Viewpoint: Why do tech neologisms make people angry?

- Published

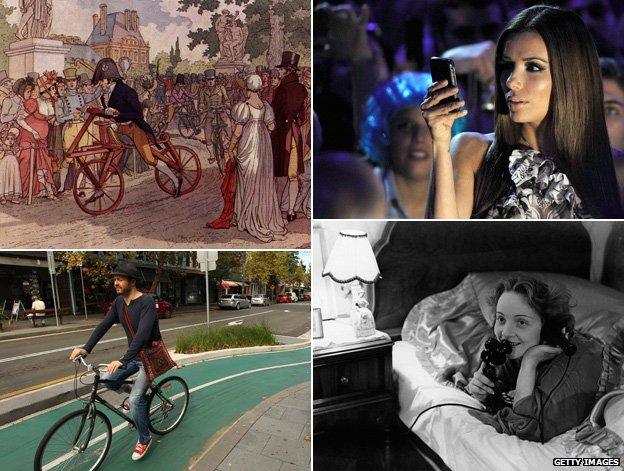

From velocipede to bike, and telephone to smartphone

The bewildering stream of new words to describe technology and its uses makes many people angry, but there's much to celebrate, writes Tom Chatfield.

From agriculture to automobiles to autocorrect, new things have always required new words - and new words have always aroused strong feelings.

In the 16th Century, neologisms "smelling too much of the Latin" - as the poet Richard Willes put it - were frowned upon by many.

Willes's objects of contempt included portentous, antiques, despicable, obsequious, homicide, destructive and prodigious, all of which he labelled "ink-horn terms" - a word itself now vanished from common usage, meaning an inkwell made out of horn.

Come the 19th Century, the English poet William Barnes was still fighting the "ink-horn" battle against such foreign barbarities as preface and photograph which, he suggested should be rechristened "foreword" and "sun print" in order to achieve proper Englishness.

Forewords caught on, but sun prints didn't, instead joining the growing ranks of outmoded terms for innovations - a scrapheap that by the end of the century ranged from temporarily mainstream names like velocipede (meaning "swift foot" and used to describe early bicycles and tricycles) to near-unpronounceable curiosities like phenakistoscope (an early device for animation, meaning "to deceive vision").

I've spent much of the last year writing a book about technology and language and, today, the debate around what constitutes "proper" speech and writing is livelier than ever, courtesy of a transition every bit as significant (at least so far as language is concerned) as the Industrial Revolution.

From text messages and email to chat rooms and video games, technology has over the past few decades brought an extraordinary new arena of verbal exchange into being - and one whose controversies relate not so much to foreign infiltrations as to informality, abbreviation and self-indulgence. Hence the swelling legions of acronyms (LOL!), grunts of internet-inspired indifference (meh) and social-media-inspired techniques for dramatising the business of typing (#knowwhatImean).

In each case, the dividing line is largely generational - with a dash of snobbery and aesthetic appeal thrown in. Yet even the most seemingly obvious divisions between old and new can break down under closer examination.

When the Oxford English Dictionary took the leap and added some "notable initialisms" to its vocabulary in March 2011 - including "oh my God" (OMG), "laughs out loud" (LOL) and "for your information" (FYI) - it noted that OMG had first seen the light of day in a 1917 letter from a British admiral to none other than Winston Churchill.

Even that most iconic embodiment of online messaging, the emoticon - a happy or a sad face drawn in punctuation marks - was pre-empted by a satirical 19th Century magazine called Puck under the heading "typographical art".

Yet it would be perverse to pretend that there's nothing unusual about the age of the internet, not least in the move away from spoken words as the driving force behind linguistic change, and towards the act of typing on to a screen. We've already grown so used to saying phrases like dotcom out loud that we forget we are speaking punctuation marks.

Some words even make use of common typos in order to indicate shades of meaning - the "internet z", for example, which features in mis-spellings like lulz to denote a specific online culture of digital disorder, or the entire idiolect known as lolspeek, most often found in association with captioned images of cats (it's also sometimes called "kitty pidgin").

Speed of communication today is matched by the speed with which new words are taken up. Bicycles, automobiles and telephones took decades each to become a part of daily life, both as words and as objects.

With online offerings, success can girdle the world in a matter of months. When I first heard tweet as a term, I sneered. Now I accept it, just as the verb "to Google" has become a part of dozens of languages across the world. Where habit leads, language follows.

For the first time in human history, moreover, a majority of the world's adult population are playing an active role in the culture of reading as well as of writing. Social media networks are a particular engine of change, not least because what they offer is effectively an arena of typed conversation. Within them, written words spill out at the speed of speech, together with the peculiarly binary formulations that digital sociability involves:

to friend and to unfriend

to follow and to unfollow

to like and to unlike.

While friend/unfriend and follow/unfollow may embody corporate coinages at their most reductive, there's a freewheeling creativity to word-building at the user end of social media.

If I meet my social media followers in real life, I'm indulging in a tweetup - that is, a meetup for tweeps (a contraction of "twitter peeps", itself a contraction of "Twitter people").

If I can't drag myself away from this particular social media service for even a moment, I may be a borderline twitterholic - although my fluency in speaking twitterese will be hard to dispute by anyone else in the twittersphere. I may even win the approval of the elite twitterati, so long as I don't embarrass myself by sending dweeps (drunken tweets).

And if you think all these words are unworthy of note, the Oxford English Dictionary disagrees with you.

It's far harder in some languages than others to import or invent vocabulary, of course. The Chinese character-based writing system entails constantly pressing old symbols into new service.

The word for a computer, for example, involves combining the characters for "electric" (dian) and "brain" (nao), while the character for "electric" itself originally denoted lightning.

It's a feature that makes fluent literacy in Chinese characters extremely challenging - and creates an internal consistency that many elsewhere would welcome. For, just as it was in the 16th Century, language change is a potent proxy for other concerns - about globalisation, the undermining of regional cultures and values, the decline of a shared sense of what is "proper" - and the stuff of thought itself.

Consider a particularly cumbersome tech neologism - gamification - meaning the use of principles derived from video games to make another experience more engaging.

Foursquare, a social network in which users "check in" when they arrive at favourite hang-outs, is an example of gamification

In his recent book To Save Everything, Click Here, author Evgeny Morozov offers a blistering critique of both the term gamification and the mentality it encodes - the notion that almost any human activity, from voting to recycling, can be mechanically restructured like a game and thus made "fun".

As he puts it: "Soviet planners were also gamification enthusiasts, even if they never used the term." Their preferred label was "socialist competition", and the "games" they arranged involved unending, repetitive labour rewarded by empty titles - not entirely dissimilar to using some online services today.

If change must not be confused with progress, however, it's equally a category error to equate it with decay - not least because the changes currently taking place to language online are far too expansive either to summarise or condemn.

One of my own favourite neologisms is the Cupertino effect - which describes what happens when a computer automatically "corrects" your spelling into something wrong or incomprehensible.

The name originates from an early spellchecking program's habit of automatically "correcting" the word "cooperation" (when spelt without a hyphen) into "Cupertino", the name of the California city in which Apple has its headquarters.

One of my favourite Cupertinos was my first computer's habit of changing the name "Freud" into "fraud" - or, more recently, of one phone's fondness for converting "soonish" into "Zionism".

As Cupertinos suggest, onscreen language is both a collaboration and a kind of combat between user and medium. And if self-expression can sometimes be reduced to little more than clicking on "like", there's every bit as much pressure exerted in the opposite direction.

If you can do it, someone, somewhere has probably already coined you a term - from approximeetings with friends (arranging a rough time or place to meet, then sorting out details on the fly via mobile phone) to indulging in political slacktivism (ineffective activism carried out by clicking online petitions).

Only time will tell what endures. For digital natives and immigrants alike, though, there's much to celebrate in the constant flux of our tongue - not least in the reminders it offers of the human stories beneath even the most seamless of technology surfaces.

If the history of language teaches us anything, it's that logic and reason come after the event with words - and that we are always saying more than we intend.

Tom Chatfield is the author of Netymology: A Linguistic Celebration of the Digital World

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external