of sofas, coffee table areas, libraries, pool-style recliner chairs and even "a botanical garden with a few work tables among the plants".

But to give employees the freedom to wander about with their laptops, hiding from colleagues or seeking them out as they wish, may mean some organisations have to rethink the way they work and communicate.

"The building's easy, the architecture's easy," says Duffy. "It's thinking about how to use the buildings that really is challenging."

You can listen to The Why Factor on the BBC World Service. Listen back to open plan office episode via iplayer or browse the Why Factor podcast archive.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter , externaland on Facebook, external.

Thanks for all your comments.

In my career based in London and then Oslo, I have experienced all types of office solutions - from the converted factory near Paddington (open plan with a few offices) in the early 70s, to a former Edwardian residence converted to offices in Bedford Square (were I had a 4th floor attic office - former servant's quarters I imagine), and then in Oslo in the late 80s to a purpose-built, one-floor solution but with individual offices (very good), and then finally to a "modern" open plan solution - individual desks on two floors but with meeting and "quiet" rooms. What to me has been noticeable is that there was much more and better communication between staff with individual office solutions, and a deathly silence of open-plan in a larger open plan office. Quite the opposite of what managers expected. As human beings we apparently need our own private space to which others can be invited... Peter, Oslo, Norway

I have to agree that open plan offices are a very mixed bag. Since most jobs involve an ad-hoc mix of tasks some of which require total concentration and no interruptions it's far better to give people the option of working in a communal environment OR working somewhere quiet. This can be via working at home when agreed, or perhaps by providing specially constructed quiet rooms. I know from my own experience (and from observing and managing others) that when this option is provided, people's productivity, creativity and job satisfaction can soar. People stuck in an open-plan hell get run down, depressed and demotivated. Open plan offices may be cheaper to set-up, but they deny companies the full use of the human capital they are paying for - so they are a crazily false economy. They are an anachronism from a time when all that was measured was "employee time in the office" rather than the more useful results-oriented measures of today. Alan T, Camelford, Cornwall

Sadly like many things today, the "one size fits all" approach often pushed by academic pundits in their ignorance of day-to-day business activities completely ignores the complexities of competing working requirements. If I can give just one example, as the manager of a computer department, it was essential that my staff were housed in two separate enclosed areas - one for the data preparation and computer operations staff where noise was inevitable, and the second for the systems and programming staff who needed a quiet environment in which to concentrate and create. Eric Jackson, Valencia, Spain

I worked almost exclusively in 'open plan' office environments from the early 1980s until 2010. On the whole the experience was positive and the levels of communication, integration and cross-pollination of ideas that resulted certainly had significant positive effects. However, the chatter and babble that I had to endure at times resulted in me keeping a pair of chain saw ear-defenders to hand - I was able to don said ear-wear when I needed to have the peace and solitude that the complexity or quantity of work demanded. It resulted in some low levels of scorn from colleagues, but that was of no consequence. What was interesting was that even though I could still hear most office sounds (like the phone ringing) through the ear defenders, the very act of wearing them gave off a subtle 'go-away-I'm-working' vibe that allowed others to ignore and exclude me without being impolite ... it worked for me! Richard Thresh, Northwich, United Kingdom

I have to share an office with someone who is very vocal and loud much of the time, particularly when on the phone. This makes concentration very difficult for me. Moreover, when I'm on the phone, she talks over me. In previous jobs, being in an open-plan office has not really been a problem , but at this point I would give my high teeth for an office of my own as I would certainly be more productive. Anonymous, Solihull, West Midlands

Some of my colleagues at Griffith University will soon be moving into a prestigious new building. Only some will be able to enjoy a private office, while others will work in an open plan environment. I have been exploring the reasons given by academics for holding on to their private offices and they include: I need private space to meet with students who might become tearful; I need a quiet space in which to think and write; I have confidential research material; I need space for my personal library and if all else fails...I'm a professor, goddammit, I deserve an office of my own. We appear to be one of the last professions to get away with these reasons in the face of an overwhelming need to save money on space costs. Paul Burton, Tamborine Mountain, Queensland, Australia

As a software and hardware designer specializing in embedded control systems I found that the classic USA cubicle office arrangement generated intense stress due to the almost continual hubbub, noise and other interruptive mechanisms. My work required deep concentration and I am positive that I would have been a far more efficient worker had I had a small office with a door that I could close when I needed to concentrate. Eardley Ham. Woodbury, MN USA

No mention of an increasing habit of workers cocooning themselves by wearing headphones and listening to music. Beats me how they can do creative work (as opposed to repetitive work) and still think! Also annoying when you ask them something without realising they are oblivious to your voice because they have those small ear phones that you hadn't noticed. I've been in all sorts of offices in my life and prefer an open room big enough to hold a team so that there is interaction and team cohesiveness and ability to foster better ideas . Cubicles are dire - cut off from daylight and the world. Small office can be like a prison especially if there is an obnoxious fellow worker. Hot desking with the different mood areas described in the Switzerland example look good. Alan Cooper, Trowbridge, UK

The essential ingredients of good open-plan office acoustics are evenly distributed sound-absorptive materials and a minimum level of background noise throughout. The background noise should consist of unintrusive non-characteristic noise. Pink noise generally achieves this, but it must be correctly tuned (equalised) by an expert to ensure it cannot be obviously perceived by the occupants. Tim Nicholls, Melbourne, Australia

I work in the civil service and, due to the sell-off of one of our main sites and squeezing everyone into remaining sites, there aren't enough desks for all. So our workplace has introduced a "flexible desking" system - no one has their own desk anymore (so no personalisation possible), and we have to book our desks in advance. It is assumed not everyone will be in on the same day due to customer meetings, etc (this isn't always the case, depending on time of year!). It can be a nightmare if you need to find a colleague in a hurry as we have large open plan areas. We have a technical ('smart') phoning system in place where people have their own personal numbers which they log in against their desk...but many people have problems with this, or forget to log out. Anon, Fareham, Hampshire

This is the bane of my life! For 25 years I shared an office with just one other colleague. Last year, the admin team were brought over to our location due to their building lease coming to an end. As a result, our existing office area was redesigned to become open plan as it was the only way everyone (20 people from the other building) could be accommodated. It was also the cheapest solution. Let the arguments begin - No one can agree on the radiator settings. Those closest to the windows complain of draughts. Those further away complain of it being stuffy. Lighting is a problem as the controls are too general. Smelly food at lunch time is banned because people complain about what others eat. Noise is a major problem. Apart from the obvious "talking" hum drum you get, the photocopier and fax machines are right behind me. You literally cannot hear yourself think at times. Also being open plan has dramatically increased the number of interruptions you are subjected to. It is near impossible to have a private conversation now. I've resorted at times to going to my car to discuss sensitive issues. I long for my little office to come back with that wonderful invention called the door..... Steve Isaacs, Altrincham, Cheshire