Mexico's vigilante law enforcers

- Published

Linda Pressly meets the vigilantes fighting Mexico's criminal gangs in Guerrero State

Insecurity dominates the lives of millions of Mexicans. Caught between the murderous drug cartels and absent or corrupt law enforcement, communities are taking the law into their own hands. In the state of Guerrero, a fledgling vigilante force has grown into an organisation numbering thousands.

In the market town of Ayutla on a sweltering afternoon, two rusty old saloon cars pull up outside a furniture store on a street corner. Men with their rifles pointing skyward tumble out of the vehicles.

But one of them has no gun. Nor does he have any shoes. He is being detained, and is brought in roughly by the men with weapons - all volunteer members of Ayutla's self-defence force.

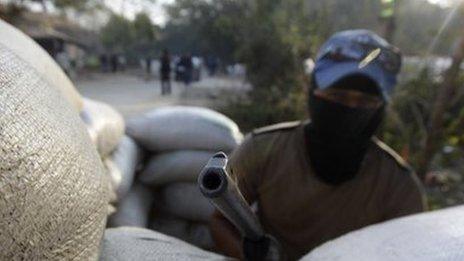

This street corner is the group's makeshift, unofficial headquarters. There are a few old chairs, a table, a barrel and some sandbags. Behind them, wardrobes embossed with Disney princesses jostle with chests of drawers. The young man with no shoes has his hands tied behind his back with nylon rope, and is told to sit down.

"We're not going to mistreat him, or be aggressive with him", explains Leonides Ramos Ortiz, a member of the self-defence force. "We're going to take care of him until the investigation begins."

Since they became a force to be reckoned with earlier this year, this is just one of dozens of arrests made by untrained, armed civilians from Ayutla and its surrounding pueblos. But they have no legal authority, and they should not be carrying their guns in the street.

This does not seem to be of concern to the steady stream of locals who come to the HQ to report crime. Dona Juana, a frail elderly woman, is having problems with a neighbour. He is trying to steal her land.

"He says he's going to tie my husband up and drag him behind a horse, he's going to kill me, and kidnap my daughter", she says.

Dona Juana has been to the police, the local council and the public affairs ministry, and nothing has been done.

Her friend, Carmela, believes Dona Juana's only hope is the "community police" as she calls the self-defence force.

"The regular police and the military are all being used by organised criminal groups to carry out their activities. They're not stopping crime. Now we have our own community police, everything is much quieter. In the last couple of months organised crime has begun to disappear."

Guerrero is what is called a hot state. It has some of the most violently disputed territory in Mexico, and produces more than half the country's heroin.

Drug cartels grow opium poppies and marijuana in the highlands of the Sierra Madre, and move cocaine towards the United States along the state's mountain passes. Acapulco on the Pacific coast is the Mexican city with the highest homicide rate.

And murder is a regular occurrence in Ayutla. On the outskirts of the town, down a rough track, a cavalcade of armoured military vehicles and police pick-up trucks have come to a stop next to a small farm.

Around the perimeter of the property, members of the self-defence force have taken up positions at five-metre intervals. Yellow police tape cordons off one area.

"They found the remains of a body here, in an unmarked grave. It looks like it's a drug-related crime", says Gonzalo Torres, a large middle-aged man in a checked shirt, and one of the vigilantes.

"Local people told us about the body, and we gave that information to the police." This is a role the self-defence force would like to play - important intermediaries between the community and Mexican authorities that are often regarded with suspicion by locals.

The next day another three bodies are found close by. One of them was buried crouching, a young man with his legs tucked under his chin.

Kidnap, too, is a common crime in Ayutla, a profitable sideline for the drug cartels and organised crime. Everyone knows someone who has been taken.

In January, when the third of their commanders in as many months was bundled into a vehicle by an armed gang, hundreds of men, and some women, joined the self-defence force. They swooped and detained more than 50 people they claimed were guilty of serious crime.

Comandante Ernesto Gallardo Grande denies allegations of torture

Eleuterio Maximino Flora was the first vigilante commander to be abducted. He did not think he would get away alive.

"They said they were going to kill me. They kicked me, and used torture. They nearly drowned me."

He says he did not know the men who held him. But he does know why he was taken.

"We had detained some criminals. So the gang kidnapped me to use as a bargaining chip to get their people released. I was freed after Comandante Ernesto Gallardo Grande told them if they executed me he was going to kill 10 members of one of their families."

But in this scary scenario, who were the bad guys? It is an illustration of what can happen when organised crime, an armed population and a power vacuum conspire to create an altogether toxic mix.

And there are allegations of torture against the self-defence force too. Rafael Mendoza Ventura is a lawyer representing some of those who were detained by the vigilantes in January, and who are now in the custody of the state while they are being investigated.

"While they were held by the self-defence force, electric shocks were applied to genitals, there were beatings, plastic bags put over detainees' heads - the same kind of practices the police use to extract confessions."

Ayutla's self-defence group found this man guilty of violence against his wife

Comandante Ernesto Gallardo Grande denies these allegations.

Citizens' self-defence groups are now operating in 13 Mexican states. According to one newspaper, Reforma, they are present in more than 60 municipalities. But there are wider concerns about the growth of the vigilante movement in Mexico.

Luz Paula Parra is a security expert at CIDE, Centro de Investigacion y Docencia Economicas in Mexico City, and believes the state must take action to stop it.

"In Ayutla, it's very dangerous, a very short-term gain to allow these groups because they will be Frankensteins. Little by little they will gain power and resources, and then it won't be easy to stop them."

She points to examples elsewhere in Latin America, like Colombia, where self-defence groups morphed into paramilitary killing machines during the civil war.

And what of the shoeless young man detained in Ayutla, tied up and investigated? Even though the self-defence force found him guilty of violence against his wife, he was not handed over to the police.

Instead he was put to work sweeping streets and painting houses - part of a system of punishment and rehabilitation with its roots in indigenous culture, passed down from Mexico's original inhabitants.

At the end of last month, in their largest show of force so far, more than 1,500 of Ayutla's self-defence volunteers surrounded the community of Tierra Colorada. They demanded the police arrest several officials after one of their volunteers was murdered.

This is a movement that is growing in confidence. The risk is that it becomes yet another unaccountable, organised, armed group - one that threatens rather than enhances the security of the citizens of Ayutla.

- Published27 March 2013