Escaping the train to Auschwitz

- Published

Simon Gronowski, pictured aged nine with his parents, two years before he and his mother were arrested

On 19 April 1943, a train carrying 1,631 Jews set off from a Nazi detention camp in Belgium for the gas chambers of Auschwitz. But resistance fighters stopped the train. One boy who jumped to freedom that night retains vivid memories, 70 years later.

In February 1943, 11-year-old Simon Gronowski was sitting down for breakfast with his mother and sister in their Brussels hiding place when two Gestapo agents burst in.

They were taken to the Nazis' notorious headquarters on the prestigious Avenue Louise, used as a prison for Jews and torture chamber for members of the resistance.

Today, Gronowski lives a two-minute walk from this building, where he was held for two nights without food or water.

"My parents had made a mistake - only one, but a serious one, which was… to have been born Jewish - a crime that, at the time, could only be punished by death," he says.

From there, Simon and his mother and sister were transferred to the Kazerne Dossin, a detention camp 30 miles away in Mechelen, Flanders.

Detainees were taken from Kazerne Dossin directly to the death camp

"People were randomly hit sometimes just for the crime of 'looking Jewish', so you had to keep a low profile," says Gronowski.

"For the smallest infraction, we could be beaten up and locked in a cell until we were deported. Sometimes they collectively punished the entire room of 100 of us, or make us stand in the courtyard for hours, day or night whatever the weather."

Most of the prisoners knew they would be deported but had no idea, Gronowski says, that they would be executed en masse.

On 18 April, Simon and 1,630 others, including his mother, Chana, were informed they would be deported by train the next day.

His father, Leon, had been in hospital when the Germans had raided their home a month before. His mother had quickly thought to tell them she was a widow.

His older sister Ita - born in Belgium and already 18 - had Belgian citizenship and was therefore taken in a separate convoy.

Simon, who like his parents and most of Belgium's Jewish population was stateless, remembers seeing her for the last time, crying and waving to him as they left.

"I didn't really understand what was going on and what deportation would mean. I was still in my own little world, where I was a boy scout," he says. "I thought to myself, 'Goodbye my Brussels, my Belgium, my father, my dear sister, my family and my friends'."

Conditions inside the train were atrocious.

"We were packed like a herd of cattle. We had only one bucket for 50 people. How could we use it? How could we empty it? Besides, it would have been impossible to get to it," says Gronowski.

"There was no food, no drink. There were no seats so we either sat or lay down on the floor. I was in the rear right corner of the car, with my mother. It was very dark. There was a pale gleam coming from a vent in the roof but it was stifling and there was no water to be had."

![Simon Gronowksi with a cattle wagon used in the convoys to Auschwitz [Archive: Michel van der Burg / Photo: Marc Van Roosbroeck]](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/464/mcs/media/images/67137000/jpg/_67137420_wagon.jpg)

During the making of a film, Gronowski was shown wagons used by the Nazis

Soon after leaving Mechelen, the 20th convoy was attacked by three young members of the Belgian Resistance armed with one pistol, red paper and a lantern.

They made a red light, a sign for danger ahead, forcing the train driver to brake sharply. This was the first and only time during World War II that any Nazi transport carrying Jewish deportees was stopped.

Robert Maistriau, one of the resistance members, recalled that terrifying moment later in his memoirs.

"The brakes made a hellish noise and at first I was petrified. But then I gave myself a jolt on the basis that if you have started something you should go through with it. I held my torch in my left hand and with my right, I had to busy myself with the pliers. I was very excited and it took far too long until I had cut through the wire that secured the bolts of the sliding door. I shone my torch into the carriage and pale and frightened faces stared back at me. I shouted Sortez Sortez! and then Schnell Schnell flehen Sie! Quick, Quick, get out of here!"

After a brief shooting battle between the German train guards and the three Resistance members, the train started again.

Some had escaped from the opened wagon and the mood among the remaining deportees had changed. Those who had dreamed of escape suddenly become more determined and more desperate.

An hour later, men in Simon's wagon succeeded in breaking open the door. Cool air flowed into the stifling, crowded carriage. Chana Gronowski gave her son a 100-franc note which he rolled and slid into his sock, then she pushed towards the door.

Simon was too small to reach the footrail beneath the door by himself, so his mother lowered him down by his shoulders.

"My mother held me by my shirt and my shoulders. But at first, I did not dare to jump because the train was going too fast for me," he says.

"I saw the trees go by and the train was getting faster. The air was crisp and cool and the noise was deafening. I remember feeling surprised that it could go so fast with 35 cars being towed. But then at a certain moment, I felt the train slow down. I told my mother: 'Now I can jump.' She let me go and I jumped off. First I stood there frozen, I could see the train moving slowly forward - it was this large black mass in the dark, spewing steam."

But the train slowed to a stop for a second time that night and the German guards began shooting again, this time in Simon's direction. "I wanted to go back to my mother but the Germans were coming down the track towards me. I didn't decide what to do, it was a reflex. I tumbled down a small slope and just started running for the trees."

![Simon Gronowksi at the spot where he jumped from the train [Archive: Michel van der Burg / Photo: Marc Van Roosbroeck]](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/464/mcs/media/images/67068000/jpg/_67068625_simonatspot.jpg)

Gronowski recently returned to the spot where he jumped from the train

Simon walked and ran all night, through woods and over fields.

"I was used to the woods because I'd been in the cub scouts. I hummed In the Mood to calm myself, which was a song my sister used to play on the piano," he says.

Simon wanted to get to Brussels and his father, Leon.

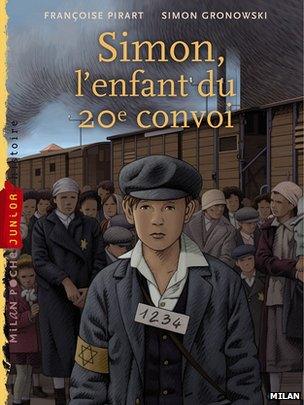

Keen for youngsters to understand his story, Gronowski co-wrote a children's book

Simon knew he risked arrest but, by dawn, he knew that he would need help. With torn, muddy clothes, he knocked on a village door and told the woman who answered that he had been playing with friends and had got lost. At the time, Belgians who failed to turn in Jews to the Gestapo would be shot and the woman took Simon to the local police officer.

For the first time, Simon was terrified. "The sight of this man in his uniform with his gun in his belt, terrorised me. I was sure he would bring me back to the Germans. He asked me what had happened and I kept telling him that I had got lost and I was playing with children and that now, I had to go to Brussels."

The policeman, Jan Aerts had guessed Simon came from the Auschwitz convoy. The bodies of three escapees were lying in the police station at that very moment. However, Aerts had no intention of betraying Simon. His wife fed him and gave him clean clothes.

Aerts arranged for Simon to catch a train back to Brussels where he arrived that evening. Simon was reunited that night with his father, a shopkeeper, although they spent the remaining years of the war hidden separately by Catholic families.

Chana Gronowski was sent to the gas chambers on arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Simon's sister Ita, 18, arrived in Auschwitz on the next but one convoy, and also died there.

In all, 25,483 Jews and 351 Roma were deported from Kazerne Dossin. Of the 233 people who attempted to escape from the 20th convoy with Simon Gronowski, 26 were shot that night, 89 were recaptured and 118 got away.

The 20th convoy was unique in that there was an attempt to rescue the deportees. It was unique in being the only convoy from which there was what could be called a mass breakout. According to some sources, it was also unique in that although 70% of the women and girls were killed in the gas chambers immediately on arrival, the remaining women were sent to Block X of Birkenau for medical experimentation.

As for the three young Belgian Resistance members who stopped the train, Youra Livschitz was captured later and executed. Jean Franklemon was arrested soon after and sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where he was freed in May 1945. He died in 1977. Robert Maistriau was arrested in March 1944. He was liberated from Bergen-Belsen in 1945 and lived until 2008.

Jan Aerts was declared a "Righteous Gentile" by the Yad Vashem museum in Jerusalem. Leon Gronowski died within months of the end of the war.

Simon Gronowski paid his way through university. He chose to be a lawyer because, he says, the Nazis had tried to dispossess and demean him, and he saw the law as the best way of countering that. Today he lives in Brussels and still practises law. He has children and grandchildren. He plays jazz.

For more than 50 years he hardly spoke about his past but Maxime Steinberg, a Belgian historian and specialist in the persecution of Jews in Belgium, persuaded him to write a book.

He now also speaks regularly in schools.

"I speak about what happened to me so that you will protect freedom in your country," he explains to children.

"I want you to know that the most important words are 'peace' and 'friendship'. I speak to bear witness, to combat anti-Semitism, all forms of discrimination and Holocaust denial; to honour the dead and the heroes who saved my life - Jan Aerts, who risked certain death in protecting me, the Catholic families who hid me during the war, and my mother, the first of my heroes."

Simon Gronowski's story, and those of many others, is also told in the new Kazerne Dossin Museum and Documentation Centre of the Holocaust and Human Rights, which opened in December.

Built facing the actual transit centre - now an apartment block - the museum cost 25 million euros and was financed by the Flemish government. Its archives include 1,200 photos of the people on the 20th convoy.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external