Margaret Thatcher and the taboo of speaking ill of the dead

- Published

Margaret Thatcher's death was greeted by a torrent on Twitter and elsewhere. The battles that broke out between those showing loathing and those demanding respect shows the taboo over speaking ill of the dead is still powerful.

Yesterday a flood of tweets greeted the death of Margaret Thatcher.

One of the most curious strands in the early comments was tweeters predicting that there would soon be abusive tweets.

There soon were.

Some - including Respect MP George Galloway and comedian Mark Steel - tweeted references to Elvis Costello's song Tramp the Dirt Down. Released in 1989, the song imagines the prime minister's death and going to her grave where "we'll stand there laughing and tramp the dirt down".

It was seconds from the first tweet revealing the news to the first abusive tweet. Within minutes, news of her death was trending under at least three hashtags, and soon some that hinted at disrespect (#nostatefuneral and #nowthatchersdead).

News and humour website Buzzfeed noticed the outpouring, external of the vitriol was so widespread people were even making the same joke "ding dong the witch is dead", a reference to the song from The Wizard of Oz.

Others looked forward to parties they said would take place the same evening. Comedian Ross Noble regretted he was in Australia as he did not like to miss a good street party. Some called for milk parties. True to the tweets, last night saw parties in places like Glasgow and Brixton in south London. There were reports of cheers among a minority at a National Union of Students conference.

Then there were lots of people who got angry at the people who were happy at the news. "Show some respect," tweeted one. "Celebrating someone's death is a bit sick," said another. "Today someone's mum died," was a third.

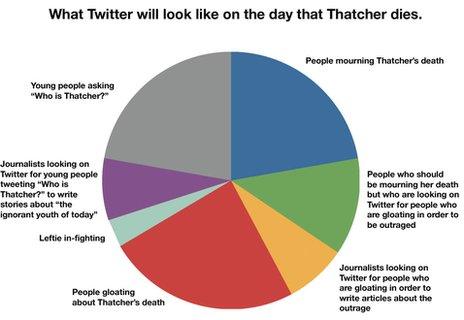

To its critics, the reaction was a microcosm of everything that's wrong with Twitter. Many retweeted and Facebooked a pie chart journalist Martin Belam had circulated in December, external entitled "What Twitter will look like on the day that Thatcher dies".

It showed an equal split between "people mourning Thatcher's death" and "people gloating about Thatcher's death". The same proportion was "Young people asking 'Who is Thatcher?'", while sections were also reserved for "People who should be mourning her death but who are looking on Twitter for people who are gloating in order to be outraged" and journalists looking on Twitter for both to write stories about them.

Martin Belam's pie chart predicted Twitter reaction

So many people took to comments on online newspaper articles that one editor, the Daily Telegraph's Tony Gallagher tweeted, external: "We have closed comments on every #Thatcher story today - even our address to email tributes is filled with abuse."

Then there was the music on YouTube. Social media drove people to songs such as Tramp the Dirt Down, Morrissey's Margaret on the Guillotine and Sinead O'Connor's Black Boys On Mopeds.

The comments sections on the YouTube videos saw the same debates flare up about speaking ill of the dead.

Twitter is the perfect vehicle to express rage, or people's outrage at other people's rage, and nothing stirs tweeters more than "very polarising personalities", according to Paul Armstrong, a social media consultant at Digital Orange.

"When it comes to well-known figures, especially controversial figures, everyone feels they can weigh in and have a personal opinion," he says.

With death, there is also a phenomenon, particularly on Twitter, of people wanting to be the first to report it, he says.

Of course, Margaret Thatcher's death wasn't the first to spark a Twitter frenzy. Michael Jackson's death was "stratospheric" and Amy Winehouse was huge too, Armstrong says. What was unusual in Lady Thatcher's case was the vitriol.

But away from the overt loving or loathing, one word dominated tweets. It was "whatever", used as a qualifier.

Thousands of tweets opened or finished with constructions along the lines of "whatever you thought of her…" or "whatever her politics".

This pronounced nod to neutrality was odd in the context of messages in tribute, acting as a curious acknowledgement of her divisiveness as a leader.

Labour tweeters urged party members to be respectful.

"Whatever you think of her she will remain a political giant. End of an era," was David Lammy's tweet, external. "Margaret Thatcher achieved something unique First (and only so far) woman PM. Today should be about respect. Let's debate her legacy later," tweeted Mike Gapes, external.

There were even Conservative MPs who used the "whatever" qualifier.

"Whatever people thought of her the changes she made were never reversed. Very sad day. Sympathy to her family," Alun Cairns MP tweeted, external.

Others seemed keen to avoid passing judgement, focusing instead on the family's loss, or preferring perhaps to bide their time.

"I send my deep condolences to Lady Thatcher's family, in particular Mark and Carol Thatcher," was Labour leader Ed Miliband's tweet, external.

"I know how I felt when I lost my mum. Condolences to the Thatcher family especially Carol & Mark on this difficult day for them," tweeted shadow transport secretary Maria Eagle, external.

Some people staged parties after the announcement - and were subsequently criticised

There's still a taboo over speaking ill of the dead, but some people choose to ignore it.

"Obviously because Margaret Thatcher's a political figure, and she was an important person, she is going to stir up emotions," says etiquette expert Jean Broke-Smith.

"But if people are politically anti her, I hope they will be kind enough to say they didn't agree with her, but they respect what she did. Now is not the time to churn up silliness or bring up bad points - it's good etiquette to let her rest and focus on her good points," she says.

Steve Chalke, a Baptist minister who has conducted many funeral services, agrees respect is important.

"A mature democracy and society is one that respects everyone's contribution and political and social debate. No-one needs to say poll tax was a great idea, and Margaret Thatcher is not my politics, but she was the leader of the country," he says.

He says often people only say good things about a person when they are dead, in eulogies.

Bob Chaundy, former obituaries editor at BBC News, says there used to be a convention in obits, particularly in print, that you didn't speak ill of the dead, but that went by the wayside by the 1980s.

However he says historically some papers were still famous for playing things down.

"It's gone out of fashion a bit now, but euphemisms used to be an obit tool to soften the blow. The Telegraph, in particular, became famous for them - a crashing bore was a 'tireless raconteur', an old windbag, 'relished the cadences of English language'," he says.

Even now, he believes broadcast obits, which go out straight away, tend to play it safer than print obits, which go out a day later and are more likely to look at the pros and cons of a person's character.

In many ways, Twitter has been a game changer.

"It's very easy to make caustic remarks in a few words, instantaneously. So for some people there's a great temptation to be direct and lack sensitivity.

"But wise commentators will always take a nuanced view of someone's death," he says. The point is Twitter doesn't only host wise commentators.

The British Library has just started archiving all UK websites.

The unique reaction to her death will be preserved.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external