Musulin and Cahuzac: France's love for a robber and fury over a crooked tax tsar

- Published

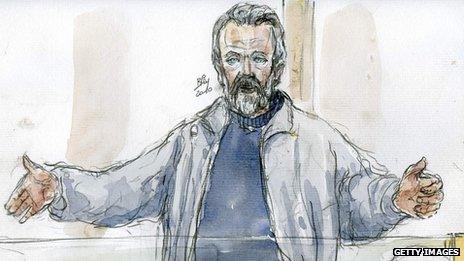

Folk hero: Toni Musulin sketched in court, in 2010

A film released this week tells the true story of a robber who stole millions of euros from an armoured van. Many French people feel he was treated too harshly - and are furious that senior politicians who break the law are never jailed.

As folk heroes go, Toni Musulin makes an unlikely candidate.

A middle-aged security van driver, neither handsome nor charismatic, he said little and was notoriously tight with money.

He felt trapped in a dead-end job, ground down by petty bosses, and believed he deserved better.

Despite his low pay, he managed to buy himself a second-hand Ferrari, but kept it secret from his workmates and continued to cycle in every morning.

Musulin appeared to be a model employee, always punctual and hardly ever off sick, but one day four years ago he stepped out of character.

He waited until his two co-workers had got out of the van, and suddenly drove off with €11.6m (£9.9m) from the Banque de France.

Newspapers dubbed it the heist of the century and, far from being condemned, he became a legend.

Not just a loveable rogue in the way that some view the UK's Great Train Robber, Ronald Biggs, but a symbol of the small man who struck back at big business - and unlike the train robbers, he had not resorted to violence.

At a time of public rage over ruinous bankers, rising unemployment and political corruption, Toni Musulin was celebrated in a pop song and seen as a Robin Hood figure.

In 2010 he was jailed for three years by a court in Lyon.

A sympathetic film about his exploit came out in France this week - on the same day the government was plunged into crisis by a former minister's bombshell confession that he had squirreled away €600,000 (£510,000) in illegal offshore bank accounts.

I went to see the film the day after Jerome Cahuzac - the very man President Francois Hollande had put in charge of a campaign against tax fraud - admitted he had cheated on his own taxes.

The cinema audience broke into applause when Musulin grabbed the booty.

Everyone seemed to be on his side - against the banks, against the multinationals, and against politicians who had been quick to censure the likes of Gerard Depardieu, the actor who says he left France to escape high taxes.

The film ended with a rap song praising Musulin for taking the cash without harming anyone. As the lights came up I saw smiling faces all around me.

I asked a few people what they thought of him.

"What he did had to be done," one woman told me.

The man next to her gave Musulin the thumbs up but said he could not comment because he worked for a bank.

Jerome Cahuzac: Gamekeeper and poacher

Even in a country inured to sleazy politics, the revelation that the fiscal gamekeeper had been a poacher all along has taken outrage to new heights.

People feel doubly cheated because President Hollande came to power less than a year ago, promising to clean up French politics.

Now he risks becoming a lame duck, and more damage has been inflicted by news that the man in charge of his own campaign finances last year has investments in the Cayman Islands, a known tax haven.

As for Musulin, he has spent years in a prison cell, whereas no senior politician found to have broken the law has ever been jailed.

When the former president, Jacques Chirac, was convicted two years ago of misusing public funds, he got a prison sentence but it was suspended. French people now want to turn the page on a culture of impunity.

The young, especially, tend to compare French politicians unfavourably with their counterparts in Britain, Germany or the United States.

Many believe politicians are guilty of worse wrongdoing than Musulin, who has nearly served his time.

His lawyers hope he will be released by the end of the year, but his story is not over yet.

Of the money he stole, €2.5m euros (£2.12m) has never been recovered. Police found the rest in a garage and they suspect he left it there deliberately and hid the rest elsewhere.

Musulin insists he left it all in the garage and claims to have no idea what happened to the missing cash.

Police found some of Musulin's haul in a garage but the rest is still missing

But investigators believe he planned everything from the beginning, and that is why he walked into a police station and calmly gave himself up after less than two weeks on the run, knowing he could only be jailed for a few years for a robbery without violence.

A public prosecutor has vowed to keep chasing him after he is freed.

If he manages to catch him with the loot, there will most likely be a lot of rather disappointed people in France.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external