A Point of View: Science, magic, and madness

- Published

Galileo was a great scientist partly because he wasn't afraid to admit when he was wrong, argues Adam Gopnik, who only wishes some of the people who write to him could do the same.

When you write for a living, over time you learn that certain subjects will get set responses. You're resigned to getting the responses before you write the story.

If you write something about Shakespeare, you will get many letters and emails from what we call the cracked (and I think you call the barking), explaining that Shakespeare didn't write the plays that everyone who was alive when he was, said he had.

If you write something about the scandal of American prisons, you will be sent letters, many heartbreaking, from those wrongly imprisoned - and you will also get many letters from those who you're pretty sure couldn't possibly be more rightfully imprisoned. Sorting out what to say to each kind is a big job. (My wife has a simple rule - be nice to the ones who are going to be getting out).

The oddest response, though, is if you write making an obvious point about an historical period or historical figure, you will get lots of letters and emails insisting that the obvious thing about the guy or his time is completely wrong.

If you write about Botticelli as a painter of the Italian Renaissance, you'll be told sapiently that there was never really a renaissance in Italy for him to paint in. If you write about Abraham Lincoln and emancipation, you'll be bombarded, on a Fort Sumter scale, with people telling you that the American Civil War wasn't really fought over slavery. The Spanish Inquisition was a benevolent, fact-checking organisation, Edmund Burke was no conservative… On and on it goes.

Now these letters and emails come more often from the half-bright, some of them professional academics, than from the fully bonkers or barking.

You can tell the half-bright from the barking because the barking don't know how little they know, while the half-bright know enough to think that they know a lot, but don't know enough to know what part of what they know is actually worth knowing.

Not long ago, for instance, I wrote an essay about the great Galileo, external, and the beginnings of modern science. I explained, or tried to, that what made Galileo's work science, properly so-called, wasn't that he was always right about the universe (he was very often wrong) but that he believed in searching for ways of finding out what was right by figuring out what would happen in the world if he wasn't.

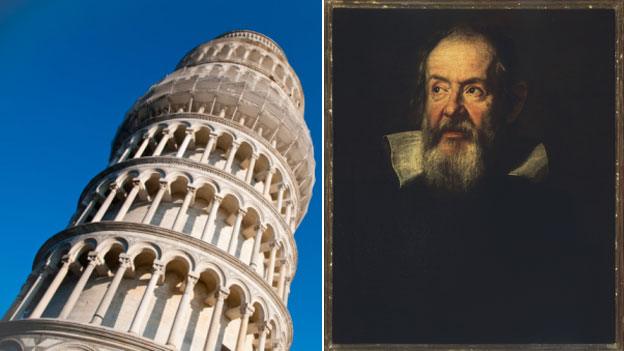

One story of that search is famous. When he wanted to find out if Aristotle was wrong to say that a small body would fall at a different speed from a large body, he didn't look the answer up in an old book about falling objects. Instead, he threw cannonballs of two different sizes off the Tower of Pisa, and, checking to make sure that no-one was down there, watched what happened. They hit the ground at the same time.

That story may be a legend - though it was first told by someone who knew him well - but it's a legend that points towards a truth.

We know for certain that he attempted lots of adventures in looking that were just as decisive. He looked at stars and planets and the way cannonballs fell on moving ships - and changed the mind of man as he did. We call it the experimental method, and if science had an essence, that would be it.

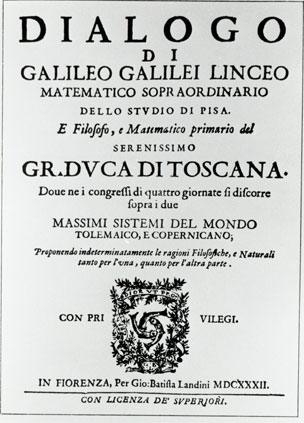

In 1632 Galileo wrote a great book - his Dialogue On Two World Systems. It's one of the best books ever written because it's essentially a record of a temperament, of a kind of impatience and irritability that leads men to drop things from towers and see what happens when they fall.

He invented a dumb character for the book named Simplicio and two smart ones to argue with him. The joke is that Simplicio is the most erudite of the three - the dumb guy who thinks he's the smart guy (the original half-bright guy), who's read a lot but just repeats whatever Aristotle says. He's erudite and ignorant.

Galileo wasn't naive about experiments. He always emphasises the importance of looking for yourself. But he also wants to convince you that sometimes it's important not to look for yourself, not just to trust your own eyes, and that you have to work to understand the real meaning of what you're seeing.

But on every page of that wonderful book, he's trying to imagine a decisive test - dropping a cannonball from a ship's mast, or digging a hole in the ground and watching the Moon - to help you argue your way around the universe.

There's a lovely moment, it could be the motto of the scientific revolution, when Salviati, one of his alter egos, says, "Therefore Simplicio, come either with arguments and demonstrations and bring us no more Texts and authorities, for our disputes are about the Sensible World, and not one of Paper."

Galileo's Dialogue On Two World Systems

In that essay I wrote about Galileo I compared him to John Dee, the famous English magician, alchemist and astrologer, who was one of his contemporaries who was also a consultant to Queen Elizabeth I, and who read everything there was to read in his time and knew everything there was to know in the esoterica of his time - but didn't know what was worth knowing.

He knew a lot about Copernicus, for instance, but he also spent half his life trying to talk to angels and have demons intervene to help him turn lead into gold.

Well, it turns out that John Dee the magician and astrologer has his admirers - indeed his web pages and his fan clubs and his chatboard, just like Harry or Liam or Justin - and they took up the cause of the old alchemist with me. How dare you knock John, his fans, some of them half-bright, some of them just a little, well, barking, insisted. Wasn't he a formidably erudite man particularly on just those subjects - stars and orbits and falling objects - that Galileo cared about too? Why shut him out of the scientific creed.

Well, that was the point I was making. And it seems to me worth making again - and then again and then again. It just can't be made too often.

The scientific revolution wasn't an extension in erudition. It involved instead what we might call a second-order attitude to erudition - and if that sounds fancy, it just means the human practice of calling bull on an idea which you think is full of it, and being unafraid to do so.

Dee was a learned man - too learned a man, in fact, in whose head all kinds of stuff lodged, some obviously silly and some in retrospect sane, but impacted together like trash in a dump heap. Above all, his work is filled with supernatural explanations - with angels and demons and astrological spells.

Galileo, emphatically did not believe in magic. Galileo has no time for supernatural explanations of any kind - indeed, when he goes wrong, as he did when he rejected the idea that the Moon causes the tides, it's because he resists the right explanation because it just sounds too strange or magical.

John Dee believes in some things that now belong to science - but in a hundred others that don't. And not once in his life did he ever seem to ask the essential question - is this idea bull or is it for real?

The smartest people of his time knew the score. Ben Jonson wrote his play, The Alchemist, about someone just like Dee. And he called his alchemist Subtle, exactly to make the point that you could be very subtle and very silly all at the same time.

History has taught us that science didn't just happen in a burst. Alchemy and astrology evolved slowly and over time into chemistry and astronomy. Galileo even made a buck in his youth by casting horoscopes for rich people.

There were no bright lines. Indeed sometimes science slipped back into astrology and alchemy and superstition and the occult. It's well-known that Isaac Newton spent a lifetime searching for the Philosopher's Stone.

But science never slipped all the way back. This new habit of throwing things off towers to see how fast they really fell, this experimental method, made sure that it couldn't. Truth no longer depended on the prestige, or the intelligence or even the integrity of any one person. That's why Galileo had the last laugh on the inquisitors.

Well, why does any of this matter except to historians and the barking, or half-bright?

An Alchemist in His Study by Egbert van Heemskerk I (1610-1680)

It matters because every time we make science more esoteric than it really is, we make modern life - which depends on science - more complicated than it needs to be.

The glory of modern science is that, while only a very few can understand its particular theories, anyone can understand its peculiar approach - it is simply the perpetual assertion of experience over authority, and of debate over dogma.

When we insist, as all the wisest child psychologists do now, that every child is like a small scientist, we don't mean that she has esoteric knowledge of a broad range of subjects, or talks to angels, or makes lead into gold.

We mean that she makes a theory about how her blocks are going to fall down and then tests it by knocking them over. And her range of knowledge in that way grows by leaps and bounds.

Science is really just that child's groping, with wings on - no, not with wings on, rather up on stilts, awkward-looking earthbound instruments, that get you high enough to see the world.

There's supposed to be a sign up on the Tower Of Pisa: "Please don't throw things from this tower". That sign is the best memorial that Galileo could ever have.

Of course, I'm not sure that it's actually there. I'll have to go and look.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external