A life lived in tiny flats

- Published

The UK has some of the smallest new homes in Europe. So how can people cope living in a small space?

Small is beautiful. But not if you have to live in it, a studio flat dweller might respond.

The UK has a housing crisis. A shortage of homes has pushed prices out of the reach of many hoping to get onto the ladder. But once they get there, they may be disappointed - the UK has some of the smallest properties in Europe.

Research from the Royal Institute of British Architects, external (Riba) says that lack of space is the most common cause of dissatisfaction people cite in relation to their homes. Almost half of people surveyed (47%) said there wasn't enough space for furniture they owned, 57% said there was not enough storage space and 28% felt they couldn't get away from other people's noise.

There are minimum space standards for social housing, which covers council and housing association properties.

But while many people might associate London with tiny properties, the capital is the only place with minimum regulations for private new build homes.

Riba cited research showing that new homes in Ireland, Holland and Denmark were respectively found to be 15%, 53% and 80% bigger than those in the UK.

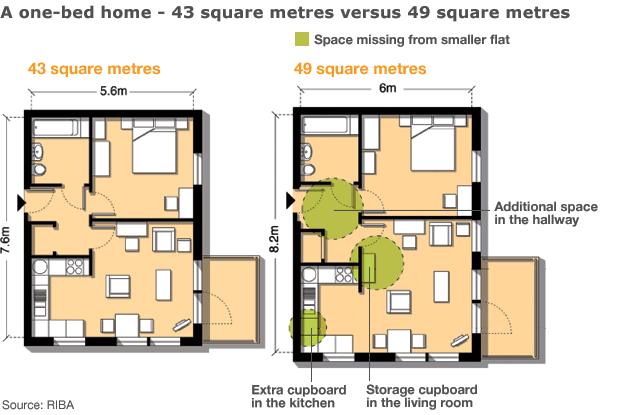

The average UK one-bedroom home is 46 sq m (495 sq ft), according to Riba. That works out at a mere 6.8m x 6.8m or 22ft by 22ft. And that's the mean average. There are plenty of people living in smaller flats.

The 46 sq m figure is 4 sq m (43 sq ft) less than the minimum standards set by London.

Riba found the average three-bedroom home is 88 sq m (947 sq ft), which is 8 sq m (86 sq ft) short of the recommended minimum.

These may sound trivial amounts but 4 sq m is equivalent to having a sofa and small computer table in your house, Riba argues. And 8 sq m is big enough for a single bedroom.

In the current drive to create more homes, Riba president Angela Brady warns against builders producing "another generation of poor quality homes without adequate space and natural light".

The UK's reputation for cramped new homes has led to what the Daily Telegraph dubbed "rabbit hutch Britain"., external

Edwin Heathcote, author of the Meaning of Home, says that the volume housebuilders "try to squeeze in" as many units as they can into urban sites.

And unlike other countries, houses in the UK are sold on the number of bedrooms rather than square footage, he says. The result is a lot of small rooms. And UK consumers like gardens, which leads to smaller houses.

The rise of solo living is another factor. People wanting to live alone trade space for having their own flat.

Housebuilders reject the criticisms and claim that minimum space standards would push up house prices. "If you specify that rooms have got to be bigger then you will drive the price up," warns Steve Turner, from the Home Builders Federation.

Happily living in a small home is first of all about psychology, says Hannah Booth, homes editor at Guardian Weekend. "You can live without much more than you think."

Apartment dwellers in New York and Japan know the secrets of this lifestyle, she says. "They're the masters, they eat out a lot, spend a lot of time in the park. In the winter your home can be a nice little cocoon."

A wide angle lens is crucial for viewing some properties

Once you've taken that on board you need to de-clutter. There's no need for book- or CD-hoarding - many younger people have realised digital devices can cover that.

Booth is in favour of beds that pull down from wardrobes that are fully made up and ready to sleep in. Wooden drop-leaf and gate-leg tables - which date back to the 16th Century - are a testament to a historic lack of space in British homes. They're still very popular now.

But while clutter is a problem, strict minimalism isn't the answer, she says. A strategically placed rug or sofa will act as dividing line between kitchen and living area. A key tip is to show as much of the floor as possible - so chair legs are better than chairs with a chunky base.

Surfaces can be creative - chopping boards on oven hobs when the cooker is not in use. Light is important to creating a spacious feel so blinds are better than curtains. And it makes sense to paint above the picture rail in another colour - it creates a sense of airiness.

There are people who relish the chance of creating a small but liveable space.

Dr Mike Page, an engineer and psychologist at the University of Hertfordshire has created a prototype with this in mind. The QB2 is 4m long, 3m wide and 3m high. Designed for two people to live in, it will be available to buy.

Instead of lots of different rooms it has one multifunctional space. "I'm a sailor and boats are designed like that," he explains.

There is an appeal to it linked to minimalism, he says. "Compact living will not appeal to everyone, but for me there is a beauty to be had in an efficient use of energy and space, a pleasure in being able to live comfortably in a sufficient space, constructed almost entirely from sustainably sourced materials."

The government's changes to housing benefit - nicknamed the "bedroom tax" by Labour - will raise questions about housing space, Heathcote argues. "Do you need spare rooms or space somewhere else?"

"The existential meaning of home hasn't changed much," he argues. "We still crave natural light, floors, doors and windows." What has altered is how we want that space divided up. He says it makes sense to prioritise shared spaces like kitchens where people now spend much of their time at home.

Heathcote is less keen on the rise of the multi-bathroom house. "There are too many bathrooms in modern houses taking space away from more important rooms.

"It's completely insane when every bedroom has en suite and then there's a family bathroom as well."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external