Viewpoint: Margaret Thatcher funeral's place in history

- Published

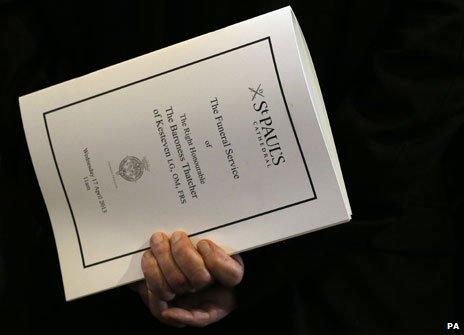

The funeral of Margaret Thatcher, which passed off far more harmoniously than many people had predicted, was an occasion rich in ironies, writes Dominic Sandbrook.

The grocer's daughter, feted by her admirers as the heir to the great commoners of the past, made her last journey in an atmosphere of regal splendour.

She never fought in battle, yet her funeral was nothing if not a military spectacle. She saw herself as the champion of Middle England, yet her granddaughter Amanda Thatcher read the first lesson in an American accent.

And most striking of all, the whole thing passed off with surprisingly little rancour or discord. To judge by much of the newspaper coverage over the last week or so, Margaret Thatcher divided the nation more than any other figure in our recent history.

And yet most of the crowds lining the streets, 10 or 12 deep in places, came to applaud or bow their heads. After all the predictions of protest and disorder, the prevailing note was one of respect and appreciation.

Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about the funeral, though, was that it happened at all. Most prime ministers have had rather quieter send-offs.

As many of the Iron Lady's critics pointed out, her chief rival for the title of Britain's most influential post-war leader, Labour's Clement Attlee, had a remarkably quiet funeral when he died in 1967.

Although Attlee had served in World War I, was badly wounded in the Mesopotamian campaign and was Churchill's deputy throughout the long struggle against Nazi Germany, his funeral had none of the military trappings that we saw yesterday.

Instead, barely 150 people paid their respects at Temple Church in Westminster, while the crowds outside were just 30-strong. The next day's papers reported the event on the inside pages, if at all. And the television cameras were nowhere to be seen.

A more obvious comparison, of course, is with Sir Winston Churchill's state funeral, which had taken place two years earlier. Indeed, I rather suspect that Churchill's funeral was at the back of Lady Thatcher's mind when she considered the arrangements for her own send-off, not least because Churchill was one of her great heroes.

Churchill's coffin travelled up Ludgate Hill to St Paul's, as did hers, accompanied by a military band. His funeral was attended by the Queen, as was hers. And yesterday was the first time since that cold day at the end of January 1965 that the bells of Big Ben had fallen silent as a mark of respect for the dead - with the exception of a brief period in the 1970s, when the tower was closed for repairs.

The precedent of Churchill's funeral sheds some light on the extraordinary sense of mission that drove Margaret Thatcher's political career. It took place against the backdrop of the supposedly swinging Sixties - among the records in the Top Ten that week were hits by the Supremes, the Kinks, Sandie Shaw and Cilla Black. Yet many onlookers felt that the funeral marked the definitive passing of British greatness.

Looking around him inside St Paul's that day, the Labour minister Richard Crossman reflected on "what a faded, declining establishment surrounded me". Churchill's funeral, he wrote in his diary, "felt like the end of an epoch, possibly even the end of a nation". And in the Observer, Patrick O'Donovan was convinced that "this was the last time such a thing could happen. This marked the final act in Britain's greatness. This was a great gesture of self-pity and after this the coldness of reality and the status of Scandinavia".

These were precisely the assumptions that Margaret Thatcher was determined to reverse. "I can't bear Britain in decline," she famously told the BBC shortly before she became prime minister in 1979. "I just can't. We who either defeated or rescued half Europe, who kept half Europe free when otherwise it would have been in chains!"

Whether you agree with her diagnosis of decline, of course, is up to you - and as the last week has shown, there is still astonishingly fierce disagreement about her remedies. Even so, I doubt that many of the guests at yesterday's funeral would have echoed Crossman's thoughts about the death of a nation, let alone O'Donovan's pessimism at Britain's prospects. It is true that George Osborne felt moved to tears, but I don't think he was contemplating Britain's finances at the time. At least, I hope not.

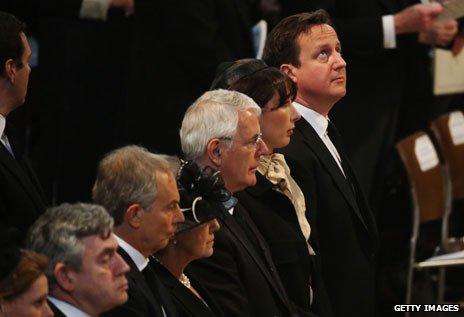

There was a marked military involvement in the ceremony

In an odd way, therefore, Lady Thatcher's funeral felt a more comfortable occasion than Churchill's. Back in 1965, the pageantry looked like the last relic of a dying imperial order, ill-fitting and anachronistic in the age of the jet aeroplane. In Crossman's words, Churchill's funeral was attended by "aged marshals, grey, dreary ladies, decadent Marlboroughs and Churchills".

By comparison, Lady Thatcher's guest list was more eclectic, with Jeremy Clarkson and Katherine Jenkins joining Henry Kissinger, Dick Cheney and Lech Walesa in the cathedral. There was, of course, plenty of mildly baffling flummery, and I particularly enjoyed seeing the Lord Mayor of London's mourning sword, carried aloft before the Queen and Prince Philip as they walked into St Paul's.

There were protests over the nature and cost of the funeral

But watching the funeral procession wending its way along the Strand, I was struck above all by the contrast between the shabby, declining London that buried Churchill and its brash, Technicolor modern-day equivalent. At one moment, the television cameras framed Lady Thatcher's funeral cortege against a lurid hoarding for a London wine bar. And in its way, that image spoke volumes about her legacy.

At any funeral, though, your thoughts inevitably come back to the individual humanity of the deceased. The vast crowds came to mourn an icon. Those who knew Lady Thatcher best, however, had come to say farewell to a woman, a human being of flesh and blood who was not, perhaps, as different from the rest of us as her critics and champions often suggest.

Four prime ministers attended the funeral

In his sermon, the Bishop of London, Richard Chartres, quoted a revealing letter that Margaret Thatcher sent to a little boy in 1980, external, a year into her extraordinary premiership. "Last night when we were saying prayers, my daddy said everyone has done wrong things except Jesus," the nine-year-old had written. "I said I don't think you have done bad things because you are the prime minister. Am I right or is my daddy?"

Given that the British economy was then lurching deep into recession, her critics were gathering and her very political survival seemed unlikely, the astonishing thing is that Mrs Thatcher replied at all. That she did so in her own handwriting is even more remarkable, and a useful reminder, on the day she was laid to rest, of the complicated human being behind the political caricatures.

"However good we try to be, we can never be as kind, gentle and wise as Jesus," she wrote. "There will be times when we do or say something we wish we hadn't done and we shall be sorry and try not to do it again."

As prime minister, she added, she tried "very hard to do things right". But even the Iron Lady, the ultimate conviction politician, had to admit: "We can never be perfect."

On that, if on nothing else, I assume her admirers and her detractors would agree.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external