The people who think they tune into dead voices

- Published

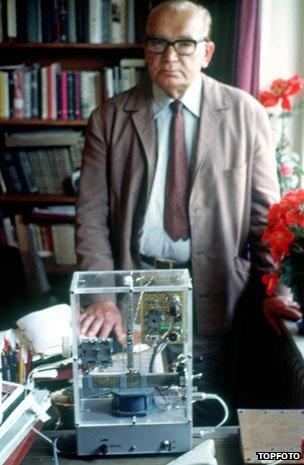

Konstantin Raudive and his EVP device

Advocates of Electronic Voice Projection (EVP) claim they can use radio equipment to communicate with the dead. But are they just hearing what they want to hear?

In 1969, a mysterious middle-aged Latvian doctor turned up in Gerrards Cross with a large collection of tape recordings.

He had, he said, been conducting experiments in communication with the dead, and had established contact with Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini and many other deceased 20th Century statesmen. The recordings - 72,000 of them - contained their voices.

His name was Konstantin Raudive, and he called his technique Electronic Voice Projection, or EVP.

It wasn't real-time interactive communication. You asked your questions, and then left the tape running, recording silence.

But listening back, through the mush and static, you could sometimes just about make out people speaking.

Gerrards Cross was the home of a publisher, Colin Smythe, whom Raudive hoped would publish a book on his findings.

Smythe was keen, but he needed to persuade the chairman of the publishing company, Sir Robert Meyer, that this wasn't all a hoax. So Raudive laid on a series of electronic seances in Gerrards Cross, one of which Sir Robert attended.

As luck had it, the late pianist Artur Schnabel was on the line, and spoke - at least to the satisfaction of Lady Mayer, who was also present and had known Schnabel. The book, called Breakthrough, went ahead, and EVP was on the scene.

More technologically up-to-date than spirit slate-writing and less messy than ectoplasm, it dragged the world of spiritualism into the late 20th Century.

Nowadays, EVP is a standard tool of ghost hunters worldwide. There are hundreds of internet EVP forums and many serious and well-educated people who see it as proof positive that the dead are trying to talk to us.

For example, Anabela Cardoso, a former Portuguese career diplomat who lives in Spain and publishes the Instrumental Transcommunication Journal, external. She has a well-equipped recording studio and claims to have replicated the Gerrards Cross findings.

"My voices are not little voices," she says. "They are loud and clear and totally understandable." She offered to send me a CD.

Meanwhile, Smythe is still living in Gerrards Cross.

Raudive had wanted us to believe that Hitler spoke to him in Latvian, not a language he ever mastered while alive. He said things like "kindle willingly", and "you are a girl here, or else you are thrown out".

I put it to Smythe that these were surely not the kind of utterances we associated with the Fuhrer. But, he points out, it could be identity theft.

"A communicator is not necessarily going to be truthful. They could be using the names of famous people in the hope of that they will be taken notice of."

So what happened to the Raudive tapes?

In a store room in Smythe's house, almost impossible to get into for boxes, we finally found seven quarter inch reel-to-reel tapes, probably unplayed for four decades. And on one was Raudive, summoning up the dead.

According to a book published at the time by Smythe's partner, a Russian voice at that session said "Stefan is here. But you are Stefan. You do not believe me. It is not very difficult. We will teach Petrus." But on the tape there was nothing, just hiss.

On another occasion, the broadcaster Gyles Brandreth was present when Raudive produced the voice of the late Winston Churchill, speaking what everyone present agreed were words from Land of Hope and Glory. "It was, credibly, Winston Churchill," Brandreth remembers.

Churchill: 'recorded' speaking lines from Land of Hope and Glory

But when we listened together to the tape, he had to agree that it sounded nothing like Churchill - it was far lighter than the familiar gravelly voice. "Maybe it's the young Winston," Brandreth suggested. "Or a Churchill impersonator?"

But who impersonates the young Churchill? We couldn't think of anyone.

The voice of Churchill? Judge for yourself...

When Cardoso's CD arrived I was disappointed that the voices, in Spanish and Portuguese, were not really very clear. According to her translations, they said things like "There is a rabbit on your head". But Dr Cardoso was, like other EVP investigators, definitely recording voices.

So what's going on?

The simplest explanation is that EVP voices are just stray radio transmissions. Usually they are so faint and masked by static interference that it's hard to make out what they are saying, and the EVP investigator has to "interpret" them for you.

That might seem like a weakness but that's also their power. As Joe Banks, a sound artist, points out, a dead person speaking in studio quality wouldn't be nearly so convincing as a voice you must strain to hear.

Banks has an ongoing project called Rorschach Audio. He suggests that the voices are the aural equivalent of inkblot tests devised by Swiss psychologist Hermann Rorschach. He argues that while the EVP experimenters think they are doing parapsychology, they are actually unwittingly carrying out psychology experiments.

For example, if you take recorded speech and replace every sixth of a second with white noise, the speech is still comprehensible. But if instead of white noise you use silence, it's much harder to understand.

We are naturally well-adapted by evolution to imaginatively reconstruct speech against a noisy background - imagine trying to whisper in a windy forest to your hunting companions.

EVP enthusiasts, Banks thinks, aren't idiots. They are just being fooled by audio illusions that take us all in.

But once you start experimenting with EVP, it's hard to stop. After Breakthrough was published, Raudive progressed from voices captured on tape to voices coming from animals, in particular a budgerigar named Putzi, who spoke in the voice of a dead 14-year-old girl.

Similar work today is being done today by EVP researcher Brian Jones in Seattle.

He records the noises made by seagulls, dogs, cats, and even squeaky doors and crunching pebbles. They all contain voices. One dog says, "Where's Sheila?" referring to its owner. Another complains of its owners, "they always sail away".

Jones thinks he can capture thoughts that somehow are in the air. "I have documented a lot of things that are pretty stunning that way," he says.

He would like to use his techniques to help solve crime, or to pick up the thoughts of stroke victims who have lost the power of speech. So far, he has been shunned by private detectives and doctors.

But the EVP community really want to believe they are onto something. And many of us find the idea of communicating with the dead so tantalising, so appealing, and yet so elusive that it's easy to see how normal psychological mechanisms can be co-opted into making us believe in the unbelievable.

Out of the Ordinary was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on Monday 25 March at 11:00 GMT - catch up on iPlayer

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external