Afghanistan, the drug addiction capital

- Published

Afghanistan produces 90% of all opiate drugs in the world, but until recently was not a major consumer. Now, out of a population of 35 million, more than a million are addicted to drugs - proportionately the highest figure in the world.

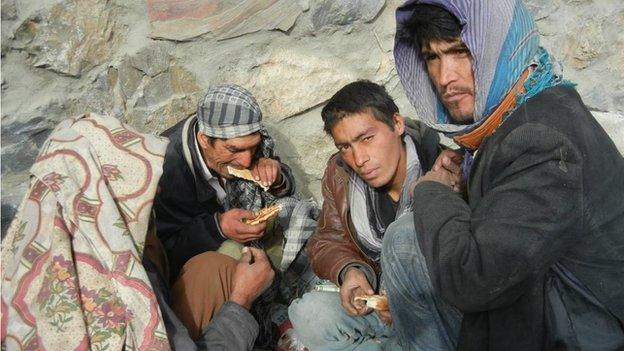

Right in the heart of Kabul, on the stony banks of the Kabul River, drug addicts gather to buy and use heroin. It's a place of misery and degradation.

In broad daylight about a dozen men and teenage boys sit huddled in pairs smoking and injecting. Among them are some educated people - a doctor, an engineer and an interpreter.

Tariq Sulaiman, from Najat, a local addiction charity, comes here regularly to try to persuade addicts to get treatment.

"We are already losing our children to suicide attacks, rocket and bomb attacks," he says. "But now addiction is another sort of terrorism which is killing our countrymen."

At the age of 18, Jawid, originally from Badakhshan in the north of Afghanistan, has already been hooked on heroin for 10 years. His uncle introduced him to drugs when he was a small child, to make him work harder on the land.

"I hate my life. Everyone hates me. I should have been at school at this age, but I am a junkie," he says.

His father is dead. His disabled mother worries about her son constantly. All she wants from life is for him to get clean, but she begs on the streets to pay for his daily dose to prevent him stealing.

"I always tell Jawid if I die, he will end up sleeping under the bridge with other addicts," she says.

This is the fate of the most hardcore addicts, whose fires can be seen at night. Police regularly beat and disperse them, and sometimes throw them in the river.

Jawid: ''I came here to quit, to become a nice person''

The reasons why so many Afghans are turning to drugs are complex. It's clear that decades of violence have played a part.

Many of those who fled during the violence of the last 30 years took refuge in Iran and Pakistan, where addiction rates have long been high. They're now returning and bringing their drug problems with them, officials say.

Unemployment - which currently stands at nearly 40% - is also taking its toll.

"If I had a job, I wouldn't be here," says Farooq, one of the addicts by the river, who has a degree in medicine and once worked as a hospital manager.

He says he takes drugs "to be calm and to relax" - but that he would prefer to be dead than a junkie, as he now is.

Another factor is the increasing availability of heroin, which over the last decade has begun to be refined from raw opium in Afghanistan itself.

To buy heroin in Kabul is "as easy as buying yourself something to eat", addicts say. One gram costs about $6 (£3.91), and it's available in every corner of the city.

"Traditionally, what we tend to argue is that the demand causes the supply," says Jean-Luc Lemahieu, regional representative of the UN drugs agency UNODC - one of the few organisations working on drug eradication in Afghanistan.

"What we have forgotten, though, is that… the sheer appearance of that product on the market causes a local demand."

When foreign troops arrived in Afghanistan in 2001, one of their goals was to stem drug production. Instead, they have concentrated on fighting insurgents, and have often been accused of turning a blind eye to the poppy fields.

Opium has been around in Afghanistan for centuries, used as a kind of medical cure-all.

In a hospital in the northern city of Mazar-e Sharif, I met an Afghan woman, Fatima, who had taken opium while suffering from bleeding after childbirth, because it was cheaper than going to a doctor.

Then she gave it to her baby to stop her coughing during breastfeeding - and now both are addicted.

Women and children account for 40% of the country's drug addicts.

While Fatima and her baby are getting treatment at a public hospital, few Afghan addicts get any help at all.

All told, the health ministry runs 95 addiction treatment centres around the country, with enough bed space for 2,305 people.

Its entire budget for treating the country's one million drug addicts is just $2.2m (£1.4m) per annum - a little over $2 per addict, per year.

Jawid alone consumes heroin worth about three times that every day.

While I was in Kabul, he got a place at the centre run by Tariq Sulaiman's Najat charity. The treatment consists of going "cold turkey" for 72 hours.

The participants began by getting their heads shaved. After one day, Jawid was in pain, but he could deal with it. Then, on the second night, he started shouting and crying and banging his head against a wall.

When I met him on the street, he denied that he was back on heroin, but his glazed eyes and rambling speech told a different story.

As he disappeared into the snowy twilight, his chances of kicking his habit seemed bleak.

And as Afghanistan faces so many problems on so many fronts, its chances of winning the wider war on drugs seem equally uncertain.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external