Has Street View changed the way we behave?

- Published

Google's Street View cars have driven millions of miles, picturing the streets and landscapes of 39 countries. But while many people use its 3D maps to look at the places they already know, has it also changed the way they relate to the wider world?

Drag and drop Google's little orange man onto a map of the street where you live and there is a good chance that you will find your home.

Move the figure along the surrounding roads and you can find the shop where you buy your milk, the pub where you drink and maybe a neighbour or two - their faces blurred to provide a semblance of anonymity.

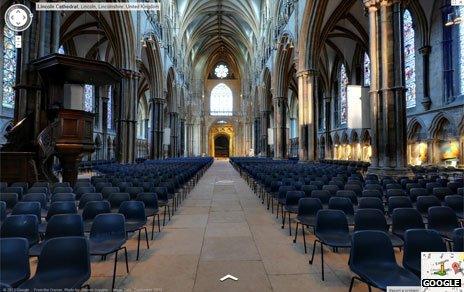

Google's Street View cars have now driven 65% of the UK's roads, including Shetland, the Isle of Wight and much of what lies in between. The interiors of some museums, cathedrals and - increasingly - shops can also be explored.

Further afield, the snow-fringed roads of Longyearbyen on the remote Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, and the coastal town of Bluff, in southernmost New Zealand, can be navigated without ever visiting.

From the most northern spot of Norway...

And although the project hasn't won over everyone - including 250,000 German households who asked for their homes to be pixelated - the plan is to continue adding locations. Google says it would "love" to map China.

But other than providing an opportunity to have a nose around during idle moments, has Street View made any difference to the way people live?

A clue is provided by John Haas, a lecturer from Northwestern University in Illinois, who is "not into surprises".

Ahead of a work trip to Paris he spent evenings on Street View "touring the streets" around the hotel where he would be staying.

"We're about four or five blocks away from the Eiffel Tower... I could chart a path, I could see what's along the way for coffee, restaurants and shops," he says.

... to the southernmost tip of New Zealand

Previously, Haas would have turned to guidebooks to provide the information for a successful trip.

But he feels that being able to see the outside of a hotel, the surrounding city and its inhabitants is an entirely different experience.

"It's definitely changed the way I would approach travel... I look at Street View first to see where I'm going, what's around me."

And it is not the first time he has used it to eliminate uncertainty.

"If I'm going to a friend's house for a dinner party I check whether there's parking on the street, so I know if I'm driving, or if I can take a cab."

The ability to become immersed in a map offers many other uses that a traditional street plan can only hint at.

Tradesmen - including glaziers and satellite dish installers - can look at a property online and talk to potential customers about their services without actually visiting. Drivers can find landmarks to make unfamiliar car journeys easier; and architects can study buildings without being there.

Other users highlight the opportunity to peek at a friend or colleague's house, the ability to bring the locations of books to life, the chance to revisit childhood haunts and the option of investigating a pub or restaurant before agreeing to meet friends there.

Less happy are those whose homes are pictured with the bins out, or before there was a chance to re-paint the peeling garage door.

But it's these clues to a neighbourhood - and its homes - that appeal to house hunters.

"Without it I think we would have been driving round, area to area," says Curt Parks, who is looking for a four-bed detached home in Berkshire with his partner, Denise.

Although between 40 and 50 houses looked good in the estate agents' details, they have only bothered to visit four or five after walking past the others on Street View.

"We were looking at one that looked lovely," he says. "You go into Street View and you realise that it's on a main road and at the end of a grotty row of houses."

The refined search means more time with his son: "We're saving weekends. The last thing I want to do is spend our time traipsing round."

Even greater use of 3D mapping for these tasks and others is "inevitable" in the future, according Prof Jerry Brotton, author of A History of the World in Twelve Maps.

"Maps will always endure, they will just have a different form. The paper map is basically in decline," he says.

While there are unresolved questions over privacy, who owns the data behind digital maps and whether people can opt in - or out - of appearing on them, they will "redefine what we do" says Prof Brotton.

They will also be "what we look back at historically" when - at some point - we want to see what the streets of 2013 looked like.

Lincoln Cathedral's interior can also be seen on Street View

Street View has already changed the way people get to know places and "how we interact with the physical world", says Prof Andy Miah, director of the Creative Futures Institute at the University of the West of Scotland.

Users turn to it as an "expanded guidebook" and in doing so start to understand their environment in a different way, he says.

As people increasingly rely on Street View they can find themselves experiencing the real world through a screen - instead of by looking around them - and begin "thinking about it as a digital environment", he says.

That can be disappointing, if not confusing, as its pictures are often out of date and a place might not be as expected, he says.

Nevertheless, the virtual visit - along with the real one - can be part of how they remember somewhere.

"Our memory of the place may become inextricable from that virtual experience," says Prof Miah.

Not everyone is convinced that the changes brought by Street View are wholly beneficial.

Although he accepts the application's many practical uses there is also a downside, says Dr Alexander John Bridger, a psychology lecturer at the University of Huddersfield and founder of the town's psychogeographical network, external.

Street View users can "lose that experience of where they are and it just becomes a very automatic 'I need to get from here and I need to get to here'... so it becomes a routinised mechanistic way of behaviour", he says.

"I think it does prevent those chance, coincidental moments from happening."

Arriving somewhere and relying on your senses, or conversations with strangers, can be much more rewarding, he says.

It's the old fashioned way.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external